Hussain Varawalla – Healthcare Architect

Thirty-Five years of experience in the conceptualization and schematic design of medium to large health care facilities / hospitals in India.

(Completed 28/32 credits towards)Master of Architecture Kent State University, Kent, Ohio, USA

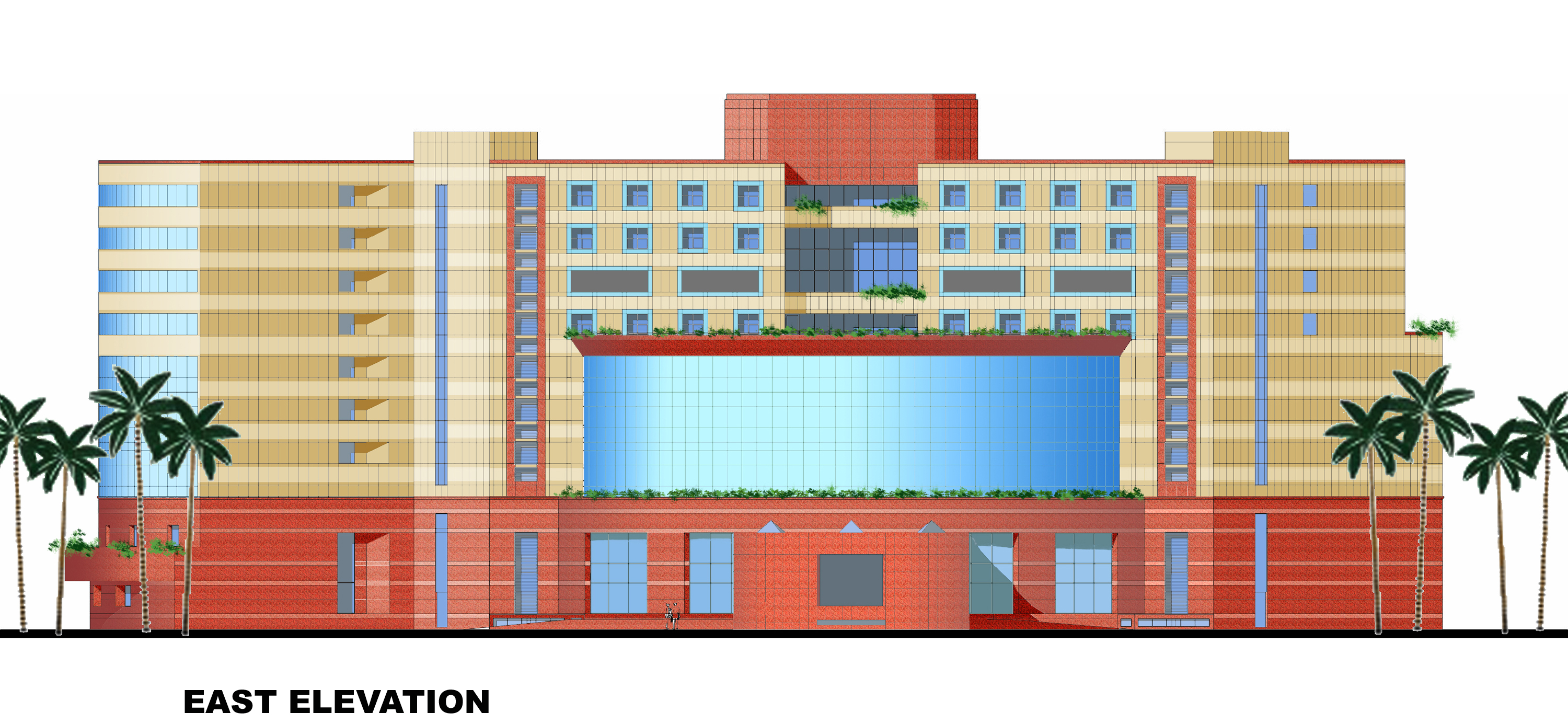

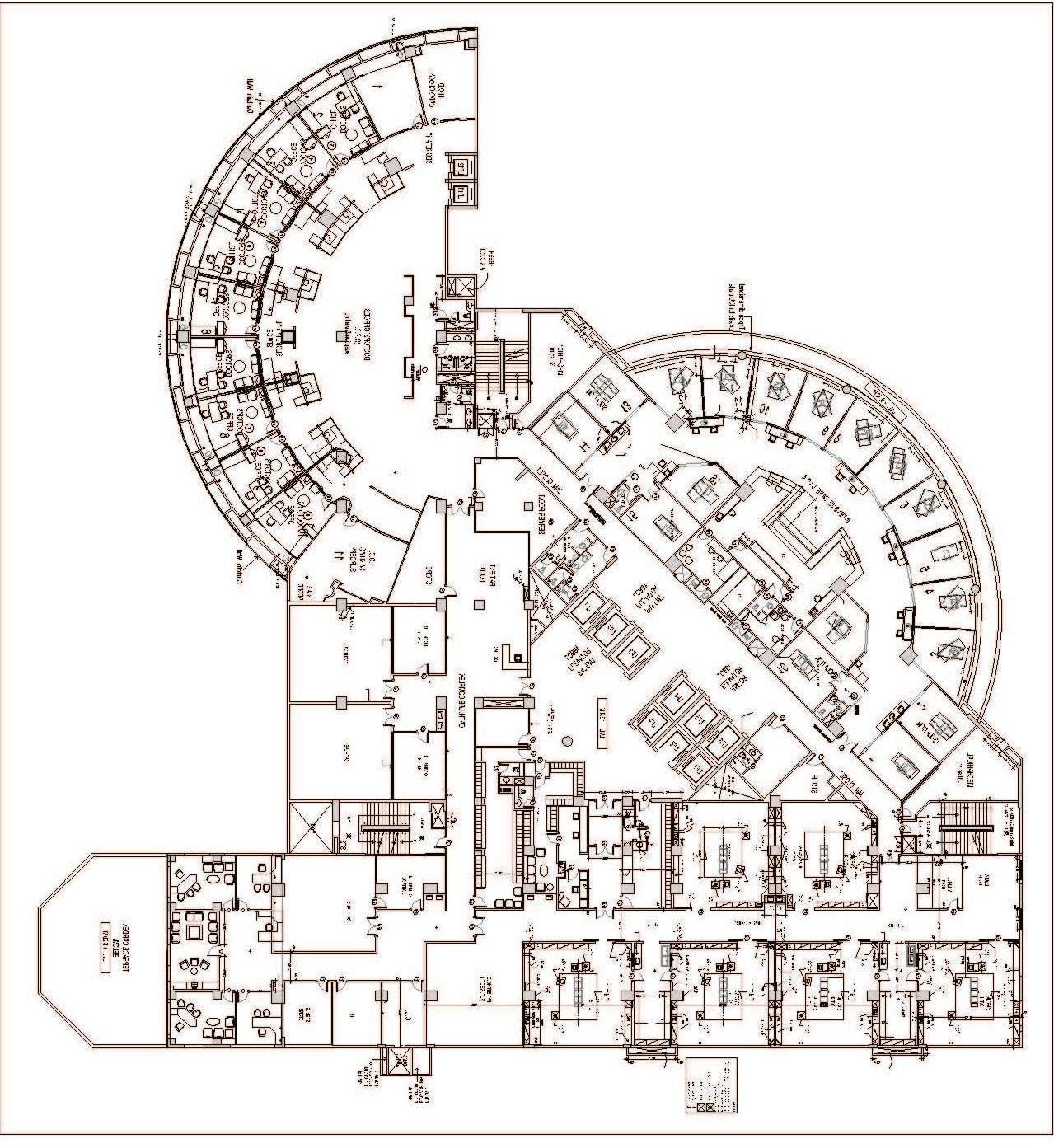

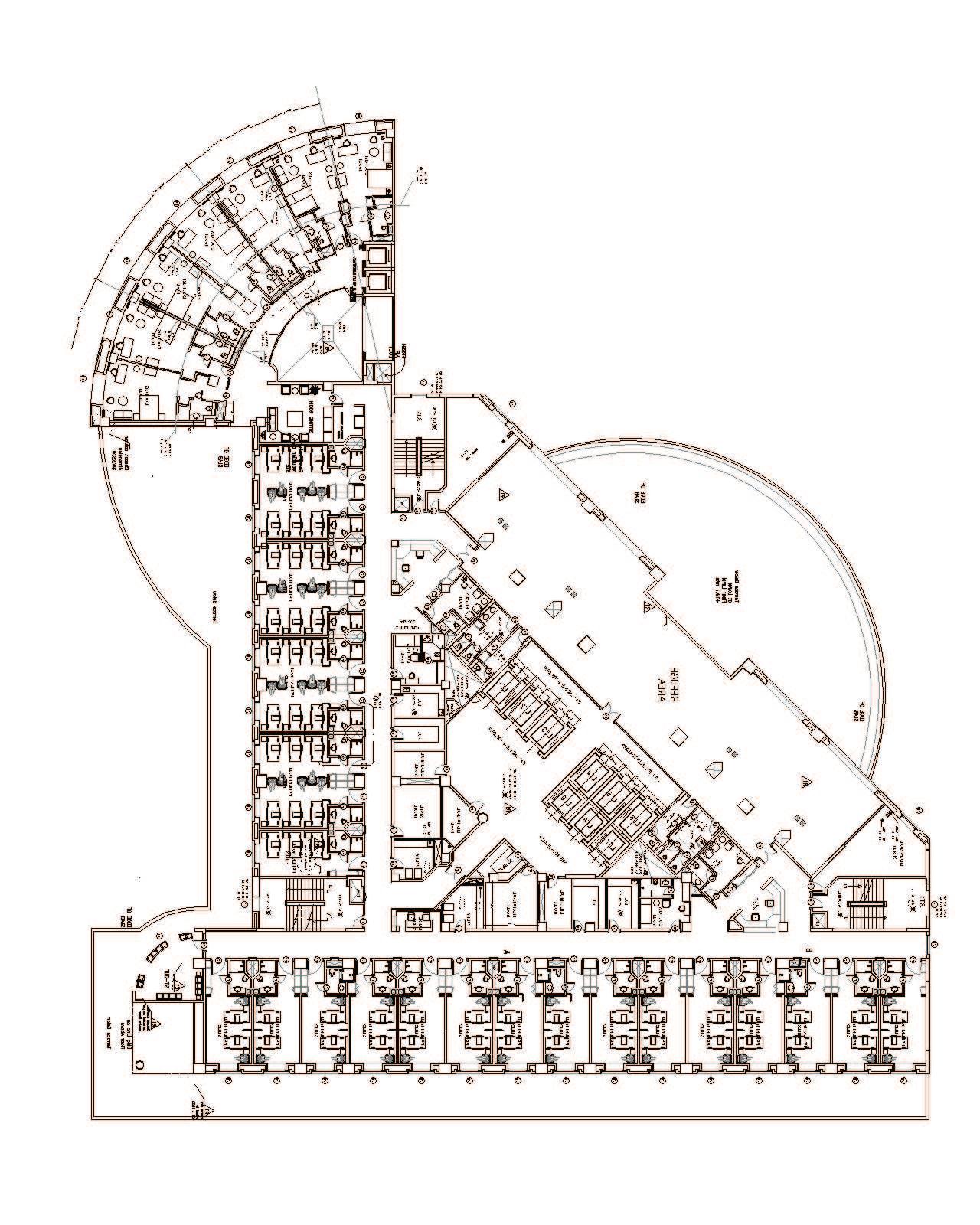

450-Bed Central Accident & Trauma System, New Delhi

Thesis project, Kent State University, Kent, Ohio -1989

Bachelor of Architecture (Hons) Indian Institute of Technology,

Kharagpur, West Bengal, India.

