The Architecture of Health: Hospital Design and the Construction of Dignity

by

Michael P. Murphy Jr. with Jeffrey Mansfield and MASS Design Group

About The Authors

Michael Murphy, Int FRIBA, is the founding principal and executive director of MASS Design Group.

Jeffrey Manfield,is a design director at MASS Design Group and a JOHN W. Kluge Fellow at the Library of Congress.

MASS Design Group has been recognized as winner of the 2020 Architecture Innovator of the Year by the Wall Street Journal, the American Academy’s 2017 arts and Letters Award for Architecture, and the 2017 Cooper Hewitt National Design Award for Architecture.

About The Book

The Architecture of Health explores the past, present, and future of hospital design. A direct reflection of health care innovation through-out the ages, the hospital, as a design type, is locked in a struggle to predict and keep pace with the ever-evolving demands of medicine. Negotiating a fundamental conflict between form and function, hospital architecture may impede or advance our collective rights – such as the right to healthcare, and the right to breathe clean air – but it must fulfil our most elemental right: the right to dignity.

Praise for The Architecture of Health

“This important work is the first n memory to grant the theoretical heft this oft-overlooked building type deserves. As the designers of the most revolutionary and humane health acre architecture of recent decades, Murphy and MASS Design are the perfect fit to author this richly illustrated, vital volume for our pandemic age”

Sara Jensen Carr, author of The Topography of Wellness: How Health and Disease Shaped the American Landscape

“Murphy opens with an arresting premise – that the role of design is to ‘soften the blow’ of systems that are indifferent to our humanity. Seamlessly interweaving history, theory and practice, he models and powerfully conveys the opportunity to construct the health care systems we deserve.”

Neel Shah, MD, Assistant Professor, Harvard Medical school, and Chief Medical Officer, Maven Clinic

“’Where is the design?’ Murphy asks. Hospitals are always engineered, but they are seldom designed. In this indispensable book, Murphy scans history for traditional typologies and visionary innovations to highlight the need for all that great design can offer, committed to the full spectrum of needs and feelings that make us human. Respect and dignity above all.”

Paola Antonelli, Senior Curator of Architecture and Design and Director of Research and Development, the Museum of Modern Art, New York

“This book is about how to make today’s hospitals safe, dignified, and beautiful, but it also takes up the history of the idea of a hospital – and thus hospitality itself. It’s reassuring knowing that today’s most ambitious architects and designers are familiar with what succeeded and what failed, and why.”

Paul Farmer, MD, Kolokotrones University Professor and Chair, department of Global Health and Social Medicine, Harvard Medical School

Preface

Since March of 2020, when the number of COVID-19 cases rose exponentially around the globe, discussions of hospital design have become increasingly charged and complex. The virus was the catalyst, but the debate is indicative of larger issues. As the pandemic revealed embedded inequities in public health, hospitals as spaces of care – and spaces of dignity – have found themselves more and more in the spotlight. Rightfully so, as medical professionals have transformed into essential workers, and – as we anticipate further disruptions in the form of pandemics and climate related crises – our hospitals continue to reflect social values and commitments. The Architecture of Health enters into this charged space, describing the formal templates and organizational patterns of hospital design over the centuries, but keeping us tightly focused on the importance of these institutions to upholding and reaffirming the values of democratic, equitable societies. We will weather the coming storms according to the strength of our health facilities.

And storms are coming. From an architectural perspective, one of the essential challenges introduced, or exacerbated, by COVID-19 is the politicization of ventilation. In hospitals and schools in particular, the transmission of an aerosol virus may be reduced by increasing the volume of outside air that enters the space. Moving more air around leads to a greater demand on heating, ventilation and air-conditioning systems and thus, within the existing electrical grid, to increasing carbon emissions. In other words, mitigating the life-threatening effects of one public health crisis – the pandemic – exacerbates the near- and long term effects of another – the climatic instabilities wrought by global warming.

The Architecture of Health is thus unrelenting on what might at first seem to be a secondary aspect of hospital design: the effective management of air. In chapter 2, author Michael Murphy quotes Florence Nightingale: “The very first canon of nursing…is this: to keep the air (the patient) breathes as pure as the external air.” This may seem anachronistic, in that the very air surrounding many of today’s urban hospitals is often more toxic than would be preferred, but the premise remains: one of the primary tasks of hospital design is the provision of breathable air, of an interior atmosphere conducive to health and well-being. Today, this entails filtering, ventilating, and conditioning air; indeed “air-conditioning, in the literal sense, will establish itself as the main space-political theme of the coming era,” the philosopher and cultural theorist Peter Sloterdijk wrote in 2014, in the second volume of his Spheres trilogy. Their will be battles over air, in other words, debates about the value of a healthy environment. Hospitals will be – are already – at the centre of these debates.

