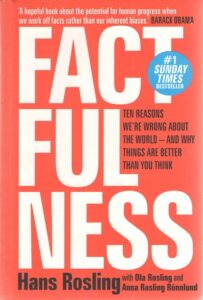

Factfulness: Ten Reasons We’re Wrong About The World – And Why Things Are Better Than You Think

by

Hans Rosling with Ola Rosling and Anna Rosling Ronnlund

About The Author

Hans Rosling was a medical doctor, professor of international health, and renowned public educator. He was an adviser to the World Health Organization and UNICEF, and he co-founded Medicins Sans Frontiers in Sweden and the Gapminder Foundation. His TED talks have been viewed more than thirty-five million times, and he was listed as one of Time magazine’s one hundred most influential people in the world. Hans died in 2017, having devoted the last years of his life to writing this book.

Ola Rosling and Anna Rosling Ronnlund, Hans’s son and daughter-in-law, are co-founders of the Gapminder Foundation, and Ola its director from 2005 to 2007 and from 2010 to the present day. After Google Trendanalyzer, the bubblechart tool invented and designed by Anna and Ola, Ola became head of Google’s Public Data Team and Anna became the team’s senior user-experience (UX) designer. They have both received international awards for their work.

About The Book

FACTFULNESS: the stress-reducing habit of only carrying opinions for which you have strong supporting facts.

When asked simple questions about global trends – what percentage of people around the world are living in poverty; why the global population is increasing; how many girls finish school – we systematically get the answers wrong. So wrong that a chimpanzee choosing answers at random will consistently outguess journalist, Nobel laureates, and investment bankers.

In Factfulness, Professor of International Health and global TED phenomenon Hans Rosling, together with his two long-time collaborators Anna and Ola, offers a radical new explanation of why this happens, and reveals the ten instincts that distort our perspective.

It turns out that the world, for all its imperfections, is in a much better state than we might think. But when we worry about everything all the time instead of embracing a world view based on facts, we can lose our ability to focus on the things that threaten us most.

Inspiring and revelatory, filled with lively anecdotes and moving stories, Factfulness is an urgent and essential book that will change the way you see the world.

Praise for The Nature of Design

“A hopeful book about the potential for human progress when we work off facts rather than our inherent biases.”

Barack Obama

“Superb…an inspiration.”

Tim Harford

“One of the most important books I’ve ever read – an indispensable guide to thinking clearly about the world.”

Bill Gates

“Hans Rosling tells the story of “the secret silent miracle of human progress” as only he can. But Factfulness does more than that. It also explains why progress is so often secret and silent and teaches readers how to see it clearly”

Melinda Gates

The Five Global Risks We Should Worry About

I do not deny that there are pressing global risks we need to address. I am not an optimist painting the world in pink. I don’t get calm by looking away from problems. The five that concern me most are the risks of global pandemic, financial collapse, world war, climate change, and extreme poverty. Why is it these problems that cause me most concern? Because they are quite likely to happen: the first three have all happened before and the other two are happening now; and because each has the potential to cause mass suffering either directly or indirectly by pausing human progress for many years or decades. If we fail here, nothing else will work. These are mega killers that we must avoid, if at all possible, by acting collaboratively and step-by-step.

I do not deny that there are pressing global risks we need to address. I am not an optimist painting the world in pink. I don’t get calm by looking away from problems. The five that concern me most are the risks of global pandemic, financial collapse, world war, climate change, and extreme poverty. Why is it these problems that cause me most concern? Because they are quite likely to happen: the first three have all happened before and the other two are happening now; and because each has the potential to cause mass suffering either directly or indirectly by pausing human progress for many years or decades. If we fail here, nothing else will work. These are mega killers that we must avoid, if at all possible, by acting collaboratively and step-by-step.

(There is a sixth candidate for this list. It is the unknown risk. It is the probability that something we have not even thought of will cause terrible suffering and devastation. That is a sobering thought. While it is truly pointless worrying about something unknown that we can do nothing about, we must also stay curious and alert to new risks, so that we can respond to them.)