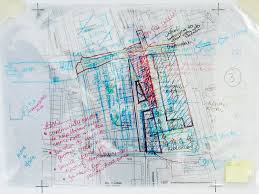

250-Bed Multi-Specialty Hospital at Mahim, Mumbai

Thesis project, Indian Institute of Technology, Kharagpur-1979

(With COVID-19 Lockdown Hair)( Me with my beloved sister and my books)

Employment Record

| Name of the Firm | Position Held | Years of Employment |

|---|---|---|

| Healthcare Architecture | Principal Consultant | Six |

| Hosmac India Private Limited | Mentor-Design Services | Three |

| Reliance Health Ventures Ltd. | Consultant-Architecture | Two |

| Hosmac India Private Limited,Mumbai | Director-Design | Ten |

| Asian Health Services, Bangalore | GM Architecture | Two |

| Indian Hospital Corporation, Chennai | Mngr.-Architecture | Two |

| HFP/Alan Ambuske, Cleveland, Ohio | Architect (USA Trainee) | One |

| Bharat Kothari & Associates, Mumbai | Architect | Four |

| Vijay Raheja & Associates, Mumbai | Architect | Five |

| Uttam C. Jain-Architect, Mumbai | Architect | Four |

| I. M. Kadri – Architect | Trainee | SixMonths |

Dedicated Healthcare Architectural Firms in Red

Did Healthcare work too in these architectural firms

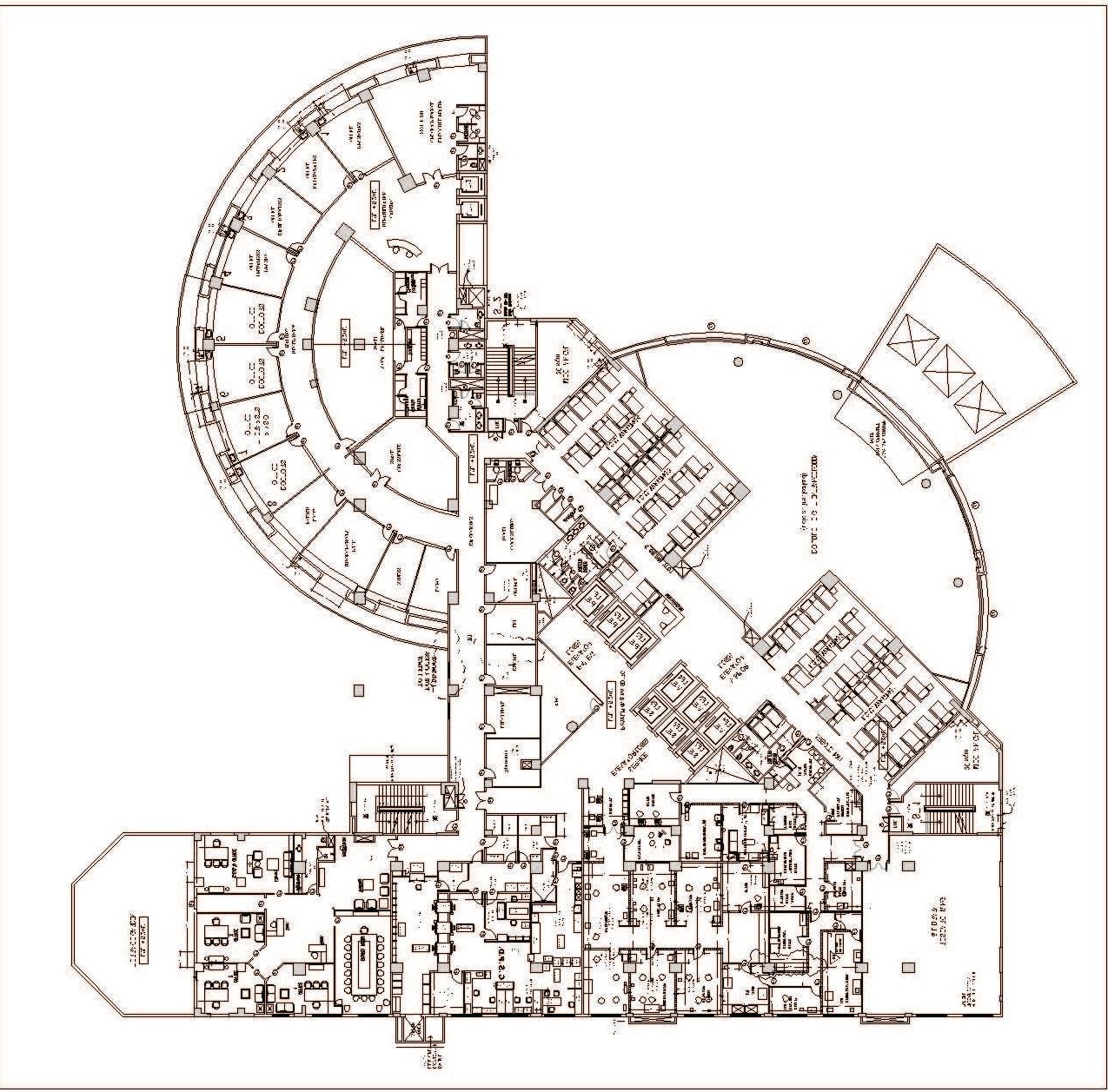

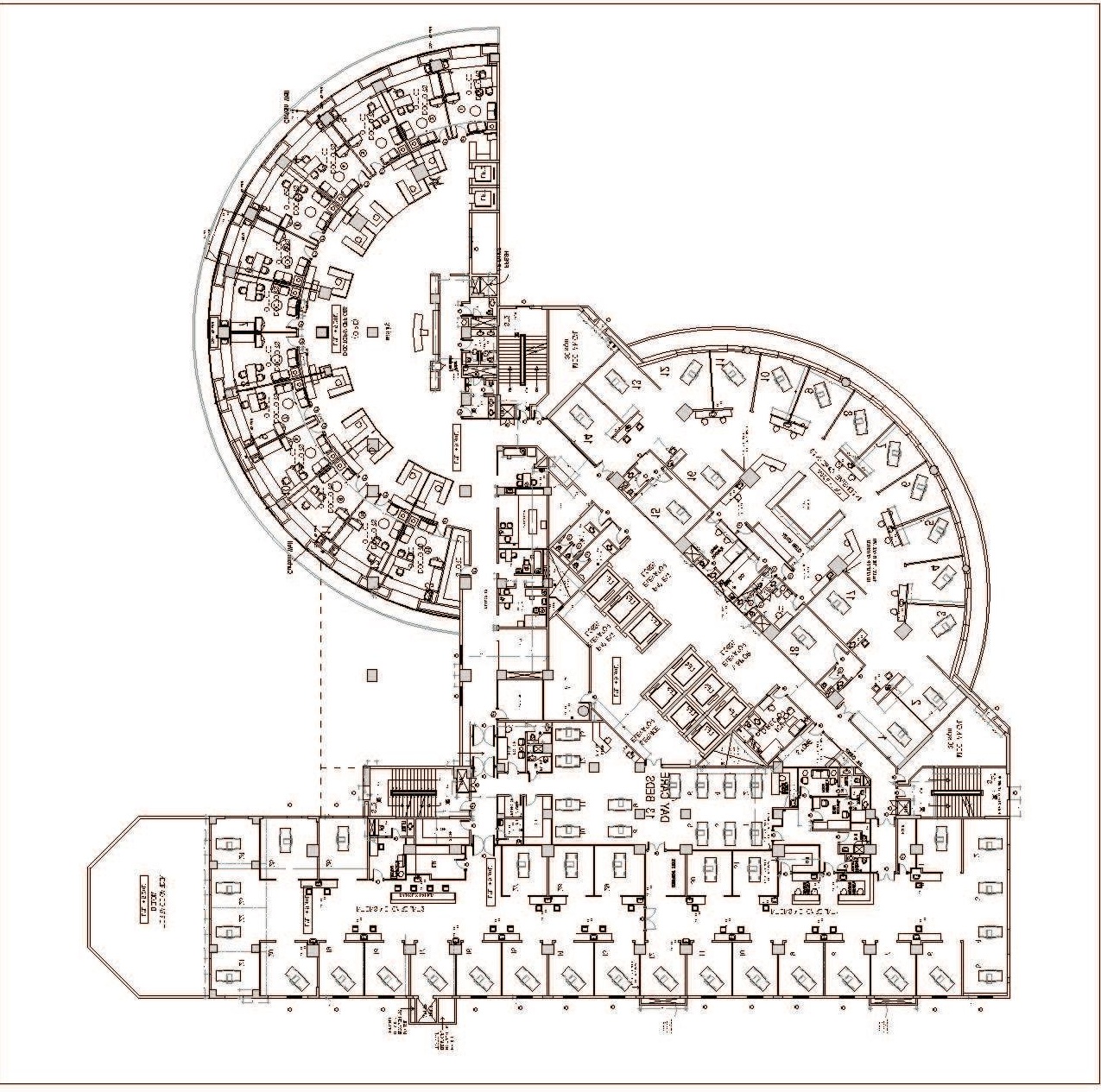

Asian Heart Institute – Bandra-Kurla Complex, Mumbai

“Mumbai’s renowned Asian Heart Institute (AHI) has been ranked by an international organisation the “safest cardiac hospital in the world” with the lowest mortality rate, a hospital official said Friday. AHI’s vice chairman and managing director Ramakant Panda said the hospital was accorded the honour among 15 hospitals in eight countries that participated in the International Cardiac Benchmarking survey conducted by the Joint Commission International (JCI). “This included data analysis of more than 6000 cardiac surgeries between October 2009-March 2011,” Panda told IANS here. The 15 JCI accredited hospitals had to provide data captured on a daily basis on the surgeries conducted and reported, set parameters to measure the quality of care provided and cooperate with verification visits by principals, said Panda, who performed heart surgery on Prime Minister Manmohan Singh nearly three years ago. “After the detailed three-year study, AHI has ranked No.1 in terms of ‘lowest complication rates’ and ‘highest survival rates’ as per the JCI survey,” he said.”I am proud to have been the designer of this outstanding hospital. What made it possible was an outstanding, visionary client.

Scope of Work – Hussain Varawalla

Healthcare Facility Planner

ARCHITECTURAL PROGRAMMING

The architectural space program consists of a list of the number and type of hospital beds proposed, and the different types of hospital departments further broken down into individual rooms with their areas and numbers.

At the end of the list of rooms in each department, there is a conversion factor, varying from 20 to 35 per cent, to account for the horizontal circulation area or area of corridors. This percentage factor is based on the major circulation corridors having a clear width of 2.40 M (8’-0”), the international norm.

At the end of the list of departments, an additional factor is used to estimate the overall size of the hospital, to account for vertical circulation areas (such as staircases and elevators) and sometimes mechanical spaces to be provided on the floor.

It should be noted that these factors do not account for unique design features such as atriums and courtyards. Ultimately, the actual design will determine the final space requirements.

It is important to always define and understand how square feet/square meters are calculated. Misunderstandings among members of the planning team can be disastrous since the gross space requirement is substantially higher than the net space requirement, because of the multiplier factors discussed above.

HEALTHCARE ARCHITECTURE ADVISORY SERVICES

If you should so desire, I can work in collaboration with another healthcare architect of your choice. The scope of work can be decided by discussion between the three of us.

I can, if wanted to, suggest appropriate honest and competent healthcare architects who can work in collaboration with me, for you to choose from.