This book traces an essential historical arc: from open pavilion hospital to the closed, air-conditioned block and, perhaps, back again. For as societies begin to attend more aggressively to a very limited carbon budget, hospitals will remain one of the few places that air-conditioning is warranted: some amount of fossil-fueled ventilation or thermal isolation is likely to remain necessary for the provision of dignifying care. Murphy clarifies that the design of hospitals will increasingly involve debates around the right to breathe: in the hospital, breath is valued above all else.

But who gets to breathe? The challenge of hospital design is to maintain a space of atmospheric exclusivity that is nonetheless available to all. The Architecture of Health helps us to see that our current health care spaces are a legacy of colonial and postcolonial regimes of population management. The hospital was born, at least in part, not from an impulse of care but from the necessities of war and the desire to optimize an oppressed workforce – that is, through the same calculation of use value that are evident in the baroque mystifications of contemporary insurance regimes. Lives are, to some, numbers. Murphy’s careful analysis encourages an approach to spaces of care that resists this legacy, demonstrating that we might learn the lessons of operational and atmospheric management while refusing the depersonalization of the human body; we might refuse to see public health as an agent of economic and racial stratification.

Indeed, to design dignifying spaces is to affirm and encourage a respect for all bodies, all souls, equally. The Architecture of Health is in this sense itself a breath of fresh air, insisting that architects recognize the importance of the hospital as a space of dignity – a provision that will challenge both existing and newly built spaces, and that will be increasingly difficult to achieve though ever more necessary to maintain in coming decades.

Daniel A. Barber

Associate Professor of Architecture

Waltzman School of Design, University of Pennsylvania

Prologue: Consider the Hospital

At some point, facing tragedy or joy, most of us will spend days, if not weeks, in a hospital, coping with the existential realities of birth and death. When I was a young architecture student, I sat with my father as he lay in a Manhattan hospital near the end of his life. I was shocked to see how few of the design lessons I was taught to honour had made their way into the spaces of care. As equipment beeped and blinked, I asked myself, what has made this place so indifferent to the human experience? Why the indignity? Where is the design?

Later, I faced the flip side of this challenge, as part of a team designing a hospital for epidemic disease in Butaro, a remote district of Rwanda. Modern mechanical systems were too costly to purchase and maintain, and so we looked back at historical medical facilities for strategies to manage the movement of air, waste and water. That research exposed me to a history of buildings and to foundational contradictions involved in the design of spaces that serve both the public and the individual. Looking back at that time spent with my father, I reflected that his hospital provided care that few in the world can access: not only leading science but also restorative moments, like the view of the East river from his double room. But the hallways filled with beeping equipment, the windowless waiting room, the maze-like sequence from street to patient room, the sense of being lost in the institution – those experiences will never leave me. My father’s hospital journey probably served both his humanity and his medical condition, but rarely at the same time. The role of design is to manage this conflict. It softens the blow of our irrelevance to the systems around us, reminding us that we still matter. My friend and mentor Dr. Paul Framer has called this “dignity construction” and the search for it in architecture is the purpose of this book.

The history of hospitals is not merely an account of changes in style, form and auteur. Instead, it is a lineage of buildings that were designed to shape social conditions for others, that represented key milestones in political eras, and that were composed as systems by many authors. It includes brilliant and visionary creators – hospital architects, but also systems designers – driven by the aim of social change. They found innovative ways to resolve the medical dilemmas of their eras, and at times they also discovered universal truths. They acknowledged that a hospital is the visible manifestation of a vast network of services, politics and people. The characters in this book are all polymaths and provocateurs, but probably none is quite as essential as Florence Nightingale, who, in laying out her guidelines for hospital design in 1859, demonstrated that the architecture of a medical facility can influence an entire political and social order. She showed us why buildings matter.

Hospital architecture illustrates the contradiction inherent in nearly all public built spaces: the tension between an imagined population that will need public services – charity – and the systems overt need to shape that public’s behaviour so its members may attain it – control. The principles of charity and control pertain to architecture more broadly, but they were birthed in the clinic, and they can never be disentangled from the spaces of medical treatment. They help shape our understanding of architecture ambivalence toward it’s public role and clarify that – whether we acknowledge it or not – buildings can determine our behaviour as individuals and advance our right as members of a society.