Global Pandemic

The Spanish flu that spread across the world in the wake of the First World War killed 50 million people – more people than the war had, although that was because the populations were already weakened after four years of war. As a result, global life expectancy fell by ten years, from 33 to 23, as you can see from the dip in the curve on page 55. Serious experts on infectious diseases agree that a new nasty kind of flu is still the most dangerous threat to global health. The reason: flu’s transmission route. It flies through the air on tiny droplets. A person can enter a subway car and infect everyone in it without them touching each other, or even touching the same spot. An airborne disease like flu, with the ability to spread very fast, constitutes a greater threat to humanity than diseases like Ebola or HIV/AIDS. Protecting ourselves in every possible way from a virus that is highly transmissible and ignores every type of defence is worth the effort, to put it mildly.

The Spanish flu that spread across the world in the wake of the First World War killed 50 million people – more people than the war had, although that was because the populations were already weakened after four years of war. As a result, global life expectancy fell by ten years, from 33 to 23, as you can see from the dip in the curve on page 55. Serious experts on infectious diseases agree that a new nasty kind of flu is still the most dangerous threat to global health. The reason: flu’s transmission route. It flies through the air on tiny droplets. A person can enter a subway car and infect everyone in it without them touching each other, or even touching the same spot. An airborne disease like flu, with the ability to spread very fast, constitutes a greater threat to humanity than diseases like Ebola or HIV/AIDS. Protecting ourselves in every possible way from a virus that is highly transmissible and ignores every type of defence is worth the effort, to put it mildly.

The world is more ready to deal with flu than it has been in the past, but people on Level 1 still live in societies where it can be difficult to intervene rapidly against an aggressively spreading disease. We need to ensure that basic health care reaches everyone, everywhere, so that outbreaks can be discovered more quickly. And we need the World Health Organization to remain healthy and strong to coordinate a global response.

Financial Collapse

In a globalized world, the consequences of financial bubbles are devastating. They can crash the economies of entire countries and put huge numbers of people out of work, creating disgruntled citizens looking for radical solutions. A really large bank collapse would be way worse than the global eruption that started with the US housing loan crash in 2008. It could crash the entire global economy.

In a globalized world, the consequences of financial bubbles are devastating. They can crash the economies of entire countries and put huge numbers of people out of work, creating disgruntled citizens looking for radical solutions. A really large bank collapse would be way worse than the global eruption that started with the US housing loan crash in 2008. It could crash the entire global economy.

Since even the best economists in the world failed to predict the last crash and fail year on year to predict the recovery from it – because the system is too complicated for accurate predictions – there is no reason to suppose that because no one is predicting a crash, it will not happen. If we had a simpler system there might be some chance of understanding it and working out how to avoid future

collapses.

World War III

My whole life I have done all I can to establish relations with people in other countries and cultures. It’s not only fun but also necessary to strengthen the global safety net against the terrible human instinct for violent retaliation and the worst evil of all: war.

We need Olympic Games, international trade, educational exchange programs, free internet – anything that lets us meet across ethnic groups and country borders. We must take care of and strengthen our safety nets for world peace. Without world peace, none of our sustainability goals will be achievable. It’s a hue diplomatic challenge to prevent the proud and nostalgic nations with a violent track record from attacking others now that they are losing their grip on the world market. We must help the old West to find a new way to integrate itself peacefully into the new world.

Climate Change

It is not necessary to look only at the worst-case scenario to see that climate change poses an enormous threat. The planet’s common resources, like the atmosphere, can only be governed by a globally respected authority, in a peaceful world abiding by global standards.

It is not necessary to look only at the worst-case scenario to see that climate change poses an enormous threat. The planet’s common resources, like the atmosphere, can only be governed by a globally respected authority, in a peaceful world abiding by global standards.

This can be done: we did it already with ozone depleters and with lead in gasoline, both of which the world community reduced to almost zero in two decades. It requires a strong, well-functioning international community (to be clear, I am talking about the UN). And it requires some sense of global solidarity towards the needs of different people on different income levels. The global community cannot claim such solidarity if it talks about denying the 1 billion people on Level 1 access to electricity, which would add almost nothing to global emissions. The richest countries emit by far the most CO2 and must start improving first before wasting time pressuring others.

Extreme Poverty

The other risks I have mentioned are highly probable scenarios that would bring unknown levels of future suffering. Extreme poverty isn’t really a risk. The suffering it causes is not unknown, and not in the future. It’s a reality. It’s misery, day to day, right now. It is also where Ebola outbreaks come from, because there are no health services to encounter them at an early stage; and where civil wars start, because young men desperate for food and work, and with nothing to lose, tend to be more willing to join brutal guerrilla movements. It’s a vicious circle: poverty leads to civil war, and civil war leads to poverty. When rhinos are stuck in the middle of a civil war, it’s much more difficult to save them.