I can also help you to choose an appropriate parcel of land for the site of the proposed hospital by analyzing its suitability to house the requirements of the proposed project. Speaking from experience, this can be a very cost-effective exercise. Many clients have come to me with completely unsuitable sites, sometimes bought at considerable cost, which defeats the very purpose of the whole design exercise right from the beginning. A little thought given to this aspect of the project at the onset can go a long way to making the project financially feasible and operationally efficient.

The land acquisition process, at a minimum, must involve consideration of the following factors:

1. Size of land. Make sure that the land is large enough to meet long-range growth plans – that is, a 10-year to 20-year growth plan.

2. Usable land. Determine the total acreage that can be used. The total size purchased is rarely the same as the total acres available for the actual building.

3. Zoning restrictions. Be aware of the current zoning limitations and allowances for the area.

4. Potential adjacent development. Find out what businesses and developments are planned or permissible in the adjacent spaces. Those potential developments might not be compatible to healthcare delivery.

5. Site access. Determine if the site is accessible through major roads and if it is fairly or highly visible to passers-by.

6. Services to the site. Evaluate the cost effectiveness of bringing service utilities to the site.

7. Preliminary master site plan. Prepare preliminary master site plans for each potential property. This plan ensures that all current planned facilities and their associated parking needs fit the property. Also, the potential property should have extra space for future development.

The key point to remember here is to never let the land drive the design of the facility.

“If you don’t know where you’re going, any path will take you there.”

Sioux Proverb

“Long-range planning does not deal with future decisions, but with the future of present decisions.”

Peter F. Drucker (1974)

“Intelligent people do not make important decisions on matters about which they are ignorant when additional data are easily available.”

John Kay & Mervyn King: “Radical Uncertainty: Decision –making for an unknowable future”

There is no single right answer or path forward, but there is one right way to frame the problem.

Clayton Christensen, Professor – Harvard Business School

These three lessons – take robustly good actions, build up options, and learn more – can help guide us in our attempts to positively influence the long term

William MacAskill – What We Owe the Future

No human purpose achieves dignity until it can be called work, and when you can experience a physical loneliness for the tools of your trade, you see that the other things – the experiments, the irrelevant vocations, the vanities you used to hold – were false to you.

Beryl Markham – West with the Night

If you want to have good ideas, you must have many ideas

Linus Pauling – Nobel Prize Winner in Chemistry, 1954

As more data becomes available and as the economy continues to change, the ability to ask the right questions will become even more vital. No matter how bright the light is, you won’t find your keys by searching under a lamppost if that’s not where you lost them. We must think hard about what it is we really value, what we want more of, and what we want less of.

Erik Brynjolfsson & Andrew McAfee – The Second Machine Age: Work, progress and prosperity in a time of brilliant technologies

“In a way, I like this phase of a novel better than the actual writing of it. In the beginning, there are so many possibilities. With each detail you choose, with every word you commit yourself to, your options close down.”

John Irving: “A Widow for One Year”

“CDS (Chief of Defence Staff) Chauhan is in regular touch with the three service chiefs to work out solutions to obstacles that they are likely to encounter in implementing this immense paradigm shift. Indeed, the armed force will have to usher in momentous changes in the way operations, logistics and application of force will be handled under theatre commands.‘The start of this journey depends on right first steps being taken towards jointness and integration,’ Gen. Chauhan has said.”

Pradip R. Sagar – Strength In Unity – India Today – August 21, 2023

Well said! The start of any journey (or project) depends on taking the right first step. If you start off in the wrong direction, you will never arrive at the right destination, no matter the amount of effort you put into it. Beginnings are very important.

“I think you learn more if you’re laughing at the same time.”

Mary-Ann Shaffer and Annie Barrows – The Guernsey Literary & Potato Peel Pie Society.

“The significant problems we face cannot be solved by the same level of thinking that created them.”

Albert Einstein

“A problem well stated is a problem half solved.”

Charles F. Kettering – American inventor

“To act only when a problem becomes obvious is to miss an important opportunity to solve the problem.”

Donella H. Meadows – Thinking in Systems

“The Earth is our Mother. She nourishes us. That which we put into the ground she returns to us.”

Big Thunder (Bedagi) Wabanaki Algonquin

“For every complex problem there is an answer that is clear, simple and wrong”

H.L.Mencken – Journalist and Essayist

“We are free to do what we want as long as it is what everyone else is doing and what our political and economic system expects us to do.”

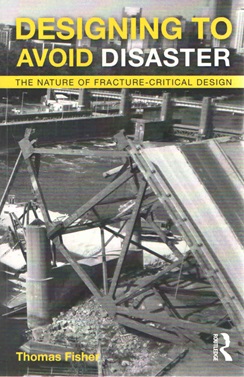

Thomas Fisher – Philosopher and Architect

“Manifest plainness, embrace simplicity, reduce selfishness, have few desires”

Lao-Tzu

“It is better to conquer yourself than to win a thousand battles”

Gautama Buddha

“The highest activity a human being can attain is learning for understanding, because to understand is to be free”

Benedict de Spinoza

“The degree of one’s emotions varies inversely with one’s knowledge of the facts”

Bertrand Russell

“The intellect of man is forced to choose

Perfection of the life, or of the work,

And if it takes the second must refuse

A heavenly mansion, raging in the dark.”

William Yeats, “The Choice”

I have seen nothing, understood nothing,

Lord, help me see, make me understand.”

Rajanikanta Sen –Bengali Poet and Composer

“Some people like to muse on the philosophical conundrum ‘What is the meaning of life?’ But more practical philosophers ask, ’How can I make my life meaningful?’ The happiest people in the world ask, ’What if I could find some way to get paid for doing what I love?’”

Michael J. Gelb – Think Like Da Vinci

“Such bribyng for the purse, which ever gapes for more,

Such hordyng up of worldly wealth, such keeping much in store…

Such falshed undercraft, and such unstedfast ways,

Was never sene within men’s hartes, as is found nowadays.”

Anonymous

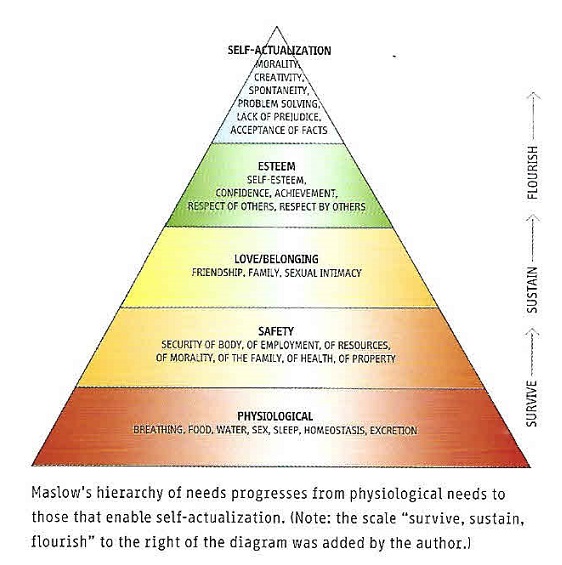

“If the only tool you have is a hammer, you tend to see every problem as a nail.”

Abraham Maslow – American psychologist

“She seemed so content and happy that I felt bound to ask: ‘So this is your Shangri-La?’

She thought about this for a bit. ‘There are many challenges here, of course,’ she said, ‘but most of them are in your mind – and if a place can help you see that, then what else is it but Shangri-La?’”

Amitav Ghosh – Wild Fictions

‘What we need to become happier and to make the world a better place is not more pious illusions but a clearer understanding of the way things are.

The mere fact that you have the leisure to read this book puts you in very rarefied company. Many people on earth at this moment can’t even imagine the freedom that you currently take for granted.”

Sam Harris – Waking Up

We have to look far in the distance when we try to put right what is wrong at the moment. We should worry about what new problems we create when we try to solve a problem…

Abdulrazak Gurnah – The Last Gift

Endure. A word as solid as a tree trunk. A good word upon which to build a life, I thought. I would learn it, and it would help me through dark times.

…I pondered the word endure, what it meant. It didn’t mean giving in. It didn’t mean being weak or accepting injustice. It meant taking the challenges thrown at us and dealing with them as intelligently as we knew until we grew stronger than them.

…the more love we distribute, the more it grows, coming back to us from unexpected sources. And its corollary: when we demand love, believing it to be our right, it shrivels, leaving only resentment behind.

…such is the paradoxical power of the mind. When we control it, it’s our best friend, but when we allow it to control us, it becomes our worst enemy.

Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni – The Forest Of Enchantment

The love of God can’t fill an empty belly and when it’s full one seldom thinks to thank Him.

On a single bush one is constantly surprised by the remarkable character shown by each individual rose. But from the house all one sees is a garden, which is all there is to it anyway in the long run.

Paul Scott – The Towers of Silence

Men are disturbed not by things, but by the view they take of them.

Epictetus – A Stoic Greek philosopher

…one of the truly bad effects of religion is that it teaches us that it is a virtue to be satisfied with not understanding.

Richard Hawkings – The God Delusion

A selfish hand has a short reach.

Hernan Diaz – Trust

I don’t believe in god…humanity is god. Humanity is the only god I know. If humanity doesn’t need something it will disappear. People who are not loved will disappear. Everything that is not loved will disappear from the face of the earth. We only exist through the love of others and that’s what it’s all about.

Peter Carey – Do You Love Me? – Collected Stories

But he would continuously change them around, according to his studies and tastes of the moment, for he considered books as rather like birds which it saddened him to see caged or motionless.

Italo Calvino – Baron In the Trees – Our Ancestors

Oh, my dear boy, one mustn’t expect gratitude. It’s a thing no one has a right to. After all, you do good because it gives you pleasure. It’s the purest form of happiness there is. To expect thanks is really asking too much. If you get it, well, it’s like a bonus on shares on which you’ve already received a dividend; it’s grand, but you mustn’t look upon it as your due.

W. Somerset Maugham – The Back Of Beyond – Collected Short Stories – Volume 4

Happiness is when what you think, what you say, and what you do are in harmony.

Mahatma Gandhi

Words are like birds…When you publish books, you are setting caged birds free. They can go wherever they please. They can fly over the highest walls and across vast distances, settling in the mansions of the gentry, in farmsteads and labourer’s cottages alike. You never know whom those words will reach, whose hearts will succumb to their sweet songs.

More and more, he comes to realize that people fall into three camps: those who hardly, if ever, see beauty, even when it strikes them between the eyes; those who recognize it only when it is made apparent to them; and those rare souls who find beauty wherever they turn, even in the most unexpected places.

Have I told you the story of Ibrahim? I don’t think so. Well, Ibrahim was God’s beloved. That is why Nemrud hated him. He said to his henchmen: build a fire, cast Ibrahim into it…He was cruel. But it is also important to ask how everyone else behaved when calamity struck. Many just watched. Some even rushed to fetch wood, to add to the blaze. The lizard, for instance. Only a few good souls tried to save Ibrahim – like the frog. It filled its mouth with water and spat into the flames, and kept doing this, until it was exhausted. The lizard laughed and said, “You are tiny, the fire is massive, what do you think you’ll achieve with your itty-bitty water?” But the frog said “If I were to do nothing, would I be any different from you?”

Clock-time, however punctual it may purport to be, is distorted and deceptive. It runs under the illusion that everything is moving steadily forward, and the future therefore, will always be better than the past. Story-time understands the fragility of peace, the fickleness of circumstances, the dangers lurking in the night but also appreciates small acts of kindness. That is why minorities do not live in clock-time. They live in story-time.

