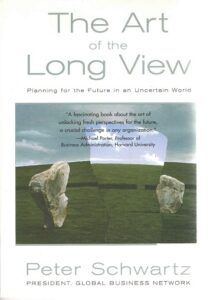

The Art Of The Long View: Planning For The Future In An Uncertain World

by Peter Schwartz

About The Author:

Peter Schwarz is one of the world’s leading futurists. He is president of the Global Business Network, an international think tank and consulting firm in Emeryville, California, that includes many of the world’s leading-edge thinkers about the future, as well as innovative scientists, artists, and business executives, His previous publications include Seven Tomorrows, a book of global scenarios jointly authored with Paul Hawken and Jay Ogilvy.

About The Book

What increasingly affects all of us, whether professional planners or individuals preparing for a better future, is not the tangibles of life – bottom-line numbers, for instance – but the intangibles: our hopes and fears, our beliefs and dreams. Only stories – scenarios – and our ability to visualize different kinds of futures adequately capture these intangibles.

In The Art of the Long View, now for the first time in paperback and with the addition of all-new User’s guide, Peter Schwarz outlines the “scenaric” approach, giving you the tools for developing a strategic vision within your business.

Schwartz describes the new techniques, originally developed within Royal/Dutch shell, based on many of his firsthand scenario exercises with the world’s leading institutions and companies, including the white House, EPA, BellSouth, PG&E, and the International Stock Exchange.

Praise for The Art of the Long View

“A fascinating book about the art of unlocking fresh perspectives for the future, a crucial challenge in any organization.”

Michael Porter, Professor of Business Administration, Harvard University

“Artful scenario spinning is a form of convergent thinking about divergent futures. It ensures that you are not always right about the future but – better – that are you are almost never wrong about the future. The technology is powerful, simple and enjoyable, and so is Schwartz’s book.”

Stewart Brand

Author’s Note

About ten miles north of Stonehenge, in the county of Wilshire, England, there exists another monument to prehistoric times – another message from the past coded in sandstone and chalk pillars. This site is called Avebury. It lies near a four-thousand-year-old path called the Ridgeway, which may be the oldest road in Europe. If you walk that path yourself, down the stone-lined avenue to the stone circle, and look east towards the morning sky, you will see a view like the cover of this book. A French artist named Paul Malcarnet painted the three stones, and made the middle stone, in the foreground, into a portal to an unexpected bright sky.

I have looked at this painting many times, starting with its first exhibition in 1986, by the Francis Kyle Gallery, and now in my home. I cannot see it without thinking of the stones as three separate views of possible futures. There, in the middle, is a future of hope, one which we might not have seen unless we looked for it. We do not expect to see it; indeed we do not understand it. But it changes our world.

Introduction to the Paperback Edition: The Strategic Conversation – Broadening the Long View

The book in your hands presents the art of “taking the long view” of decisions that need to be made today. As you (or your organization, or your enterprise) prepare to invest or pull back investment, to engage yourself or to disengage, to establish or close down a project, to move into new parts of the world or establish new relationships, how can you think best about the impact of your actions? How can you see, most clearly, the environment in which your actions will take place, and how those actions will fit with (or stand against) the prevailing forces, trends, attitudes and influences?

The book in your hands presents the art of “taking the long view” of decisions that need to be made today. As you (or your organization, or your enterprise) prepare to invest or pull back investment, to engage yourself or to disengage, to establish or close down a project, to move into new parts of the world or establish new relationships, how can you think best about the impact of your actions? How can you see, most clearly, the environment in which your actions will take place, and how those actions will fit with (or stand against) the prevailing forces, trends, attitudes and influences?

I wrote this book, initially, to show managers, business readers, and individuals how to begin using a method for investigating important decisions, a method that I and my close associates have found extremely useful for more than twenty years. And yet, this method is overlooked by most planning processes, usually because (although it involves analysis) it’s not “quantitative enough.” This method is the scenario – a vehicle, as my colleague Napier Collyns says, for an “imaginative leap into the future.”

In a scenario process, managers invent and then consider, in depth, several varied stories of equally plausible futures. The stories are carefully researched, full of relevant detail, oriented towards real-life decisions, and designed (one hopes) to bring forward surprises and unexpected leaps of understanding. Together, the scenarios comprise a tool for ordering one’s perceptions. The point is not to “pick one preferred future,” and hope for it to come to pass, (or, even work to create it – though there are some situations where acting to create a better future is a useful function of scenarios). Nor is the point to find the most probable future and adapt to it or “bet the company” on it. Rather, is to make strategic decisions that will be sound for all plausible futures. No matter what future takes place, you are much more likely to be ready for it – and influential in it – if you have thought seriously about scenarios.