Michael P. Murphy Jr.

Epilogue: The Right to Breathe

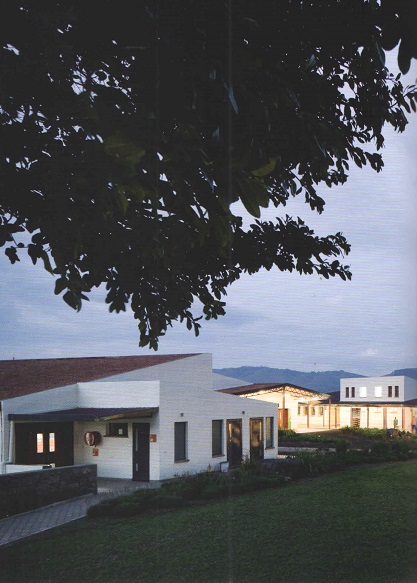

Butaro District Hospital, Rwanda

In 2008, Rwanda was freshly tilled soil. Streets were swept, lawns were manicured, and education and health care were guaranteed. The genocide of 1994 had stripped people of dignity and destroyed a generation of lives; the country had seen the depths to which humanity could fall. But fourteen years later, after focused investments in health, education, housing, economic reconstruction, and reconciliation, Rwanda was abundant and hopeful. It was shedding histories of colonialism and ethnic division and recalibrating its future towards shared economic and social progress. To assist in strengthening the country’s health care system, dr. Paul framer and his organization Partners in Health were asked by the Rwandan government to consult. After two decades of providing visionary medical health services to the world’s most underserved communities, Partners In Health had shown that health care systems could be designed to meet patients where they are. A key element of the collaboration between the Rwandan government and Partners In Health would be a new purpose-built hospital in the remote northern hamlet of Butaro.

At that time, I was studying architecture. After hearing Farmer lecture, I asked him which architects he was working with and how I might be of service. He told me that few had ever reached out to him, and his organization was often left to design and build by itself, with just the resources it already had. He described the failure of “Western” experts as a remnant of colonial power. Outside designers working on projects for the underserved, he said, were intoxicated by modern emergency services in shipping containers. They never stopped to ask if people wanted to receive health care in an industrial waste product.

He also described the dystopia created by modern technology, with its ostensibly cheap, easily deployable medical care, panacea solutions to drinking water, and procedural hacks. He called this equipment “junk for the poor” and described it filling storage closets, sitting broken in hallways, or lingering, inoperable, in medical clinics the world over. There is no one-size-fits-all solution to the health care problems of the poor, he said. To deliver health care was to “accompany” the community and listen to its needs, serving the system from within instead of designing from outside.

Farmer’s lead engineer in Rwanda, Bruce Nizeye, needed help designing the hospital in Butaro, and he invited me to join him there in 2008. I jumped at the chance. Most of the clinics and hospitals Partners In Health had previously built were additions or renovations to hospital campuses. The Butaro hospital was, at the time. The largest project it had ever designed and constructed from the ground up. The client was the government of Rwanda, and the hospital needed to address current problems, such as the epidemic of tuberculosis that was ravaging poor communities around the globe.

Dr. Michael Rich, an expert on tuberculosis and its multidrug-resistant variants, was then the director of Partners In Health’s Rwanda operations (through its sister organization Inshuti Mu Buzima) and an architecture junkie. Hospital hallways, he explained, were the major problem in the transmission of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis. Patients waiting in these spaces without windows or airflow would cough on each other, become co-infected with drug-resistant variants, and then bring them back to their communities. In the hallways of hospitals, buildings meant to heal, the epidemic had begun.

“we have been trying to design hallways out of hospitals for years,” Rich told me. Naively, I asked, “Shouldn’t a modern hospital use a mechanical system to ventilate its spaces?” Like a patient teacher, he explained that mechanical systems never work as designed. And sometimes, he said, they are too expensive to maintain. When they break or are turned off for budgetary reasons, the spaces have worse airflow than those with simple windows or outdoor waiting areas. Better mechanical systems do not meet patients where they are.