You can be our guest for as long as you’d like. That is…very generous of you…I would not want to be a burden. Not a burden…We believe an onion shared with guests tastes better than roast lamb.

Elif Shafak – There Are Rivers in The Sky

You have to get out of your own way.

Henry Winkler – Actor, producer, director, author

“A situation in itself,” he said, “is neither happy nor unhappy. It’s only your response to it that causes your sorrow. But enough of philosophy! I’m hungry.”

Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni – The Palace of Illusions

Didn’t you tell me this past week one of the things you loved was bees and honey? Now, if that’s so, you’ll be a fine beekeeper. Actually, you can be bad at something…but if you love doing it, that will be enough

Sue Monk Kidd – The Secret Life Of Bees

Nobody made a greater mistake than he who did nothing because he could only do a little.

Edmund Burke – Philosopher

It is seldom very hard to do one’s duty when one knows what it is, but it is often exceedingly difficult to find this out.

Samuel Butler – English novelist and critic

“Man did not weave the web of life, he is merely a strand in it. Whatever he does to the web, he does to himself.”

Chief Si’ahl (Seattle) (1780-1866) – Chief of the Duwamish and Suquamish tribes

“…doing what the person paying the fees wants has come to trump personal reservations of most professionals, turning us into what philosopher Thomas Hobbes called “artificial persons, in which we set aside our own scruples to serve our clients.

This raises a question about the ethics of service. How much does our duty extend beyond meeting clients’ programs to helping them see their wishes in a larger context and their short-term requirements over the long term? Immanuel Kant’s duty ethics helps us answer such a question. He would argue that an ethical person – and I would add, an ethical professional – does what is right when viewed in the largest scale and what reason requires, regardless of the possible awkwardness of countering a client’s intentions. We should do so not because it might make us feel less artificial but because it serves clients’ real interests, whether they see it that way or not.

For clients who request things that may lead to their ruin, the professional has a duty to explain the consequence of that request, the calamity that lavish desires can cause, as Lao tzu put it. And if clients refuse to listen, we need to be ready to refuse the requests we think ill advised. That can, of course, lead to our dismissal, but this broader sense of advice also preserves what it means to be a professional: we should not do for others that which we would not do ourselves.”

Thomas Fisher – Ethics for Architects – Self Destructive Behavior

“I do not ask your absolution. I simply ask you to see that there is only one thing to do when we fall, and that is to get up, and go on with the life that is set in front of us, and try to do the good of which our hands are capable of for the people who come in our way.”

Geraldine Brooks – March

“Do you think you are doing God’s work?” (she) asks her. “Because I know that God’s work is not done through prayers and not through kissing hands. You have to get your hands dirty.”

Mohammed Hanif – Our Lady of Alice Bhatti

“Weather was often blamed for Africa’s troubles, but “what is the use of ascribing any catastrophe to nature?” Rebecca west asked herself in ‘Black Lamb and Grey Falcon’, and answered, “Nearly always man’s inherent malignity comes and uses the opportunities it offers to create a graver catastrophe.”

Paul Theroux – The Last Train to Zona Verde

“He drank an expresso macchiato and ate a croissant at a counter from where he watched the workers hurrying to and from their jobs, and he had a long overdue insight. He understood that leisure was the most expensive commodity on the planet, so rare a thing that the wealthy could not afford it. No one could, except the homeless and the deranged.”

Jeet Thayil – The Book of Chocolate Saints

“Humour can get in under the door, while seriousness is still fumbling at the handle.”

GK Chesterton

“If thou suffer injustice, console thyself: the true unhappiness is in doing it.”

Democritus

“Take care of those who work for you and you’ll float to greatness on their achievements.”

H. S. M. Burns

“He might…demonstrate in his own lifestyle, how others can live with much less and still live well. And in doing so, he would reveal the ancient maxim at the core of sustainability: that a good life for all involves freeing ourselves from insatiable desires and finding happiness in living with what we absolutely need, to ensure that those who follow us have the same opportunity”

Thomas Fisher – Ethics For Architects

“Always design a thing by considering it in its next largest context – a chair in a room, a room in a house, a house in an environment, an environment in a city plan.”

Eliel Saarinen

“We think sometimes that poverty is only being hungry, naked and homeless. The poverty of being unwanted, unloved, and uncared for is the greatest poverty.”

Mother Teresa

“People think there are answers to the world’s problems’, he said, … ‘But there aren’t any answers because the world’s fundamental problem is that most people are stupid. Never mind that they don’t buy art and don’t read books and don’t think for themselves – that’s a given…it’s another kind of stupidity – animal stupidity. Dumb instinct. People make the same fatal mistakes every generation – in war, in politics, in business. The history of the world is the history of human folly. Nothing will change.Everything gets worse.’”

Paul Theroux – The Vanishing Point – The Vanishing Point

“This is what I meant when I said the atheistic worldview requires intellectual courage. It requires moral courage, too. As an atheist, you abandon your imaginary friend, you forgo the comforting props of a celestial father figure to bail you out of trouble. You are going to die, and you’ll never see your dead loved ones again. There’s no holy book to tell you what to do, tell you what’s right or wrong. You are an intellectual adult. You must face up to life, to moral decisions. But there is dignity in that grown-up courage. You stand tall and face into keen wind of reality. You have company: warm, human arms around you, and a legacy of culture which has built up not only scientific knowledge and the material comforts that applied science brings but also art, music, the rule of law, and civilized discourse on morals. Morality and standards for life can be built up by intelligent design – design by real, intelligent humans who actually exist. Atheists have the intellectual courage to accept reality for what it is: wonderfully and shockingly explicable. As an atheist, you have the moral courage to live to the full the only life you’re ever going to get: to fully understand reality, rejoice in it, and do your best finally to leave it better than you found it.”

Richard Dawkins – The Hubris of Religion – The Four Horsemen.

“Odoric’s story bears out the idea that at the end of our exploring we arrive where we started, but we understand that starting point anew. On returning from their journey, the traveller is somehow changed, wise in new ways, having encountered radical difference and wonderful similarity, their home life and prior knowledge thrown into a new relief. Travel forces us to consider the significance of our lives, and to encounter the littleness of the human amid the planet’s variety and unknowability.

As he struggled homewards, the dying Odoric may well have felt that the earth he had traversed had itself become tiny, nothing more than a series of points on a small surface, and that the time had come to turn from earthly things to the celestial. This was not to cease roaming, but to search instead for yet other worlds. As the sun set and the blue deepened into night, Odoric received his passport into the skies, to join those released from their bodies and from earthly travels, into the brilliant circles amid the blazing stars where the soul would begin its mysterious, incorporeal journey towards the horizon of infinity.”

Anthony Bale – A Travel Guide To The Middle Ages: The World Through Medieval Eyes

“If our society were truly to appreciate the significance of children’s emotional ties throughout the first years of life, it would no longer tolerate children growing up, or parents having to struggle, in situations that cannot possibly nourish healthy growth.”

Stanley Greenspan, MD – The Growth of the Mind

“Thus, in his case, no more hoping that he would become normal again. That he would live a normal life. That what had happened would not have happened. Forget all that. Therapy taught him to give up those hopes. Hope would have to reside in something like this: hope to do some good, no matter how fucked up you are. This was worth writing down on a piece of paper, in shaky block lettering, and then pinning the paper onto the mirror in his bathroom, along with various other encouragements in the form of phrases or images, probably it looked like a madman’s mirror, but he wanted to put things up there HOPE TO DO SOME GOOD, NO MATTER HOW FUCKED UP YOU ARE.

“The whole field and discipline of economics, by which we plan and justify what we do as a society, is simply riddled with absences, contradictions, logical flaws, and most important of all, false axioms and false goals. We must fix that if we can. It would require going deep and restructuring that entire field of thought. If economics is a method for optimizing various objective functions subject to constraints, then the focus of change would need to look again at those “objective functions.” Not profit, but biosphere health, should be the function solved for; and this would change many things. It means moving the enquiry from economics to political economy, but that would be the necessary step to get the economics right. Why do we do things? What do we want? What would be fair? How can we best arrange our lives together on this planet?

Our current economics has not yet answered any of these questions. But why should it? Do you ask your calculator what to do with your life? No. You have to figure that out yourself.

Kim Stanley Robinson – The Ministry for The Future

“(She) held out her hand and he squeezed it with his left one. Then she noticed that he was missing several fingers on his right hand, but he explained that he could play the guitar anyway, because there is always a way to do what you want to do.”

“In almost every family there’s a fool or a crazy person,” (she) assured her while she concentrated on her knitting…” You can’t always see them, because they’re kept out of sight as if they were something to be ashamed of. They’re locked up in the back room so visitors won’t see them. But actually there’s nothing to be ashamed of. They’re God’s creatures too

Isabel Allende – The House of The Spirits

“The bureaucrats would bring the hammer down on the silliest, most light-hearted things. For example, they objected to a scene in which a somewhat irreverent French tourist dips his samosa in bright green coriander chutney, smiles at the other guest at the table and says, in French-accented English, ‘You know, in Eendia, every day my shit is a different colour.’”

Arundhati Roy – Mother Mary Comes To Me

“For what matters in life is not whether we receive a round of applause; what matters is whether we have the courage to venture forth despite the uncertainty of acclaim.”

Amor Towles – A Gentleman in Moscow

“The eye of the true artist doesn’t see life in the way of goods paid for. The world is ours. It is our birth-right. We take it without payment.”

Muriel Spark – The Complete Short Stories – The Fathers’ Daughters

“Our job is to give the client, on time and on cost, not what he wants, but what he never dreamed he wanted; and when he gets it, he recognizes it as something he wanted all the time.”

Denys Lasdun, architect

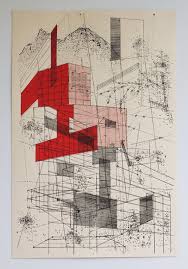

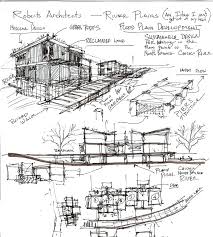

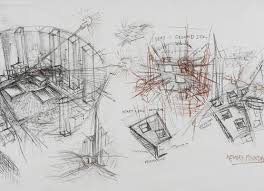

Perhaps it seems arrogant for the architect Denys Lasdun to make the above statement. But I think that we should try to see through the apparent arrogance of the statement, to the underlying truth that clients do want designers to transcend the obvious and the mundane, and to produce proposals that are exciting and stimulating as well as practical. What this means is that designing is not a search for the optimum solution to the given problem, but that it is an exploratory process. The creative designer interprets the design brief not as a specification for a solution, but as a starting point for a journey of exploration; the designer sets off to explore, to discover something new, rather than to reach somewhere already known, or to return with yet another example of the already familiar.

Important Design Factors Healthcare Facility Planning

Following are important design factors to be considered in your design approach:

- Freshness and Originality in the Design Approach – A Different Mindset – no baggage carried forward from past projects

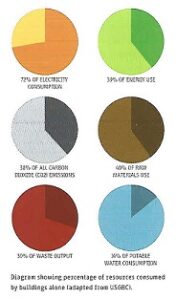

- Sustainability – Green Building Rating – Low Carbon Footprint – Hippocratic Oath: “First, Do No Harm” – focus also on IAQ (indoor air quality)-no outgassing of VOC’s (volatile organic chemicals) which can be toxic and create “sick building syndrome”.