Today, a period of relative world peace has enabled a growing world prosperity. A smaller proportion of people than ever before is stuck in extreme poverty. But there are still 800 million people left. Unlike with climate change, we don’t need predictions and scenarios. We know that 800 million are suffering right now. We also know the solutions: peace, schooling, universal basic health care, electricity, clean water, toilets, contraceptives, and microcredits to get market forces started. There’s no innovation needed to end poverty. It’s all about walking the last mile with what’s worked everywhere else. And we know that the quicker we act, the smaller the problem, because as long as people live in extreme poverty they keep having large families and there numbers keep increasing. Providing these necessities of a decent life, quickly, to the final billion, is a clear, fact-based priority.

Today, a period of relative world peace has enabled a growing world prosperity. A smaller proportion of people than ever before is stuck in extreme poverty. But there are still 800 million people left. Unlike with climate change, we don’t need predictions and scenarios. We know that 800 million are suffering right now. We also know the solutions: peace, schooling, universal basic health care, electricity, clean water, toilets, contraceptives, and microcredits to get market forces started. There’s no innovation needed to end poverty. It’s all about walking the last mile with what’s worked everywhere else. And we know that the quicker we act, the smaller the problem, because as long as people live in extreme poverty they keep having large families and there numbers keep increasing. Providing these necessities of a decent life, quickly, to the final billion, is a clear, fact-based priority.

The hardest to help will be those stuck behind violent and chaotic armed gangs in weakly governed states. To escape poverty, they will need a stabilizing military presence of some kind. They will need police officers with guns and government authority to defend innocent citizens against violence and to allow teachers to educate the next generation in peace.

Still I’m possibilistic. The next generation is like the last runner in a very long relay race. The race to end extreme poverty has been a marathon, with the starter gun fired in 1800. The next generation has the unique opportunity to complete the job: to pick up the baton, cross the line, and raise its hands in triumph. The project must be completed. And we should have a big party when we are done.

Still I’m possibilistic. The next generation is like the last runner in a very long relay race. The race to end extreme poverty has been a marathon, with the starter gun fired in 1800. The next generation has the unique opportunity to complete the job: to pick up the baton, cross the line, and raise its hands in triumph. The project must be completed. And we should have a big party when we are done.

Knowing that some things are enormously important is, for me, relaxing. These five big risks are where we must direct our energy. These risks need to be approached with cool heads and robust, independent data. These risks require global collaboration and global resourcing. These risks should be approached through baby steps and constant evaluation, not through drastic actions. These risks should be respected by all activists, in all causes. These risks are too big for us to cry wolf.

I don’t tell you not to worry. I tell you to worry about the right things. I don’t tell you to look away from the news or ignore the activists’ call to action. I tell you to ignore the noise, but keep an eye on the big global risks. I don’t tell you not to be afraid. I tell you to stay coolheaded and support the global collaborations we need to reduce these risks. Be less stressed by the imaginary problems of an overdramatic world, and be more alert to the real problems and how to solve them.

Why I want to stop talking about the “developing world.

Factfulness is one of the most educational books I’ve ever read.

By Bill Gates

I talk about the developed and developing world all the time, but I shouldn’t.

My late friend Hans Rosling called the labels “outdated” and “meaningless.” Any categorization that lumps together China and the Democratic Republic of Congo is too broad to be useful. But I’ve continued to use “developed” and “developing” in public (and on this blog) because there wasn’t a more accurate, easily understandable alternative—until now.

My late friend Hans Rosling called the labels “outdated” and “meaningless.” Any categorization that lumps together China and the Democratic Republic of Congo is too broad to be useful. But I’ve continued to use “developed” and “developing” in public (and on this blog) because there wasn’t a more accurate, easily understandable alternative—until now.

I recently read Hans’ new book Factfulness: Ten Reasons We’re Wrong About the World—and Why Things Are Better Than You Think. In it, he offers a new framework for how to think about the world. Hans proposes four income groups (with the largest number of people living on level 2):

One billion people live on level 1. This is what we think of as extreme poverty. If you’re on level 1, you survive on less than $2 a day and get around by walking barefoot. Your food is cooked over an open fire, and you spend most of your day traveling to fetch water. At night, you and your children sleep on a dirt floor.

