The Modern Hospital: Western Trends in Healthcare Facility Design from the 1980’s Onwards

Reinventing the Hospital

The old idea of one hospital to satisfy all needs is a thing of the past. We need a series of institutions. We’ll always need some healthcare factories for efficient, short-term, intensive-care stays, but we’ll need others where humanity won’t have to overcome the technical apparatus.

- John Thompson, 1976

Co-author of: The Hospital: A Social and Architectural History (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1975)

By 1980 in the USA, owing to various factors of change, cost containment had become the center of management’s focus. The healthcare marketplace assumed new importance in the overall scenario, and the smart players began to see architecture and interior design as a means of gaining an edge over the competition. If hospitals had previously been designed as “doctor’s workshops”, the providers now saw the emphasis being on amenities – the issue became one of attracting staff and patients through referrals and repeat visits. In short, it was a new ball game.

Postmodernism as a philosophy determining action was now embraced by the two reigning camps in the prevalent healthcare milieu, though approached from different viewpoints. The voluntary providers advocated patient-centered care and patient-centered facilities. The providers of healthcare concerned primarily with the business of healthcare realized that an attractive, inviting facility could have a positive impact on the bottom line. Both groups were shifting away from the traditional architecture of the modern hospital towards a more pluralistic approach.

These concerns, and their manifestation in built form, would dominate the period from 1980 till the end of the century.

There was a moving away from autonomous, highly centralized medical centers towards networks of providers in integrated delivery systems, often with a medical center remaining at the hub but with a greater focus on ambulatory care provided in off-site locations (the spokes). The hospital, as it had been known for the past 50 years, was picked apart, and the pieces redistributed. In this way, the hospital was subjected to a fundamental reappraisal and heightened scrutiny within and without the architectural profession, as a building type.

Verderber and Fine (see: bibliography) refer to this process as “functional deconstruction” to distinguish it from “Deconstructivism” as an architectural style, and define it as “a system-wide redistribution of services to community-based sites and the reconstitution of what would remain in the hospital ‘mothership’.”

They identify three simultaneous trends leading to this functional deconstruction, namely:

- Competition in the marketplace fueled by heightened expectations among healthcare consumers.

- The forces of cost containment owing to Medicaid and Medicare becoming the most costly federal entitlement programs, thus spurring the generation of new revenue producing services

- A postmodern ideology in architecture, and to some extent in health facility planning, calling for pluralism, in its ideal manifestation, of the most salient attributes of both the pre-modern and modern periods of architecture.

The Origins of Functional Deconstruction: The Megahospital

In 1983, in the USA, the federal government passed a bill that mandated the reimbursement of hospital inpatient services provided to Medicare and Medicaid according to “diagnosis-related groups” (DRGS). This system based on “capped” pricing categories instead of the previous fee-for-service system, provided the incentive for a hospital to contain costs – that is, to minimize the length of hospital stays, to avoid unnecessary services, and to treat many more people on an outpatient basis than ever before.

This pressurized hospitals to convert to a new mixture of inpatient and outpatient care.

The rise of ambulatory care and community –based care, DRGS, the new consumerism, and new medical technology all gave rise to a new wave of rethinking and master planning on the premise that an up-market facility would attract more patients and quality staff. The proliferation of health maintenance organizations (HMO’s) and preferred provider organizations (PPO’s) in the 1980’s also transformed the modern hospital. Capitated managed care soon became a formidable force in transforming the hospital from its traditional role as the option of first resort into the option of last resort in this new landscape.

These changes were, however, felt much sooner in the private sector; government built hospitals were far slower to adapt. In the largest institutions the influence of modernism persisted, although by 1980 many administrators realized that the dictum “bigger is better” no longer applied.

Walter Reed Army Medical Center, Washington D.C., 1980

Walter Reed Army Medical Center, Washington D.C., 1980

A large, late modernist example in the public sector was the first-stage Walter Reed Army Medical Center (1976 –1980) in Washington D.C., designed by Stone, Marracini and Patterson of San Francisco. The hospital was, from the exterior, little more than a highly centralized extruded functional planning diagram. Its austerity and clean lines were praised as a clear acknowledgement of the purity of modernism. The plans can be seen to be a reflection of the way in which functional planning activity diagrams in the form of abstractions were translated verbatim into floor plans, without any redeeming humane considerations being taken into account. In both the exterior and the interior this machine metaphor can be discerned. Natural daylighting is conspicuous by it’s absence.

Megahospitals were found to consume enormous amounts of energy, but this cost was justified by their creators on the grounds that other savings were being achieved. For this reason other megahospitals were built in the public sector.