- Flexibility of the Design to Accommodate Future Requirements – Ease of making Changes over Time – Reserved Rights of Way for Service Runs – Separation of the Structure from the Planning – Design the Basic Structure for a 100 Year Life – Primary System: RCC structure, column grid 8.4 x 8.4 M to 9.1 x 9.1 M as per current Western hospitals – built to last 100 years. Secondary system: walls and MEP – built to change after 25 years as and where necessary. Tertiary System: FF&E – furniture, fixtures and equipment – change even in the short run. Systems Separation.

- Bringing Nature into the Building – Views of Nature – Terrace Gardens – proven fact that it enhances patient recovery

- Natural Light and Ventilation as a Design Factor – light wells, courtyards, alphabet architecture?

- Energy Efficient Design – MEP design, passive solar

- Climate Change and Extreme Weather Events Resilient Design – eliminate expensive equipment in basements? Overdesign HVAC cooling systems by 20% to cope with heat waves and future increased AC load?

- Ease of Wayfinding by Design for Patients Under Stressful Mindsets – colour coding floors, supergraphics, views to the outside to help orientation within the building

- Use of Colour and Artwork in Interior Spaces – see above. Artworks as events marking where you are, help in orientation

- Patient Centric Design – A Hospital beyond “A Doctor’s Workshop” – keep the well-being of the patient and visitor uppermost

- Therapeutic Rooftop Garden – museum of medicinal plants

- Water Conservation – Efficient Fixtures – rainwater harvesting

- Optimised HVAC Design – overdesign to take care of future unanticipated AC load during heat waves?

- Passive Solar Features – Sun Shading Devices – Corbusier’s brise soliel

- Evidence Based Design – Using Environment Behaviour Studies – a scientific basis for taking design decisions

- “At the Beginning of a Project the Big Decisions Get Made” – The Importance of Strong Conceptual Design

- Use of Design Charrettes to Determine Real Needs – Participation of Staff/Doctors in Conceptual Design – get staff/doctors buy-in into the design by hearing them out and responding to their comments

Specialized Hospitals: Design and Planning

Edited by Rebel RobertsThe Healing Wheel of the Environment

By Tom Danielsen

“The effect in sickness of beautiful objects, of variety of objects and especially of brilliancy of colours is hardly at all appreciated. People say the effect is only on the mind. It is no such thing. The effect is on the body too. Little as we know about the way in which we are affected by form, by colour and light, we do know this, that they have an actual physical effect. Variety of form and brilliancy of colour in the objects presented to patients is an actual means of recovery.” Florence Nightingale, 1885.

Evidence-Based Design

Internationally, there is an increasing focus on Healing Architecture and Evidence-Based Design (EBD). EBD is seen as a parallel to evidence-based medicine, and is defined as “the deliberate attempt to base design decisions on the best available research evidence…Evidence-based healthcare designs are used to create environments that are therapeutic, supportive of family involvement, efficient for staff performance, and restorative for workers under stress. An evidence-based designer, together with an informed client, makes decisions based on the best information available from research and project evaluations.” Hamilton DK (2003) The Four Levels of Evidence -Based Practice. Healthcare Design, November 2003.

Evidence-Based Design and the Healing Wheel of the Environment

On the basis of EBD, the DNU consultant group has developed “The Healing Wheel of the Environment”, which forms the planning foundation for the entire project. As EBD is a relatively new discipline, and limited in many respects in its scientific foundation, the logical consequence is that only “evident” areas are included in the wheel, which can be extended at any time. The twelve components of the Healing Wheel of the Environment are:

- Empowerment and ergonomics

- Daylight

- Single-bed rooms

- Acoustics

- Artificial light

- Access to the landscape

- Communication and logistics

- Textures

- Indoor climate

- Art

- IT

- Design and décor

Empowerment and Ergonomics

The patient must as far as possible be able to regulate the light, heating and music in the patient room. Via bedside PCs, patients will have access to their own journals and will be able to see the times of planned examinations, test results, etc. Improved ergonomic design will help to ensure less fatigue and stress.

Daylight

Daylight is not just important for our sense of well-being, but also for our health. Daylight helps to ensure that our circadian rhythms are correctly adjusted; it also lifts the general atmosphere, and has an anti-depressant effect. Patients in rooms will windows, particularly windows with green landscapes outside, have shorter periods of convalescence and fewer complications, and require less pain-relieving medicine. Careful and early planning of natural light can reinforce the positive effect of day light and help to prevent the problems that natural light can also cause, such as over-heating and dazzling. Besides improving personal comfort, the conscious use of daylight thus has both an environmental and an economic dimension.

Single-Bed Rooms

Research shows that single-bed rooms confer a number of benefits, including fewer hospital-acquired infections, fewer medication errors and a lower noise level. Single-bed rooms also mobilise the patients when they get up to eat, or meet other patients. They also provide privacy for conversations with hospital staff, and thereby a basis for better treatment. The arguments in favour of multiple bed rooms are usually that they are less expensive (to build and operate), but in fact the shorter periods of admission to hospital indicate that single-bed rooms are more economic from the point of view of society.

Acoustics

A room’s acoustic properties determine how sounds are disseminated there. The noise level of hospitals is notoriously high, with many simultaneous and different noise sources, such as people walking, talking or working, beep-sounds from equipment, and transportation noises – all in spaces with hard surfaces, due to cleaning requirements. A lower noise level can reduce stress for both patients and staff and help to give patients the peace and quiet they need. Good acoustic qualities contribute significantly towards a good indoor climate, and are best secured by selecting the right construction principles, an appropriate internal organisation and good surface materials.

Artificial Light

Artificial light must fulfil both functional and aesthetic needs. It must be flexible and variable and provide a sense of well-being, but must also be capable of being switched to diagnostic lighting, for example to examine changes in skin colouration. The choice of fittings and light sources must comply with both functional and atmospheric needs. Artificial light will be used in combination with daylight, and will take over the illumination function when daylight alone is insufficient.

Access to the Landscape

Patients must have access to gardens and landscaped areas. Nature has a positive effect on stress and fatigue, and its promotion of health and healing is well documented. Randomised studies have shown that a view of and access to natural surroundings can have a pain-relieving effect in itself. Gardens also cause patients to move around more, which has a positive effect on their healing, e.g. by encouraging the release of endorphins through exercise. They also provide suitable places to meet and talk with people.

Communication and Logistics

The New University Hospital in Aarhus is in dialogue with its surroundings: the existing hospital, the future new buildings and the landscaped environment. The hospital’s flow is clear, comprehensible and physically convenient for all user groups and staff. The hospital is built up around the large landscape garden, the Park, which is its most important physical landmark. The squares and arcades of the various blocks each have their own individual form and décor, and thereby their own identity. The building information will be supported by “speaking signs” – hand-held receivers which can read out signs and information boards in Danish, English, German or Spanish.

Textures/Surfaces

Surfaces influence and involve all of the senses. If we are to realise the vision of a clean, sensually rich, aesthetic, healthy and comfortable workplace, all of us – both the hospital, the occupational health services, organisations, researchers, advisers and public authorities – must work to promote a healthy working environment. All kinds of environmental factors should be given consideration in the project, and products with a positive effect on the indoor climate, including natural materials, should have preference. Efforts must be made to ensure that a large amount of the materials used can be recycled, and that the building materials are themselves based as far as far as possible on recycled materials. Partial or complete wood cladding should be used in some of the public areas, such as the Forum, arcades and squares.

Indoor Climate

The indoor climate of a building can influence a person’s health, well-being, quality of life and productivity. In a hospital building the patients are in a vulnerable health condition, and high productivity is expected of the staff. Accordingly, the indoor climate is of considerable importance to all who spend time there. The basic principle behind the maintenance of an optimum indoor climate is that the building and its physical qualities should enhance the indoor climate as far as possible. This is primarily done the use of heavy, well-insulated constructions and a combination of appropriate window areas, glass quality and sun screening to guard against over-heating or insufficient cooling. The building is then supplemented with technical installations such as heating and air conditioning equipment, which support the building’s physical qualities. This minimises dependence on the technical installations, which, besides conferring benefits in terms of energy use, ensures an optimum indoor thermal climate. In atmospheric terms, the ideal indoor climate is achieved by utilising materials which release no gases, or only release gases in tiny quantities, and via the use of filtered and conditioned air from outside.

Art

The other components in the Wheel are “rational and evident”. The rational and the irrational are inseparable; they define each other and are thereby interwoven. To meet art is to encounter something else. The appropriate relationship between the visual arts and architecture, and their modes of integration, is a perennial question. Art in the public arena offers free and enriching experiences. The construction of the New University Hospital Aarhus presents an exceptional opportunity to create original works in special places. By integrating art at as early a stage is possible, the patients, staff and visitors can be presented with larger and more complex works.

IT

The hospital of the future is a digital hospital. Wireless IT infrastructure is the natural starting point to enable both staff and patients to easily send and receive information in digital form. Pervasive computing can make health care independent of time and place, and can improve communication and coordination between the various levels of the health sector.

Design/Décor

In this context, design should primarily be understood as a combination of the traditional view of design and the modern perspective on design as a rational process of problem solving. At the New University Hospital design must contribute to improved solutions for staff, patients and relatives. The conscious use of well-designed, well-functioning products, furniture or fixtures brings benefits which extend beyond the immediate target group. Equipment design which combines advanced technology and attractive appearance with user-friendliness and good ergonomics will contribute to an improved working environment for the staff, with a reduced risk of operational errors and work-related injuries. A beautiful and friendly design without an overly mechanical appearance will also help to instil confidence and reassure nervous patients. In the same way, a well-designed patient room with a good décor and choice of materials will satisfy both the staff’s need for an efficient environment and the patient’s need for a friendly and confidence-inspiring space, in which elements from the domestic sphere help to call forth desirable associations and atmospheres, and in the final analysis contribute to more rapid healing and a shorter stay in hospital. The interior project, which encompasses both furniture and fixtures, must support and complement the overall vision of a modern, IT based and efficient hospital which focuses on the individual.

Wear The Old Coat, Buy The New Book

- It’s called reading, it’s how people install new hardware in their brains

- He said, “me or books?” I sometimes remember him when I buy new books

- In my dreams books are free and reading makes you thin

- Abibliophobia: Uh-bib-li-uh-fo-bee-uh Fear of running out of reading material

- The great thing about books is that there are no commercials

- I disappear into books. What’s your superpower?

- Booktrovert: A person who prefers the company of fictional characters to real people

- Books are a uniquely portable magic

- I am not addicted to reading. I can finish as soon as I finish the next chapter

- Anyone who has time to clean is not reading nearly enough

- Too many books? I think what you mean is not enough bookshelves

- That major sleep disorder you have is called reading

- Books are the very best defence against unwanted conversation

- My workout is reading in bed until my arms hurt

- A book commits suicide every time you watch a reality show

- Books are just TV for smart people

THE CHALLENGE OF PREDESIGN PLANNING

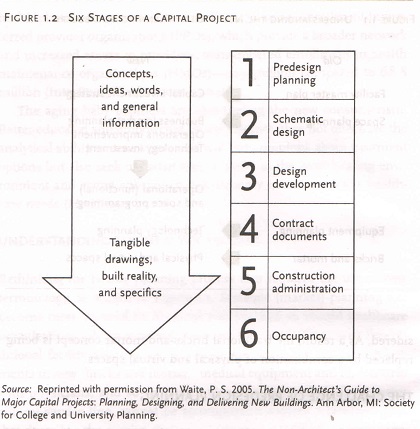

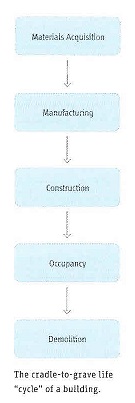

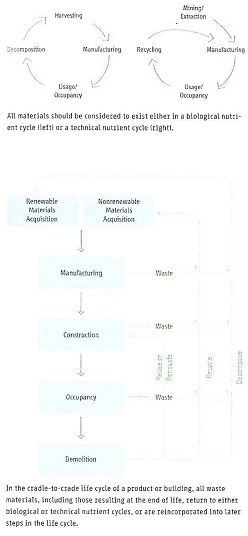

The planning and delivery of a major capital project can be divided into six stages, as shown in the figure below:

The first stage of predesign planning – the focus of this note – includes general concepts and ideas in the form of words, numbers and conceptual diagrams. Preliminary space estimates are used to develop a facility master plan and to generate project cost estimates early .Once specific projects are identified and approved, the detailed operational and space programming begins; when this is completed, the design architect can start the schematic design stage. Each subsequent phase brings more knowledge and detail about the project and has its own cast of players. Nearing the final phases, the concepts and ideas are translated into tangible architectural floor plans, drawings of construction details and the eventual reality of the three-dimensional building.