Dr. Edward Nardell, another tuberculosis expert at Partners In Health, pointed me to a study in Peru that showed how older, colonial buildings, built with generous windows, tall ceilings, and open-air waiting areas, were better able to prevent the transmission of tuberculosis than newer ones designed to keep mechanically conditioned air from leaking out. Nardell also introduced me to Florence Nightingales Notes on Hospitals (1859) and her spatial strategies to increase airflow and reduce disease transmission, and I realized that there were universal principles of building function that transcend culture, context, and time. We sought to locate more of these truths and insert them into the design of the Butaro hospital.

The Right to Breathe

We took Rich at his word, and proposed a hospital without hallways. In the new structure, all patient, staff, and public movement and waiting takes place outdoors. Rwanda’s temperate climate allows for comfortable exterior waiting throughout most of the year, but when it rains, covered outdoor areas provide respite. When it gets cold, we should fetch blankets, Farmer said, unknowingly replicating a lesson from both the Paimo Sanatorium and the Peter Brent Brigham Hospital in Boston during the influenza pandemic of 1918. Exterior hallways necessitated a distributed multi-building design rather than a centrally loaded institution, and the buildings had to be thin (so air could move through them). Doctors would walk between buildings dispersed in a campus setting, so we created covered pathways surrounded by lush landscaping and gardens to brighten their journey.

Elevators often break, and in rural areas the maintenance required is too specific for proper upkeep. We needed a facility that would be accessible without elevators, one that a patient in a wheelchair could fully traverse. Rwanda’s zigzagging hillside footpaths were a useful precedent; we alyered the hospital across the crest of a hill to ensure that multiple stories would be accessible at ground level. This had the additional benefit of leaving space for future campus growth.

The trend in both infection control and patient experience was to isolate patients in single rooms. But in rural settings, Rich told me, patients were dying more often in isolated rooms because there were not enough staff to monitor them. Nurses had to see the patients, and patients had to see the nurses: there was a reciprocal relationship of care and trust. Without complicated monitoring devices, it was necessary to have a visual relationship between the nurses’ station and the patient. This was less a form of control or dominance, we learned, than a way of ensuring everyone was attentive to the needs of the patient. We designed open wards with the nurses’ stations in the centre, low walls to ensure the visibility of the entire room and all the beds, and few corners to block the view between staff and patient. Glass-doored isolation rooms for actively contagious patients are located at the end of each ward. Adjacent bathrooms are equipped with their own venting and entrances off the wards to reduce the spread of odours and bio-aerosols.

Nightingales prescriptions, I learned, defined a parametric relationship between people, spaces, and services. When one of those elements is out of balance, the systems can break down and patients get sicker. To target overcrowding, we amended the nightingale ward slightly, replacing the central hallway with a half-height wall. Patient beds project out from this central wall, facing the windows, and the pathway encircles the wards rather than cutting through the centre of it. This provides three complementary benefits. First, with an immovable wall in the centre and smaller hallways on the perimeter, staff can’t overfill the ward without disrupting the nursing rounds. In this way, we designed against the downside of flexibility. Second, this central wall consolidates electrical outlets, call buttons and oxygen sockets, which are placed in the headboard. Its coloured panels are removable to allow for the addition of future systems and for repair.

The third benefit taught me about the deeper role of architecture. With their beds oriented to face the windows, patients can see the breathtaking landscape outside. Scholarship has shown that a simple view reduces patient stay times and pain medication requests. Plus, it was quite obvious that it would be preferable to look out a window rather than gaze at a roomful of other sick people. With beds no longer ranged around the periphery of the ward, we were able to increase the window sizes, lowering the sill below headboard height, and thus bring more light, views, and air into the space. This sinle move demonstrated that when architectural design is human centered, it can be in harmony with function, form, and experience.

“With limited resources,” Farmer once said to me, “people get resourceful.” This seemed to be the case in Butaro. The new ward design, now called the Butaro ward, is written into national guidelines, and it has been replicated in hospitals throughout Rwanda and beyond. I am sure we will see the Butaro ward adjust and recalibrate as new services and systems take over these hospitals. But I was reminded that when doctors fight for their patients access to health care, they are also fighting for their right to breathe clean, uncontaminated air. Nightingale changed a lot of things, but most important to us was the revelation that architecture is an essential, rights-based discipline. I learned this on that hill in Rwanda.

