Scope of Work – Hussain Varawalla

Healthcare Facility Planner

ARCHITECTURAL PROGRAMMING

The architectural space program consists of a list of the number and type of hospital beds proposed, and the different types of hospital departments further broken down into individual rooms with their areas and numbers.

At the end of the list of rooms in each department, there is a conversion factor, varying from 20 to 35 per cent, to account for the horizontal circulation area or area of corridors. This percentage factor is based on the major circulation corridors having a clear width of 2.40 M (8’-0”), the international norm.

At the end of the list of departments, an additional factor is used to estimate the overall size of the hospital, to account for vertical circulation areas (such as staircases and elevators) and sometimes mechanical spaces to be provided on the floor.

It should be noted that these factors do not account for unique design features such as atriums and courtyards. Ultimately, the actual design will determine the final space requirements.

It is important to always define and understand how square feet/square meters are calculated. Misunderstandings among members of the planning team can be disastrous since the gross space requirement is substantially higher than the net space requirement, because of the multiplier factors discussed above.

APPLICABLE BUILDING CODES

From the very onset of design, it is important to determine the applicable building codes, as they can substantially affect the form of the design solution and the overall cost of the project.

The municipal liaison architect should be appointed at the very beginning of the project.

It is good practice to make all hospital buildings handicapped accessible throughout, whether it is required by code or not.

CONCEPTUAL DRAWINGS

Based on discussions with the clients, we will present a series of conceptual plans for the proposed hospital, which will be sufficient to give an idea of the proposed building showing:

• block relationships of the departments showing area, shape and location within the building;

• the number of floors, the area per floor and the shape of the building;

• the location of vertical circulation elements such as elevators and staircases and the layout of the horizontal circulation routes (corridors);

• the location of the building on the site and the conceptual site planning showing roads, parking etc.;

SCHEMATIC (PRESENTATION) DRAWINGS

Based upon decisions made in the previous stage, we will prepare and present design sketches of the proposed layout of rooms within each department for the entire hospital. These will be discussed and modified as necessary. The structural system to be used will be discussed. After finalizing the room layouts, we will prepare a final set of schematic (presentation) drawings giving plans of the proposed building, showing furniture and medical equipment layouts where necessary to demonstrate sufficiency of space.

HEALTHCARE ARCHITECTURE ADVISORY SERVICES

If you should so desire, I can work in collaboration with another healthcare architect of your choice. The scope of work can be decided by discussion between the three of us.

I can, if wanted to, suggest appropriate honest and competent healthcare architects who can work in collaboration with me, for you to choose from.

I can also help you to choose an appropriate parcel of land for the site of the proposed hospital by analyzing its suitability to house the requirements of the proposed project. Speaking from experience, this can be a very cost-effective exercise. Many clients have come to me with completely unsuitable sites, sometimes bought at considerable cost, which defeats the very purpose of the whole design exercise right from the beginning. A little thought given to this aspect of the project at the onset can go a long way to making the project financially feasible and operationally efficient.

The land acquisition process, at a minimum, must involve consideration of the following factors:

1. Size of land. Make sure that the land is large enough to meet long-range growth plans – that is, a 10-year to 20-year growth plan.

2. Usable land. Determine the total acreage that can be used. The total size purchased is rarely the same as the total acres available for the actual building.

3. Zoning restrictions. Be aware of the current zoning limitations and allowances for the area.

4. Potential adjacent development. Find out what businesses and developments are planned or permissible in the adjacent spaces. Those potential developments might not be compatible to healthcare delivery.

5. Site access. Determine if the site is accessible through major roads and if it is fairly or highly visible to passers-by.

6. Services to the site. Evaluate the cost effectiveness of bringing service utilities to the site.

7. Preliminary master site plan. Prepare preliminary master site plans for each potential property. This plan ensures that all current planned facilities and their associated parking needs fit the property. Also, the potential property should have extra space for future development.

The key point to remember here is to never let the land drive the design of the facility.

“If you don’t know where you’re going, any path will take you there.”

Sioux Proverb

“Long-range planning does not deal with future decisions, but with the future of present decisions.”