Predesign planning can be defined as the process of determining the following:

• Right services consistent with the organizations strategic initiatives, market dynamics, and business plan, at the

• Right size based on projected demand, staffing, equipment, technology, and desired amenities, in the

• Right location based on access, operational efficiency, and building suitability, with the

• Right financial structure – for example, owning leasing or partnering.

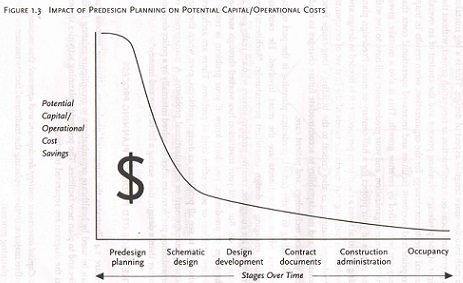

Predesign planning is the stage where the healthcare executive has the most influence on the potential success of the final project. His or her opportunity for input decreases as each subsequent stage passes. The opportunity to reduce both the initial capital cost and the ongoing operational costs is also greatest during the predesign planning stage, as shown in the figure below:

With the prospect of a new building project, healthcare executives tend to short-circuit or bypass the predesign stage to rush into the more tangible aspect of design. This is a big mistake. A premature focus on a construction or renovation project, without the rigor of a predesign planning process and the context of an overall capital investment strategy for the organization, often results in in inappropriate and overbuilt facilities and increased operational costs that may not be justified by revenue growth. This is also a mistake, given that you, your organization and your predecessors will have to live with the results of your project for half-century or more. Predesign planning is critical from a short term-term perspective: it is needed to design and construct a building that meets the needs of the first set of occupants. Predesign planning is also critical to the building’s long-range functional life and it’s adaptability to accommodate future changes in medical practice, technology, and patient care.

Predesign planning is the part of the process where non-architects are the most involved. There should be caution against engaging a design consultant prematurely. Architects and engineers are energetic, creative problem solvers who are really good at what they do. But until your institution has worked through some of the steps of predesign, you don’t know if your problem is really a design problem or some other kind of problem. There are architects who tend to see all problems as design problems, even when they’re actually management or organizational problems. A management or organizational problem can often be solved internally by a policy decision thus saving a lot of time and money.

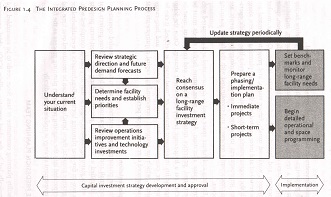

THE INTEGRATED PREDESIGN PLANNING PROCESS

The figure below illustrates the integrated planning process that can be used by healthcare organizations to reconfigure existing facilities and to plan new facilities. The predesign planning activities shown in the diagram are separated into two:

1. Capital investment strategy development and approval: this includes five major activities (replacing the traditional facility master planning process).

2. Implementation: this includes the detailed operational and space programming for designated projects and the establishment of benchmarks to monitor long-range facility needs as the strategy is periodically updated.

Capital Investment Strategy Development and Approval

The predesign process begins with the collection of baseline data and a review of the organizations current situation, including campus access and circulation, bed utilization and configuration, space allocation and layout, and infrastructure issues. Current market dynamics, workload trends, future vision and projected demand are also reviewed and incorporated into the facility planning process, along with the organizations institution-wide and service-line specific operations improvements initiatives. Planned technology investments are currently reviewed and coordinated with the facility planning process.

Existing and future space need is documented and compared with current space allocation. At this point, future facility needs must be determined, priorities must be established, and consensus must be reached on a long-range facility investment strategy. Once the long-range facility investment, or “road map”, is defined, it can be divided or categorized into immediate, short-term and long-range projects, which are assigned corresponding capital requirements that are sequenced over a multi-year period.

Implementation

With the phasing/implementation plan in hand, detailed operational (functional) and space programming can begin for those projects that are identified as immediate priorities, along with short-term projects for which planning needs to begin so that they can be completed in a two-to-five year planning horizon. Benchmarks are established for long-range projects; these benchmarks can be monitored over time and incorporated into the ongoing predesign planning process as the facility investment strategy is updated periodically.

This note on “Predesign Planning” has been adapted from the book “Healthcare Facility Planning: Thinking Strategically” by Cynthia Hayward, and is fully endorsed by me as relevant and necessary.

I encourage you to read this very good book; it is available on Amazon.in.

The Project Launch Phase

The following are key points to remember about the project launch phase:

• Spend sufficient time defining the scope, cost, and the schedule of the project.

• Develop a budget and schedule early.

• Complete the master facility plan and operational and space programming processes before entering the design phase.

• Make smart land-acquisition decisions. Acquire sufficient land to prevent the land from driving the design, to allow for future expansion, and to accommodate future changes in healthcare delivery and technology.

• Evaluate potential joint-venture opportunities and their impact on capital and operating cost.

• Assemble the key members of the project delivery team.

The Project Delivery Team

The following are key points to remember about the selection and organization of the project delivery team.

• Select external team members – project manager, lead architect, specialty consultants, and construction manager – during the launch phase.

• Organize the Facility planning Committee first. This committee should include representatives from the board and medical staff building committees.

• Identify people from the board, from medical staff, and from the community as “project champions” and involve them in the process.

• Select members for the departmental task forces, and then involve them in the development of the master facility plan, the Operational and Space Planning (O & SP) process, and the design phase. These forces should include physicians, staff, and volunteers from various departments.

• Base selection of key external staff members on qualifications, experience with similar projects, and chemistry with internal team members.

This note on “The Project Launch Phase” and “The Project Delivery Team” has been adapted from the book “Launching a Healthcare Capital Project” by John E. Kemper, and is fully endorsed by me as relevant and necessary.

I encourage you to read this very good book; it is available on Amazon.in.

Proposed 250-375 Beds Model Hospital

The Ability to Accommodate Change

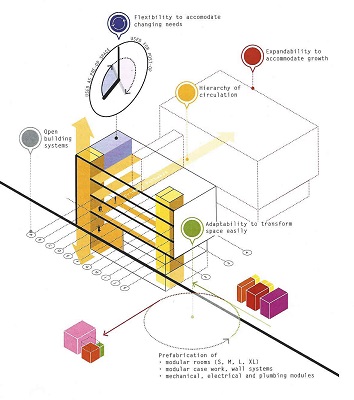

Hospitals and large healthcare campuses need to be able to accommodate change. Buildings that cannot change, and especially healthcare buildings, which often remain in operation for 50-100 years or longer, are at risk of premature obsolescence. There are three ways in which buildings and building complexes can transform and accommodate changing needs: through flexibility, adaptability and expandability. Flexibility involves the ability of a given space, department, building or campus to accommodate changing needs with little or no physical reconfiguration. Adaptability involves planning and constructing buildings or building elements with the capability to transform space easily with the least amount of physical, material and economic impact. Expandability involves planning to accommodate growth and change in a coherent and logical way. It requires planning infrastructure and circulation in a way that anticipates future growth.

A change-ready hospital. Source: Heinle, Wischer and Partner

Primary Drivers

The healthcare context is incredibly dynamic and influenced by constant changes in medical science and technology, healthcare policy and regulations, demographic transformations in both populations served and caregivers, and evolving clinical practices and approaches. Collectively not only are these forces increasing in their impact but also the arte and pace of change are accelerating. Healthcare as delivered 50 years was fundamentally different than today. Facilities that were designed and built then and are still in use were not conceived to easily accommodate changing healthcare needs, practices, and technologies. It was simply impossible then to imagine the scope of changes that have occurred over the life of these facilities, and it will be increasingly impossible to imagine healthcare needs over the next 50 years or how healthcare will be delivered. Therefore, healthcare facilities must be able to accommodate not only changes we can anticipate but also changes we cannot even imagine.

Design Considerations

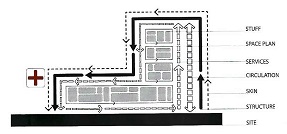

The first principle of accommodating change is to design the overall building for layers of change, as out lined by Stewart Brand (1995) in How Buildings Learn: What Happens After They’re Built. The fundamental principle is that buildings designed to accommodate layers of change have long lives. These layers consist of site, structure, skin, circulation, services, space plan and stuff. The key is to design buildings so that more stable elements (“hard spaces”), such as structure and core infrastructure, support frequent changes to the more flexible elements (“soft spaces”) around them.

Layers of change. Source: Clemson University Architecture + Health Program

A truly open building system is also designed with a clear hierarchy of circulation where the primary pathways are stable even in the event of changing programmatic use. In cities, we rarely change the location of streets to accommodate the needs of individual development. The most stable elements of the city are its streets and movement systems. Healthcare planners and designers need to employ urban design principles when designing large healthcare facilities and campuses, where movement systems and infrastructure are aligned and stable. Medical planning of a campus, the equivalent of a city block, can then constantly change and transform. Within an open building framework designed for layers of change, modularity can be employed to accommodate flexibility, adaptability, and expandability. Modularity can occur at multiple scales, from building components and individual rooms to planning strategies that allow departments and larger areas to transform. A key aspect of modularity is that it allows for prefabrication. Standardized and prefabricated modules can also lead to improved construction quality in controlling manufacturing conditions, lower waste, and improve the speed of construction. Finally, modularity enables the delivery of high-quality healthcare settings when and where it may be difficult if not impossible to build on-site with locally available materials, expertise and labour. Prefabricated modules are becoming commonly produced at multiple scales:

- Prefabricated and modular casework, headwalls and wall systems

- Prefabricated mechanical, electrical, and plumbing modules

- Prefabricated and modular rooms (toilets, patient rooms, and other spaces that are repeated multiple times in the design and construction of healthcare facilities)

Finally, modularity should be considered in the overall planning of departments and functional areas within them. Standardized clinical modules not only support the implementation of prefabricated building elements but can also help standardize care practices with replicated and pretested design elements.

This note on “The Ability to Accommodate Change” has been adapted from “Chapter 22 – Epilogue: The Future of an Architecture for Health by David Allison, Eva Henrich, and Edzard Schultz” in the book “Architecture and Health: Guiding Principles for Practice Edited by Dina Battisto and Jacob J. Wilhelm” and is fully endorsed by me as relevant and necessary.