This was a breakthrough to me. The framework Hans enunciates is one that took me decades of working in global development to create for myself, and I could have never expressed it in such a clear way. I’m going to try to use this model moving forward.

This was a breakthrough to me. The framework Hans enunciates is one that took me decades of working in global development to create for myself, and I could have never expressed it in such a clear way. I’m going to try to use this model moving forward.

Why does it matter? It’s hard to pick up on progress if you divide the world into rich countries and poor countries. When those are the only two options, you’re more likely to think anyone who doesn’t have a certain quality of life is “poor.”

Hans compares this instinct to standing on top of a skyscraper and looking down at a city. All of the other buildings will look short to you whether they’re ten stories or 50 stories high. It’s the same with income. Life is significantly better for those on level 2 than level 1, but it’s hard to see that from level 4 unless you know to look for it.

The four levels are just one of many insights in Factfulness that will help you better understand the world. I’m excited that Hans’ publisher Flatiron Books plans to donate 5,000 copies to Books for Africa and Reader to Reader—two organizations that encourage reading in underserved communities. Hans worked on the book until his last days (even bringing several chapters with him in the ambulance to the hospital), and his son Ola and daughter-in-law Anna helped finish it after he passed.

The bulk of the book is devoted to ten instincts that keep us from seeing the world factfully. These range from the fear instinct (we pay more attention to scary things) to the size instinct (standalone numbers often look more impressive than they really are) to the gap instinct (most people fall between two extremes). With each one, he offers practical advice about how to overcome our innate biases.

The bulk of the book is devoted to ten instincts that keep us from seeing the world factfully. These range from the fear instinct (we pay more attention to scary things) to the size instinct (standalone numbers often look more impressive than they really are) to the gap instinct (most people fall between two extremes). With each one, he offers practical advice about how to overcome our innate biases.

Hans argues that these instincts make it difficult to put events in perspective. Imagine news coverage about a natural disaster—say, a tornado that kills 10 people in a small town. If you look at only the headlines, you’ll view the event as an unbearable tragedy (which it is). But if you put it in the context of history, you’ll also know that tornadoes today are a lot less deadly than they used to be, thanks to advanced warning systems. That’s no consolation to the loved ones of those who died, but it matters a great deal to everyone who survived the tornado.

In other words, the world can be both bad and better. That idea drives the work Melinda and I do every day, and Hans articulates it beautifully in Factfulness. It’s a great companion to Steven Pinker’s

Enlightenment Now (although Hans is a little less academic than Pinker is). With rare exceptions, most of the miracles of humankind are long-term, constructed things. Progress comes bit by bit. We’ve cut the number of people living in extreme poverty by half over the last twenty years, but there was never a morning when “POVERTY RATES DROP INCREMENTALLY” dominated newspaper headlines.

Another remarkable thing about Factfulness—and about Hans himself—is that he refuses to judge anyone for their misconceptions. Most writers would beat people up for their ignorance, but he doesn’t. Hans even resists going after the media. Instead, he tells you about the history of his own ignorance. He explains that these instincts make us human, and that overcoming them isn’t easy.

Another remarkable thing about Factfulness—and about Hans himself—is that he refuses to judge anyone for their misconceptions. Most writers would beat people up for their ignorance, but he doesn’t. Hans even resists going after the media. Instead, he tells you about the history of his own ignorance. He explains that these instincts make us human, and that overcoming them isn’t easy.

That’s classic Hans. He was always kind, often patient, and never judgmental. He spent his life not only understanding how global health was improving but sharing what he learned in a fun, clear way with a broad set of people. If you never met Hans or watched one of his many TED talks, Factfulness will help you get a sense of why he was so special. I wish I could tell Hans how much I liked it. Factfulness is a fantastic book, and I hope a lot of people read it.

Factfulness review: The miracle of human progress

Uma Mahadevan-Dasgupta-The Hindu

Is a tendency towards negativity, fear and blame preventing us from seeing all the good in the world?

Is a tendency towards negativity, fear and blame preventing us from seeing all the good in the world?