High-Tech Romanticism

The megahospitals because of their immensity tended to overshadow another type of high-tech hospital. These hospitals were smaller in scale but no less expressive. The best of them extolled the virtues of high technology while making concessions to history, human scale, certain traditional planning concepts, and responses to landscape and local cultural determinants.

Mount Druitt Hospital, Sydney, Australia, 1978.

The Mount Druitt Hospital in Sydney, Australia (1976 – 1978), designed by Lawrence Neild was an interstitial community hospital configured as a side-by-side platform, with diagnostic, treatment, administrative and other support functions contiguous to but autonomous from the nursing wards. On the exterior a shiny steel-banded façade gave the building a ship-like appearance

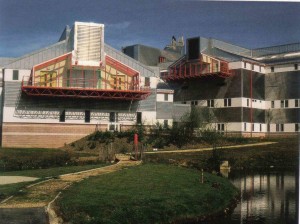

St. Mary’s Hospital, Isle of Wight, England, 1991.

St. Mary’s Hospital, Isle of Wight, England, 1991.

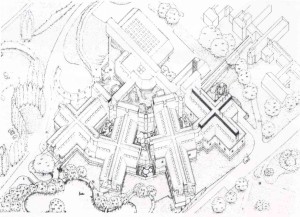

In England, a grand attempt to blend elements of the Nightingale hospital with the language of high-tech architecture occurred at Newport, on the Isle of Wight. St. Mary’s Hospital (1981 – 1991), designed by Ahrens, Burton, and Koralek, London, was a poetic synthesis of nineteenth- and late twentieth-century planning ideals. The architects aimed to create the antithesis of a modern block hospital – a romanticized notion of the hospital-in-a-park. Patient units were arrayed as four wings that radiated from a central support building and were connected at two points to each other. The main entrance has a tensile-structure canopy with expressed steel tubular framing. On the interior a modified interstitial system was employed whereby the service core was situated above the patient rooms in the center space of each wing, paralleling the circulation elements. This “floating” service zone was housed in the gabled roofs of the wings, which, from the exterior, contributed to a scaled-down neo-traditional quasi-residentialism fused with the vocabulary of high tech architecture.

St. Mary’s Hospital, Axonometric View

Functional Deconstruction and the Contemporary Hospital

By the 1990’s, the debate in theoretical architectural circles was not one of modernist versus postmodernist ideology but one of the merits of the transposition of deconstructivism and its legitimacy as the displacer of postmodernism. Deconstructivism, or theoretical deconstructivism was essentially a literary theory promulgated years earlier by theorists including Jacques Derrida and Roland Barthes. This philosophy was expropriated in the writings, and later the built work of Peter Eisenman, Bernard Tschumi, Frank Gehry, Zaha Hadid and Daniel Libeskind, among others. This avant-garde had focused its efforts on building types other than health care. The wheels of change turn slowly in the realm of institutional building types, and in health care facility architecture the effects of the new paradigmatic approaches in the twentieth century had been particularly slow to gain acceptance. This conservatism, when added to the preoccupations of the providers – the unbundling and redefinition of the outpatient community health clinic, ambulatory surgery centers, freestanding diagnostic clinic, mobile services and so on – gave rise not to an aesthetically driven expression of deconstructivism per se but to a functionally driven expression. Here, the constituent “parts of speech” were thrown out of equilibrium: departments and services were being re-conceptualized and recast, within and without. The hospital, by the late 1990’s subjected to widespread functional deconstruction of its internal components, was faced with downsizing to a flexible, less costly, yet more intensive rapid response entity, leading to dramatic changes in its scope and mission. In 1996, Lester B. Knight, a leading healthcare executive, remarked: “ It used to be that hospitals wanted to fill as many beds as possible, that’s how they made money. The incentive now is to keep beds empty. When the bed is empty the patient is not using up resources. That mentality change is a big change for the industry. It’s exciting to me.”

For the most part, healthcare architects were interested in the strategic planning (or organizational-spatial) nuances of this change in approach far more than any aesthetic ramifications of deconstruction, or, for that matter, post-modernism. Mainstream hospital planners listened passively to the “big picture” debates of their provider-clients and attempted to interpret optimum functionality through identifying the best room adjacencies, size, service mix, and layout of the hospital; these planners chose to remain indifferent (or at most neutral) to any large-scale rethinking of the core assumptions of their field.

Humanists with their focus on the architectural ramifications of patient-centered care would often reject classifications of their efforts as postmodern. By contrast, deconstruction, as a design language, was, according to its proponents, grounded in the dislocation of accepted formal relationships within buildings and in a questioning of deeper societal issues. To humanists this constituted a subversion of the nature of well-being; was it now to be appropriate for health architecture to express the chaos, inherent dislocational nature, and “discomfort” of contemporary culture and society rather than to promote health and wellness through a “comforting” architecture? Moreover, one might assume that the notion of a fully deconstructed health architecture, in both functional and formal-aesthetic terms, would be virtually antithetical to the notion of health architecture as a therapeutic, life-supportive modality.