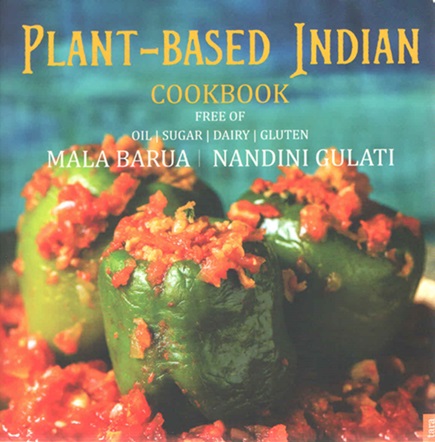

Plant-Based Indian Cookbook: Oil, Sugar, Gluten and Dairy Free Vegetarian Recipes

Nandini Gulati and Mala Barua Foreword: Maneka Sanjay Gandhi

Foreword: Maneka Sanjay GandhiFormer Minister, Ministry of Women and Child Development

One of our 33,000 divinities in India is Shakambari, Goddess of Hampi, Karnataka. Every year, on her festival day, she is offered 63 vegetables. They probably have a checklist coming down the centuries because I have yet to find someone who can name that many vegetables offhand. Sadly, we have stopped paying attention to our vegetables and old varieties of grains and seeds. We had over 90,000 varieties of rice in 1960. We now have only 23,000 varieties. Once we had had long red bhindi (okra). No one has seen it for the last 50 years.

I would like to think that India is still largely vegetarian. But the problem is that people mistake drinking milk to be vegetarianism. If the meat of the cow is non-vegetarian, how can the milk from the same animal body be vegetarian? It is for this reason that milk drinkers get the same diseases as meat-eaters – gout, heart disease, cancer, obesity, kidney failure, diabetes…to name a few!

Cows and buffaloes in India, as in most of the world, are riddled with disease. They have been mutated into milk machines and most of them suffer from cancers, leukaemia (Bovine Leukosis Virus or BLV), mastitis, foot and mouth disease, pneumonia, ketosis, brucellosis etc. And are kept alive on antibiotics. I use the word ‘most’ because it is true in over 70-80% cases. All these diseases are zoonotic – which means drinking their milk could make you vulnerable. In fact, scientific studies have repeatedly shown the presence of BLV cells in women’s breast cancer, for instance.

All these animals are given a daily injection of oxytocin, which is a hormone not only to extract the milk faster but which enters the blood and milk stream of the animal. This can cause in humans, everything from early puberty to breast, uterine and prostate cancers, bad eyesight, an imbalance in hair production and more. Milk has been directly related to cancers and diabetes.

The human body is simply not designed to absorb meat or milk. Unlike carnivores, we don’t have canines, claws or slit-eyes with wider vision. Our intestines are too long to eliminate meat easily and our saliva is not acidic. All babies cry when introduced to non-mother’s milk and their burps become smelly. Every child has to be threatened into drinking milk – because the body rejects the idea and it knows best.

Most of these ailments can be reversed through a healthy vegan diet. Doctors in the West have already started a movement in reversing lifestyle diseases through a ‘whole food plant-based’ diet. Ayurveda is a fully researched branch of science that does the same.

Unfortunately, in India people tend to believe allopathic doctors who know very little about diet since the essential science of food and its impact on the human body is not included in the curriculum of medical schools. When a doctor or even a dietician, orders than an ulcer patient should have a glass of cold milk, he will do so not knowing that milk turns to acid in the stomach and will eventually enlarge the ulcer.

Meat eating has become aspirational – just as smoking and drinking beer was in the 1950s. Cooking shows on TV glorify meat and fish dishes. International chefs often scoff at vegetarian food (except if there is cheese or paneer in it) as being boring. However, if you would take a survey of their health issues, most of them will have high blood pressure, high cholesterol, a narrowing of the arteries and almost all of them are overweight.

You don’t have to be vegan to be kind to animals, though taking a moral stand of not causing suffering is extremely laudable. You don’t have to be concerned about the world and its survival even though the methane emitted by animals grown for meat is causing the world to become warmer and the water to dry up. But you have to be kind to yourself. Just as you would not run your stove on petrol, don’t put inappropriate food into your body.

Veganism is not that easy to incorporate into your life. Meat is a drug and once addicted to it, it takes a while to give it up. I would advise that when you are on the road to veganism, stay away from meat-eating environments and people for a while as the smell of cooked meat can bring craving. There will be a few slips along the way but once your body sheds its addiction and goes forward to good health, there is no turning back.

India is a very exciting place to be vegan. There are so many nutritious but forgotten vegetables and grains in India that need to be reintroduced into our daily diet. Black rice from Meghalaya, pineapples from Manipur, 200 varieties of rajma ranging from white to purple, summer and winter millets, thousands of varieties of leaves, berries and fruits that even I need to learn about…

I am as fierce about the organic food movement as I am about animals and nature. I held the first organic festival in India more than 20 years ago. When I became a minister again, I started an annual organic festival in Delhi. Hundreds of women brought produce from all over India. Now these festivals have spread from Delhi to Ahmedabad, Mumbai and Chennai. Customers for organic food have increased every year. I look for women who have regenerated old seeds and old ways of cooking and give them national awards.

I congratulate Maya and Nandini for creating recipes in this book that are easy to cook and are for everyday meals. Vegan and wholesome does not mean exotic or pretentious. It is simply good food with all the bad things kept out – refined and processed ingredients, sugar, oil etc. They have even accommodated the new trend of gluten-free food.

Good food deserves celebration. Good food changes relationships and moods. Good health changes your life and you will never know what it is till you achieve it. This book is a guide. Use it to touch the sky.

From The Authors

Climate Change and Food Choices

Our food has a huge impact on greenhouse gas emissions. Some estimates put it at high as 51% of total emissions. Clearing land for livestock used for meat and dairy is the leading cause of forest degradation. Using pesticides and artificial fertilizers is one of the leading causes of water contamination, degradation of soil quality and loss of bees and insects that are so critical for biodiversity.

Eating seasonal and local food is encouraged as imported food contributes to ‘food miles’ or emissions linked to the distance the food has to travel to get to you.

It is no coincidence that the food that is best for the planet is also best for our health. Locally grown, seasonal, organic and plant-based food has the lowest emissions. Broadly speaking, fruit from native trees requires the lowest input and resources, be it land, water or fertilizers. Fresh seasonal fruit is also easily digestible and bursting with nutrients. Locally grown millets are less resource intensive than the popular rice and wheat varieties. Most local millets require no irrigation and are naturally resistant to pests and insects.

As a thumb rule, if you wish to lower your personal carbon emissions, every meal presents an opportunity to do so. Eat more organic, seasonal, local and fresh plant-based food and you will be cutting out nearly 95% of your food emissions.

Whole Food Plant-Based (WFPB) for Health

Whole food plant-based is more than a ‘diet’ – it is a lifestyle of wholesome eating which shuns all animal-based foods like meat, eggs, dairy, honey and all refined food like oil, sugar, refined white rice and flour etc. It focuses instead on fresh fruits, vegetables, beans, legumes, tubers, seeds, nuts and whole grains.

Additionally, we have gone a step further to curate recipes without wheat to help people looking for gluten-free options. Due to the over-commercialization of wheat, the grains available nowadays are hybrid versions with a high percentage of gluten. Many people are reacting to this high level of gluten showing symptoms of bloating, weight gain, digestive issues and allergies. There are many medical doctors, nutritionists, health coaches and dieticians who recommend this way of eating to prevent and even reverse common lifestyle diseases like diabetes, heart disease, cancer, hormonal issues and auto-immune conditions, among others. To learn more scientific information about this lifestyle, you can see our recommended list of films and books at the end of this note.

How to Make the Change

Switching to a whole food plant-based diet overnight can be a daunting proposition for many, so we recommend a slow and steady approach. Don’t worry if you can’t do everything at once. It’s a skill to be learnt.

We recommend you add a big and juicy salad before every meal. The secret to eating healthy is to eat plenty of fruits and vegetables and as much raw or ‘sun-cooked’ food as possible. In India, we do not give much thought to our salads, lackadaisically cutting up half a cucumber, tomato and some onions as an afterthought to a meal.

The Time Is Now

They say the best time to go for a healthy diet and lifestyle was yesterday and the second-best time is right now!

Today, the same can be said for the health of the planet at large too. Plant-based is the future of food. Thousands across the world are switching their war of eating to more and more plant-based and wholesome food for better health, climate change considerations and most importantly compassion towards animals.

Begin today!

Five Contemplations by Thich Nhat Hanh

This food is the gift of the whole universe: the earth, the sky, numerous living beings and much hard, loving work.

May we eat with mindfulness and gratitude so as to be worthy to receive it.

May we recognize and transform our unwholesome mental formations, especially our greed, and learn to eat with moderation.

May we keep our compassion alive by eating in such a way that we reduce the suffering of living beings, preserve the planet, and be aware of the consequences to our environment.

We accept this food so we may nurture our loved ones, strengthen our community, and nourish ur ideal of serving all living beings.

Resources

In your quest to know more about the vegan and whole food lifestyle, we recommend that you explore the following books, videos and films. They provide the scientific proof and case study evidence of the health, environmental and spiritual benefits of a plant based diet.

Books:

World Peace Diet by Will Tuttle

Eat to Live by Dr Joel Fuhrman, M.D.

How Not to Die by Dr Michael Greger, M.D.

The China Study by T. colin Campbell

WHOLE by T. colin Campbell

Reversing Diabetes by Dr Neal Barnard, M.D.

There is a cure for diabetes by Dr Gabriel Cousens, M.D.

Prevent and Reverse Heart Disease by Dr Caldwell Esselstyn, M.D.

The Starch Solution by Dr John McDougall, M.D.

Milk: A Silent Killer by Dr NK Sharma

Healthy at 100 by John Robbins

Undo it by Dr Dean Ornish M.D. and Anne Ornish

Eat to Live by Dr Joel Fuhrman, M.D.

Disease proof Your Child by Dr John McDougall, M.D.

You can also search for the video lectures by these authors on You Tube

You Tube Videos:

Vegan Video Life Connected

PETA Glass Walls

The Last Heart Attack by CNN’s Dr Sanjay Gupta

Horrors in the Indian Dairy Industry

Films and Documentaries:

Earthlings (www.earthlings.com)

Forks over Knives(www.forksoverknives.com)

Cowspiracy-The Sustainability Secret www.cowspiracy.com

May I Be Frank? www.mayibefrank.com

Eating www.eatingthemovie.com

Vegucated www.getvegucated.com

What the Health (Health)

The Game Changers (Sports and Fitness)

Dominion (Animals)

A Prayer for Compassion (Spirituality)

Most of these films are available on Netflix or YouTube

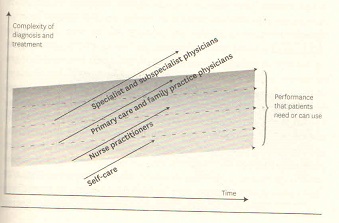

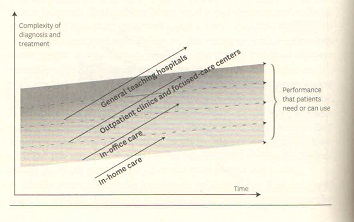

Levels of Care: Primary, Secondary, Tertiary

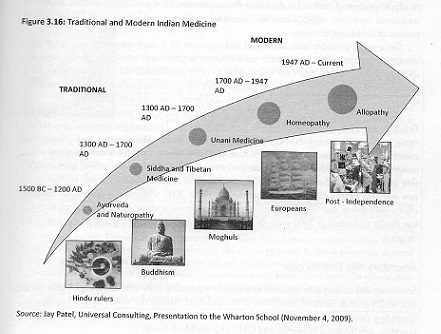

There are three classes of primary care practitioners, distinguished by increased sophistication in their level and type of training, as well as by their historical emergence (see figure 3.16) at the lowest level there is a staggering number (roughly 1.1 million) of individual practitioners without any staff (and probably without any qualifications) who are owner-operator of their own clinics; such practitioners are labelled “quacks”. Roughly 80 percent of these are rural establishments located in villages.