As district medical officer in Mozambique, Hans Rosling discovered a previously unknown paralytic disease. Later, he became a professor of international health, co-founded Médecins Sans Frontières in Sweden, and a renowned public educator. His TED talks have been viewed over 35 million times.

Rosling was also a sword swallower, having learned the skill from a patient. Often, he would do a small show at the end of a lecture: “to demonstrate in a practical way that the seemingly impossible is possible,” he notes in his book Factfulness.

It’s human tendency to be bored with stories of everyday incremental progress, and to focus on the negative — for which the state of the world in the 21st century provides much material. So much is in fact terrible and heartbreaking: the refugee crisis, melting glaciers, plastic in the ocean. From pandemic breakout to climate change, there are real dangers to be concerned about.

Why the bleak view?

But so much more seems to be wrong, and not getting better. This has made cynics of most of us. In Factfulness, Rosling suggests 10 instincts that prevent us from seeing real progress in the world. These include the tendency to negativity, fear, and blame. He also describes the ‘straight line’ instinct, by which he means the tendency to view trends as unchanging. But as he shows, not all changes in the world happen in this way.

But so much more seems to be wrong, and not getting better. This has made cynics of most of us. In Factfulness, Rosling suggests 10 instincts that prevent us from seeing real progress in the world. These include the tendency to negativity, fear, and blame. He also describes the ‘straight line’ instinct, by which he means the tendency to view trends as unchanging. But as he shows, not all changes in the world happen in this way.

The most dramatic chart in the book shows the average number of babies per woman from 1800 to today. It is not a straight line: more like a slide in a playground. Over the last 50 years this number has dropped from five children per woman to below 2.5. As child mortality reduced, as families came out of extreme poverty, as women and men got more years of education, as access to contraception increased, people were able to feed their children better and send them to school — and thus had fewer children.

When things get better, Rosling notes, such as the decrease in child mortality across the world, it is not just because of heroic individuals, but systems. Lots of people working together at the frontlines in a sustained way, every day, over the long term, to bring the incremental changes that, together, constitute progress.

The India connection

Rosling’s life has a special India connection: he studied public health at St. John’s Medical College, Bengaluru, and qualified as a doctor in 1976. He describes his first lesson there as a fourth-year medical student: “How could they know much more than me? Over the next few days I learned that they had a textbook three times as thick as mine, and they had read it three times as many times. I suddenly had to change my worldview: my assumption that I was superior because of where I came from, the idea that the West was the best and the rest would never catch up.”

Family stories are also a part of the book, contributing to its personal tone. As a child, he remembers his father taking him every Saturday, by bicycle, to hospital to visit his mother who had tuberculosis. “Daddy would explain that if we went in we could get sick too. I would wave to her and she would wave back…”

Family stories are also a part of the book, contributing to its personal tone. As a child, he remembers his father taking him every Saturday, by bicycle, to hospital to visit his mother who had tuberculosis. “Daddy would explain that if we went in we could get sick too. I would wave to her and she would wave back…”

But the story didn’t end sadly. “A treatment against tuberculosis was invented and my mother got well. She read books to me that she borrowed from the public library. For free. I became the first in my family to get more than six years of education, and I went to university for free. I got a doctor’s degree, for free. Of course nothing is free: the taxpayers paid.”

Life-changing tales

Another story describes how a washing machine changed their lives. “My parents had been saving money for years to be able to buy that machine. Grandma, who had been invited to the inauguration ceremony, was even more excited. She had been heating water with firewood and hand-washing laundry her whole life.”

Family, education, advances in health care, tax-funded social security, labour-saving devices, functioning democracies: these are all things to be grateful for. And a way of showing appreciation would be to read the data, because otherwise we would be missing the entire picture.

The book is the product of enormous research, but the tone is light rather than ponderous. It makes a complicated world appear simple, without foolish optimism, stereotypes or cliché.

The book is the product of enormous research, but the tone is light rather than ponderous. It makes a complicated world appear simple, without foolish optimism, stereotypes or cliché.

Factfulness is densely illustrated with charts and pictures, including the inside covers, but at the heart of the book is Rosling’s ability to listen, discuss and learn from other people everywhere.

Published after Rosling’s death, the book was written while he was under palliative care for pancreatic cancer. It is a book about his life and ideas, but it is also about how to pay attention to the world.

0 thoughts on “Factfulness: Ten Reasons We’re Wrong About The World – And Why Things Are Better Than You Think”