Constructing Dignity

Designing the Butaro hospital was not without difficulties. My colleague David Saladik and I lived in Butaro in a district building that had housed a prison cell during the genocide. Our colleagues Alan ricks, Sierra Bainbridge, and others were working remotely and sending iterations over an unstable internet connection. We drew all day and then presented the plans and ideas to the doctors at night. The budget was incredibly tight and the timeline was even tighter, and so many ideas had to be rethought. And not all the stakeholders welcomed a young design team taking up crucial space in this hospital far in the hinterlands of northern Rwanda. One prominent visiting doctor asked, “Aren’t more equipment and more beds a better investment than fancy buildings?” scarce resources require sacrifices, he seemed to suggest. He was a surgeon working in field hospitals, and perhaps this equation made sense in his work and saved lives. Or was he repeating that adage by Marc-Antoine Laugier, that “houses designed to lodge poor people ought to taste something of it….The poor should be lodged as poor.”? In either case, I could sympathize with his suspicion. Until they were built, our proposals were just empty ideas worth investing in – including our proposal to clad the entire campus in volcanic rock harvested from the surrounding hills.

Many houses and garden walls in that region of Rwanda are built from basalt, a volcanic – the result of eruptions of lava – that is found between layers of soil in the ground. Butaro is in the foothills of the Virunga mountain chain, and this black porous rock similar to pumice is a perfect building material, soft and very malleable. Local homes made from the basalt feature thick mortar joints and sometimes hand-applied cement over the stone, creating a polka-dot pattern. We wanted the hospital cladding to look more like the garden walls, which were dry stacked with no visible signs of mortar, high-lighting their texture and the fact that the materials came from this very ground. To fit the stones together in this way, like a jigsaw puzzle, required both innovation and a high level of skill.

Nizeye, the lead engineer and builder, insisted that we make a number of mock-ups, and hired the best masons he could find to assemble various iterations. We got to the mock-ups late at night; it was pitch black, but construction had to start in the morning. We beamed car headlights on the samples and perused our options. Some had too much mortar, and the stones in others were too uniform. The last mock-up was perfect, a puzzle of rock well configured into unique shapes, with tight joints that showed very little mortar. Our choice was made.

The next morning, the masons got to work. One of them, Anne Marie Nyiranshimiyimana, had started a guild of female masons; she made the two-hour journey from her home to show off their skills. Emmanuel (Hakiza) Hakizama was training as a mason at the time. They and their colleagues began covering the walls of the hospital, including the first main building, which houses the outpatient waiting areas, laboratory, pharmacy, and operating room sequence areas. This building is the largest, and the one first encountered by the patients: it had to be right.

When the masons began their work, the stones looked great assembled on top of each other. Minor variations in joint sizes would disappear in the image of a massive stone wall, I thought. But slowly, as the weeks went by, their calibration got tighter, the joints narrower, and the stones more unique. One mason developed a method of bending a clothes hanger to approximate the shape of the stone they needed to fit too next. Their speed picked up, as did their precision, and the massive, nearly thirty-foot foundation wall began to tower over the campus. By the time Hakizama, Nyiranshimiyimana, and their teams worked their way round to the entrance corner where they had started, there was a noticeable difference in quality between where they and begun and where they ended. The masonry team asked if they could take down the original corner and rebuild it so it matched more precisely, and although it caused a small delay, Nizeye agreed.

Local artisans assembled every piece of the hospital, from the walls to the furniture to the windows, and the result is a total work of art. This hospital is greater than the individuals who worked on it; it is a symbol that transmits purpose and attention. This has nothing to do with the subjective debates about form and sculpture I weathered in school. Nor is it misplaced “sumptuousness” or “magnificence” Laugier warned us about. It is, rather the formation of the most foundational architectural element – the wall – from the original tools of construction: the hand and the stone. This I realized, was the composition of beauty.

A year after the hospital opened, the sceptical field surgeon cornered me at an event. “I thought what you were doing was an enormous waste of time time and resources, “ he admitted. “We doctors look for proof and evidence; it is hard to quantify the value of design. But when I saw the stone walls, I realized we needed this too. The unquantifiable, the beautiful, is in the service of our patients and our beliefs.”

On that hilltop in Rwanda, Nizeye, the stone masons, and that doctor taught me something I had not learned in architecture school. They taught me that architecture can both impede and advance our collective rights – such as the right to health acre or the right to breathe. But they also taught me that buildings, made with great care, can help us locate ourselves within the sometimes dizzying and alienating pressures of the world around us. They locate and ground us, and through this they give us hope. Buildings can fulfil our most elemental right – the right to dignity.

0 thoughts on “The Architecture of Health: Hospital Design and the Construction of Dignity”