One of the reasons healthcare in the USA is so expensive is that doctors have to pay high premiums for malpractice insurance, and this cost gets passed on to the patient. Also, unlike India, there are no “quacks”.

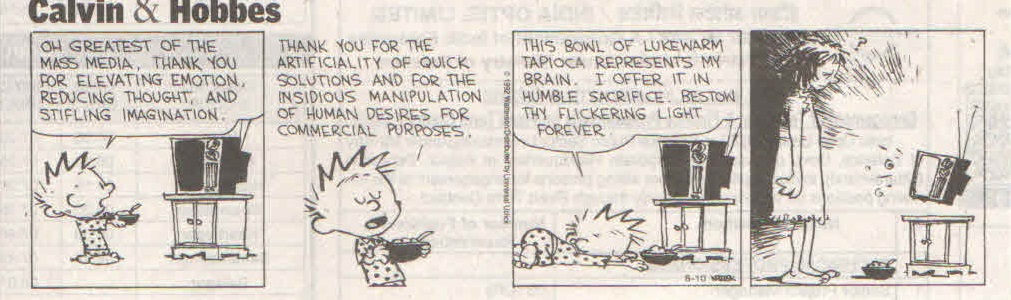

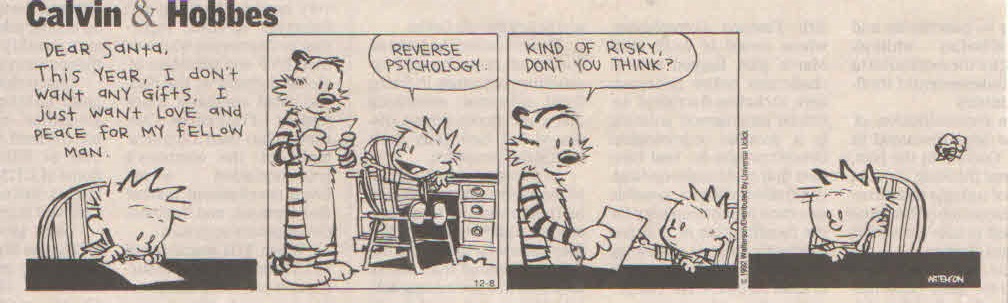

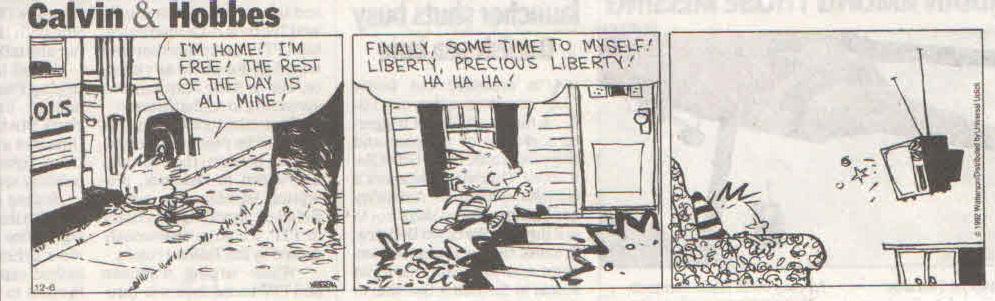

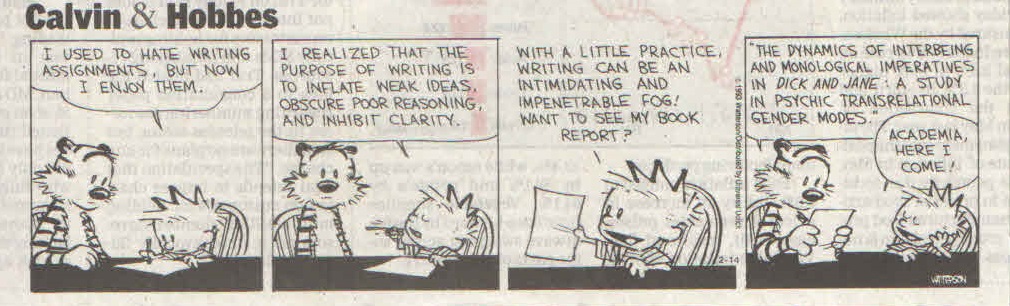

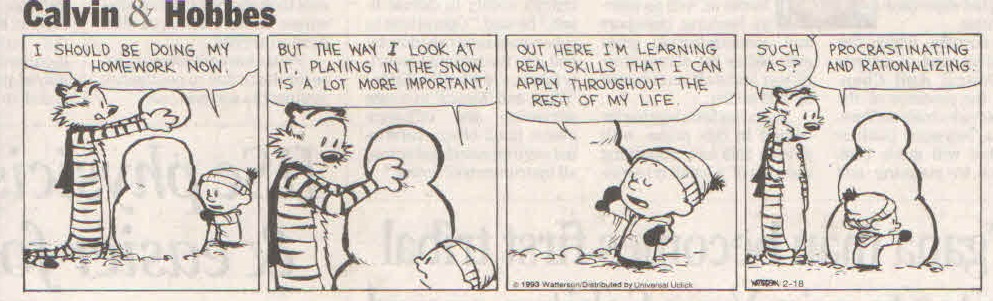

Calvin and Hobbes is my favourite comic strip.

This illustration from Boccaccio’s Decameron shows the Roman emperor Galerius being bled by leeches. According to the text, his symptoms included putrefaction and abominable stench.

A handy medical reference text for physicians was the “leechbook”, perhaps so-called because physicians ere nicknamed “leeches”, from the habit of using these worm-like creatures to drain blood for almost any ailment. Most leechbooks contained remedies of the time gathered indiscriminately from a vast array of sources.

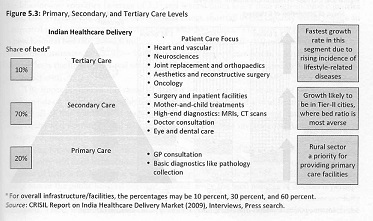

A traditional means to segment delivery across countries is primary, secondary, and tertiary care. These levels have been defined in a variety of ways by a variety of organizations:

Primary care is medical care provided by the clinician of first contact for the patient. Typically, the primary care physician is a general practitioner, family practitioner, primary care internist, or primary care paediatrician. Primary care may also be administered by health professionals other than physicians, notably, specially trained nurses (nurse practitioners) and physicians assistants. Thus, it is the nature of the contact (first compared with referred) that determines the care designation rather than the qualifications of the practitioner.

Secondary care is medical care provided to a patient when referred by one health professional to another with more specialized qualifications or interests. Secondary care is usually provided by a broadly skilled specialist such as a general surgeon, general internist or obstetrician.

Tertiary care is provided on referral of a patient to a subspecialist, such as an orthopaedic surgeon, neurologist, or neonatologist. A tertiary care centre is a medical facility that receives referrals from both primary and secondary care levels and usually offers tests, treatment, and procedures that are not available elsewhere. Most tertiary care centres offer a mixture of primary, secondary, and tertiary care services so that it is the specific level of service rendered rather than the facility that determines the designation of care in a given study.

Primary Care

In terms of overall infrastructure capacity, organized primary care sites comprise an estimated 95 percent or more of India’s delivery capacity, with secondary and tertiary care accounting for 3 and 2 percent, respectively.

There are three classes of primary care practitioners, distinguished by increased sophistication in their level and type of training, as well as by their historical emergence (see figure 3.16) at the lowest level there is a staggering number (roughly 1.1 million) of individual practitioners without any staff (and probably without any qualifications) who are owner-operator of their own clinics; such practitioners are labelled “quacks”. Roughly 80 percent of these are rural establishments located in villages.

At an intermediate level are practitioners of the Indian systems of medicine (ISM): ayurveda, unani, siddha, naturopathy and yoga. For centuries, they were the traditional suppliers of primary care. During the nineteenth century, these groups were supplemented by practitioners of homeopathy. Collectively they have been referred to as ISM&H, or the more convenient label AYUSH practitioners. These practitioners are typically concentrated in small towns and rural areas. Roughly 75 percent of the populace utilize their services, given their low cost and accessibility. This traditional form of medicine is very popular because the providers consider personal, social, and cultural dimensions of illness and care.

At the highest level are providers of allopathic medicine, which the Indian government began to favour post-independence. The dividing line between AYUSH and allopathic is codified in law and institutionalized in different medical colleges for both. In practice, things are less clear cut, as some practitioners may practice across these boundaries .Neither allopathic medicine nor AYUSH is closely regulated internally or externally, and neither is standardized in terms of qualifications.

Most allopathic physicians are primary care practitioners in solo practice or in small group practices (called “polyclinics”). Three-quarters of them are located in urban areas, providing perhaps a broader range of services than the preceding practitioners, staffed with employed personnel and one or more trained physicians. Roughly one-quarter of the Indian population uses the modern allopathic medicine practitioners who are located primarily in urban areas and who generate nearly 90 percent of healthcare revenues; three-quarters of the population avail themselves of traditional medicine, which is heavily located in rural areas and which accounts for only 10 percent of healthcare revenues.

Secondary and Tertiary Care

Secondary and tertiary care rendered in hospitals was traditionally offered through public facilities which provide services free of cosy or at subsidized rates to the lower-income populations. Secondary facilities are found at different administrative levels in each state, including district hospitals, sub-divisional hospitals, and CHCs (at the block level).

Since the mid-1070s (and especially after the 1991 market liberalization), the Indian government has provided a host of incentives to expand facilities in the private sector, including land concessions, tax breaks, low-income loans from public banks, transfer of public hospitals to private firms, duty exemptions for imports of medical equipment, rebates in customs tariffs, reimbursement for government employees, and allowances for hospitals to be run as tax-exempt “trusts.”

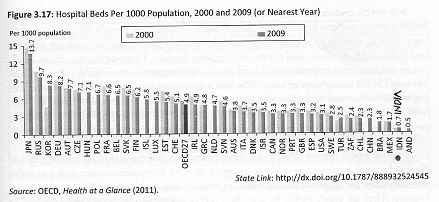

Not surprisingly, statistics on India’s bed capacity also vary widely. The count seems to depend on whether or not nursing homes are included. Across all facilities, there are 1.2 million to 1.7million beds, if one considers only hospitals with 30 or more beds, the count is 680,000 private hospital beds. Despite the large number of hospitals and beds, world benchmarks suggest that India suffers from a lack of capacity (see Figure 3.17). Compared to OECD and select other nations, India ranks second to last with 0.7 beds per 1000 population (versus the OECD average of 4.9). India ranks unfavourably when compared with the world average of 2.6 beds as well as the capacity found in other emerging markets (2.3 beds in China and 1.8 beds in Brazil).

As in the US, bed statistics can be decomposed into licensed beds and staffed beds; the former represents potential capacity, while the latter reflects what the hospital can actually staff and utilize for patient treatment. Data from TechoPak suggest that 30 percent of private beds and 50 percent of public beds are “non-functional” due to lack of personnel. Using their base of 1.37 million beds, there are 853,000 operable beds in the country (consistent with the OECD bed/population ratio).

Overall, in spite of a majority of the population residing is rural areas, the distribution of hospital bed capacity is noticeably skewed in favour of urban India, where roughly three-quarters of both public- and private-sector beds are located. Nonetheless, even for many in close proximity to urban hospital facilities, “socioeconomic distance” has proven a barrier to healthcare access: basic measures of health for the poorest 40 percent of the urban population remain at par with the substandard levels observed in rural areas.