Peter F. Drucker (1974)

“Intelligent people do not make important decisions on matters about which they are ignorant when additional data are easily available.”

John Kay & Mervyn King: “Radical Uncertainty: Decision –making for an unknowable future”

“In a way, I like this phase of a novel better than the actual writing of it. In the beginning, there are so many possibilities. With each detail you choose, with every word you commit yourself to, your options close down.”

John Irving: “A Widow for One Year”

“Our job is to give the client, on time and on cost, not what he wants, but what he never dreamed he wanted; and when he gets it, he recognizes it as something he wanted all the time.”

Denys Lasdun, architect

Perhaps it seems arrogant for the architect Denys Lasdun to make the above statement. But I think that we should try to see through the apparent arrogance of the statement, to the underlying truth that clients do want designers to transcend the obvious and the mundane, and to produce proposals that are exciting and stimulating as well as practical. What this means is that designing is not a search for the optimum solution to the given problem, but that it is an exploratory process. The creative designer interprets the design brief not as a specification for a solution, but as a starting point for a journey of exploration; the designer sets off to explore, to discover something new, rather than to reach somewhere already known, or to return with yet another example of the already familiar.

THE CHALLENGE OF PREDESIGN PLANNING

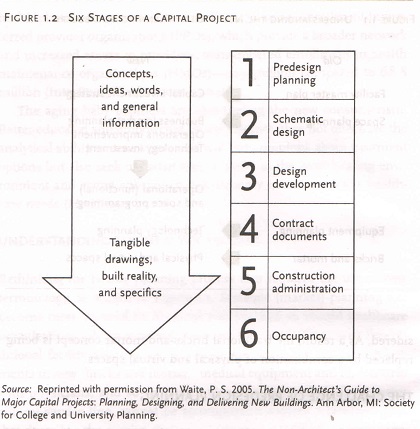

The planning and delivery of a major capital project can be divided into six stages, as shown in the figure below:

The first stage of predesign planning – the focus of this note – includes general concepts and ideas in the form of words, numbers and conceptual diagrams. Preliminary space estimates are used to develop a facility master plan and to generate project cost estimates early .Once specific projects are identified and approved, the detailed operational and space programming begins; when this is completed, the design architect can start the schematic design stage. Each subsequent phase brings more knowledge and detail about the project and has its own cast of players. Nearing the final phases, the concepts and ideas are translated into tangible architectural floor plans, drawings of construction details and the eventual reality of the three-dimensional building.

Predesign planning can be defined as the process of determining the following:

• Right services consistent with the organizations strategic initiatives, market dynamics, and business plan, at the

• Right size based on projected demand, staffing, equipment, technology, and desired amenities, in the

• Right location based on access, operational efficiency, and building suitability, with the

• Right financial structure – for example, owning leasing or partnering.

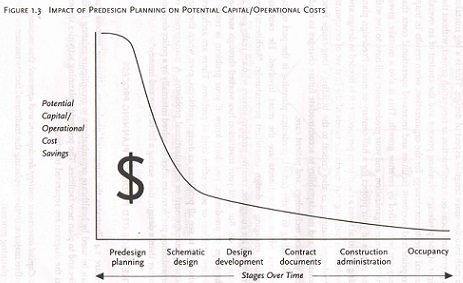

Predesign planning is the stage where the healthcare executive has the most influence on the potential success of the final project. His or her opportunity for input decreases as each subsequent stage passes. The opportunity to reduce both the initial capital cost and the ongoing operational costs is also greatest during the predesign planning stage, as shown in the figure below:

With the prospect of a new building project, healthcare executives tend to short-circuit or bypass the predesign stage to rush into the more tangible aspect of design. This is a big mistake. A premature focus on a construction or renovation project, without the rigor of a predesign planning process and the context of an overall capital investment strategy for the organization, often results in in inappropriate and overbuilt facilities and increased operational costs that may not be justified by revenue growth. This is also a mistake, given that you, your organization and your predecessors will have to live with the results of your project for half-century or more. Predesign planning is critical from a short term-term perspective: it is needed to design and construct a building that meets the needs of the first set of occupants. Predesign planning is also critical to the building’s long-range functional life and it’s adaptability to accommodate future changes in medical practice, technology, and patient care.