Yale Psychiatric Institute, New Haven, Connecticut, 1990.

Regardless, an infinitesimal but influential fraction of the vast landscape of health architecture began to be influenced by the formal-aesthetic aspects of deconstruction. Perhaps the most well known example was the Yale Psychiatric Institute (1987 – 1990) in New Haven, by Frank Gehry. On a tight urban site, a replacement facility was designed as a campus composed of an assemblage of smaller parts that were skewed, twisted and distended to form a seemingly randomized, informal composition around a courtyard. When a post-occupancy evaluation was done, the building proved to work relatively well for the purpose for which it was initially designed.

Central Washington Hospital, Wenatchee, Washington, 1992

At the Central Washington Hospital (1989 – 92) in Wenatchee, Washington, by NBBJ Architects of Seattle, a series of brightly colored frontispiece architectural elements created a new image for the existing medical center. Various planes were pulled away from the main volume of the hospital and treated in different bright colors as distinct components – an arch, a porte cochere, a threshold – with perforations and projecting canopies evoking the spare minimalist work of Mexican architect Luis Barragan.

Would Yale Psychiatric and Central Washington serve as the bellwethers of a shift from a mainstream postmodern position to a tentative position of deconstruction in both functional and aesthetic terms? In each, the underlying organizational and aesthetic premise has been questioned, and although the purely functional aspects of each may not have been radically deconstructed, their aesthetic vocabularies provided some evidence of a search for balance between functional dislocation, aesthetic dislocation, and genuine therapeutic support.

Apart from issues of lifestyle, aesthetics, or their specific relation to the reconstituted healthcare facility, the field of healthcare architecture had not fostered a tradition of research. The scant prior research on user perception of the modern hospital had a discernible but minor impact, especially in comparison to the well funded financial, competitive and market analyses that had fueled the reshaping of the industry. In short, providers had routinely based costly, long-term facility related decisions on a subset of information, without systematic knowledge of consumer preferences and the effect of the healthcare environment on health and well-being. Hospital administrators and their mainstream healthcare firms instead sought commercial success in their institutions, and residentialism, the health mall and the grand atrium were often seized upon as the ideal attractors of business. And these amenities aptly projected the desired image of an open, caring, friendly environment, but was this enough? Many healthcare architects still considered it reckless to base design decisions on any terms other than “form follows function” – a credo that had guided hospital architects since Florence Nightingale.

Sociologist Robert Gutman has argued that the tendency of architects to be preoccupied with the external image has been a hindrance because it has tended to reduce the architect to the role of image-maker. A second, related concern has been the excessive willingness of architects to work in design teams, with the designer assigned the position of window dresser for the exterior of the building whose layout is essentially designed by health facility planners or by non-architectural professionals.

In 1980 the hospital was a highly centralized, relatively autonomous organizational and physical entity, but by the late 1990’s it had been subjected to a profound transformation. The pluralism in the type of healthcare facilities that proliferated in the last 15 years of the century was the result of four events that occurred at precisely the same time: a new freedom made possible by the rise of postmodernism, the acknowledged failure of the autonomous modern megahospital, new medical technologies permitting more services to be provided on an outpatient basis, and competitive pressures.

In the significantly downsized, transformed, and reconfigured hospital, designed to be re-christened the critical care center, core functions would remain, but by 2000 its patients were, on average, much sicker than those of 1980, not to mention those of 1965.

What will the survival of the hospital as we know it today, in India, depend on? We are all familiar with the buzzwords, “flexibility”, “adaptability”, “patient-friendly”…but how do we imbue into the built form the qualities necessary to make these words meaningful in anything more than a superficial way?

I think it demands the following knowledge, skills and sensitivity from the giver of this built form.

Firstly, working knowledge of the “functional” aspects of hospital design. In the real world of time and money constraints, the designer / design team cannot afford to research the subject from scratch.

Secondly, design maturity. Unlike mathematics and music, architecture boasts of no child prodigies.

Thirdly, sensitivity to (or an understanding of) oneself, other people, and the world around us. A healthcare facility designer, more than the designer of any other building type, needs a social conscience. As a profession, we need to care for the people, society and environment we are designing for / living in as much as any medical professional cares for his / her patient. We need to become your partners in healing.

On the shingle we hang out, we need to write “Healthcare Architect, M.D.” This is our path, the way we need to follow.

Source:Healthcare Architecture in an Era of Radical Transformation by Stephen Verderber and David J. Fine.

8 thoughts on “The Modern Hospital: Western Trends in Healthcare Facility Design from the 1980’s Onwards”