Predesign planning is the part of the process where non-architects are the most involved. There should be caution against engaging a design consultant prematurely. Architects and engineers are energetic, creative problem solvers who are really good at what they do. But until your institution has worked through some of the steps of predesign, you don’t know if your problem is really a design problem or some other kind of problem. There are architects who tend to see all problems as design problems, even when they’re actually management or organizational problems. A management or organizational problem can often be solved internally by a policy decision thus saving a lot of time and money.

THE INTEGRATED PREDESIGN PLANNING PROCESS

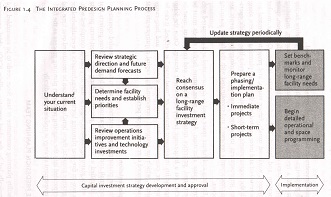

The figure below illustrates the integrated planning process that can be used by healthcare organizations to reconfigure existing facilities and to plan new facilities. The predesign planning activities shown in the diagram are separated into two:

1. Capital investment strategy development and approval: this includes five major activities (replacing the traditional facility master planning process).

2. Implementation: this includes the detailed operational and space programming for designated projects and the establishment of benchmarks to monitor long-range facility needs as the strategy is periodically updated.

Capital Investment Strategy Development and Approval

The predesign process begins with the collection of baseline data and a review of the organizations current situation, including campus access and circulation, bed utilization and configuration, space allocation and layout, and infrastructure issues. Current market dynamics, workload trends, future vision and projected demand are also reviewed and incorporated into the facility planning process, along with the organizations institution-wide and service-line specific operations improvements initiatives. Planned technology investments are currently reviewed and coordinated with the facility planning process.

Existing and future space need is documented and compared with current space allocation. At this point, future facility needs must be determined, priorities must be established, and consensus must be reached on a long-range facility investment strategy. Once the long-range facility investment, or “road map”, is defined, it can be divided or categorized into immediate, short-term and long-range projects, which are assigned corresponding capital requirements that are sequenced over a multi-year period.

Implementation

With the phasing/implementation plan in hand, detailed operational (functional) and space programming can begin for those projects that are identified as immediate priorities, along with short-term projects for which planning needs to begin so that they can be completed in a two-to-five year planning horizon. Benchmarks are established for long-range projects; these benchmarks can be monitored over time and incorporated into the ongoing predesign planning process as the facility investment strategy is updated periodically.

This note on “Predesign Planning” has been adapted from the book “Healthcare Facility Planning: Thinking Strategically” by Cynthia Hayward, and is fully endorsed by me as relevant and necessary.

I encourage you to read this very good book; it is available on Amazon.in.

The Project Launch Phase

The following are key points to remember about the project launch phase:

• Spend sufficient time defining the scope, cost, and the schedule of the project.

• Develop a budget and schedule early.

• Complete the master facility plan and operational and space programming processes before entering the design phase.

• Make smart land-acquisition decisions. Acquire sufficient land to prevent the land from driving the design, to allow for future expansion, and to accommodate future changes in healthcare delivery and technology.

• Evaluate potential joint-venture opportunities and their impact on capital and operating cost.

• Assemble the key members of the project delivery team.

The Project Delivery Team

The following are key points to remember about the selection and organization of the project delivery team.

• Select external team members – project manager, lead architect, specialty consultants, and construction manager – during the launch phase.

• Organize the Facility planning Committee first. This committee should include representatives from the board and medical staff building committees.

• Identify people from the board, from medical staff, and from the community as “project champions” and involve them in the process.

• Select members for the departmental task forces, and then involve them in the development of the master facility plan, the Operational and Space Planning (O & SP) process, and the design phase. These forces should include physicians, staff, and volunteers from various departments.

• Base selection of key external staff members on qualifications, experience with similar projects, and chemistry with internal team members.

This note on “The Project Launch Phase” and “The Project Delivery Team” has been adapted from the book “Launching a Healthcare Capital Project” by John E. Kemper, and is fully endorsed by me as relevant and necessary.