This book will take you through the scenario process from beginning to end. We’ll begin by learning how to articulate and isolate key decisions, those most relevant to your company. We’ll then look at timing – Are your concerns likely to be illuminated by scenarios set five years into the future? Or ten years, and even more? The next step is in-depth research, including research in places you might not ordinarily think of looking (such as “fringe” publications, conversations with “remarkable people,” and challenging environments.) we will then look closely at driving forces, key factors that will determine (or “drive”) the outcome of the stories you are building. Some of these forces, you will decide, are predetermined you already know how they will play out in your chosen time frame. Other forces are critical uncertainties, pivotal elements that will act unpredictably, and thus might influence your future. You will learn that as you talk, in depth, about the significance of each of the driving forces, plots develop into stories, and scenarios take shape. The most essential step in the process comes at the end: Rehearsing the implications. Act out your options in each of the future worlds and refine your understanding of all of them.

The scenario process provides a context for thinking clearly about the impossibly complex array of factors that affect any decision. It gives managers a common language for talking about these factors, starting with a series of “what-if” stories, each with a different name. Then it encourages participants to think about each of them as if it had already come to pass. “What if our worst nightmare took place and our primary business became obsolete?” Or, “What if our most desired future came to pass? What unexpected challenges would it present to us?” Or, “What if a completely unexpected series of events changed the structure of our industry? Would we be overwhelmed, or would we see the opportunities?” In the early 1980s oil companies ought to have asked themselves, “What if the price of oil collapses?” While movie studios ought to have asked themselves, “What is the VCR creates new video-rental markets than killing off the movie theatre (as they feared)?”

Thinking through these stories, and talking in depth about their implications, brings each person’s unspoken assumptions about the future to the surface. Scenarios are thus the most powerful vehicles I know for challenging our “mental models” about the world, and lifting the “blinders” that limit our creativity and resourcefulness. Organizations that have instilled the scenario practice into their deliberations – including the royal Dutch/Shell Group, Pacific Gas and Electric, Motorola, and my own company, Global Business Network – have managed to anticipate difficult times and opportunities that have caught managers of other organizations unawares.

In the chapters that lie ahead, you will find detailed discussions of these uses of the scenario method. Now that five years have passed since the publication of The Art of the Long View, I realize that the scenario method also does much more. It can be used as a building block for designing strategic conversations – conversations that, in themselves, lead to continuous organizational learning about key decisions and priorities.

Thus, when Doubleday’s editors asked me to create a “Users Guide” for the paperback edition, I saw that invitation to expand “the art of the long view” to include the practice of strategic conversation. You’ll learn how to use the scenario method in the main text of the book, and you’ll find more information on the strategic conversation – and practical guidelines for starting a conversation – in the Afterword and User’s guide. Once you understand the value of the strategic conversation’s balance between formality and informality, your scenario work will take on another dimension. It will no longer be project specific, oriented to particular events. It will be part of an ongoing organizational learning process, robust and flexible enough to keep the organization from being blindsided by unexpected events, but intimately interwoven with the organization’s existing practices and relationships. Experience has shown that looking into the future is most useful when it is the beginning, not the end, of a significant conversation. The most successful managers, I believe, are those who will see their fundamental work not as making decisions, but as making mutual understanding.

Thus, when Doubleday’s editors asked me to create a “Users Guide” for the paperback edition, I saw that invitation to expand “the art of the long view” to include the practice of strategic conversation. You’ll learn how to use the scenario method in the main text of the book, and you’ll find more information on the strategic conversation – and practical guidelines for starting a conversation – in the Afterword and User’s guide. Once you understand the value of the strategic conversation’s balance between formality and informality, your scenario work will take on another dimension. It will no longer be project specific, oriented to particular events. It will be part of an ongoing organizational learning process, robust and flexible enough to keep the organization from being blindsided by unexpected events, but intimately interwoven with the organization’s existing practices and relationships. Experience has shown that looking into the future is most useful when it is the beginning, not the end, of a significant conversation. The most successful managers, I believe, are those who will see their fundamental work not as making decisions, but as making mutual understanding.

Afterword: The Value of a Strategic Conversation

Corporate managers are often caught by surprise. Corporate policies are often undone by unexpected changes in the environment – by sudden rises or drops in the price of raw material, by a competitors technological breakthrough, or perhaps by a change in the regulations that set the boundaries of the companies “playing field.” Being blindsided, managers often then make decisions that, in the end, exacerbate the original problem. “If we had only known what’s going on,” the responsible managers eventually say, “we could have avoided this crisis.”

Corporate managers are often caught by surprise. Corporate policies are often undone by unexpected changes in the environment – by sudden rises or drops in the price of raw material, by a competitors technological breakthrough, or perhaps by a change in the regulations that set the boundaries of the companies “playing field.” Being blindsided, managers often then make decisions that, in the end, exacerbate the original problem. “If we had only known what’s going on,” the responsible managers eventually say, “we could have avoided this crisis.”

But there is often a profoundly depressing moment, late in the game, when the responsible managers realize that they did know what was going on. Or, at least, they had access to the necessary information. Somewhere within the corporation, there was a perceptive executive (often more than one individual) who understood the nature of the changes facing the company. But that understanding never broke through to the awareness of the people with the power to act.

Perhaps the understanding represented a view that dissented from the conventional wisdom of the firm, and the corporate culture subtly punished people for trying to express such views. Perhaps the prophets within the firm were disregarded because they were new: “They haven’t been around long enough to see things as we do.” Or perhaps they came from a low-status division or function: “the R&D people always talk about lost opportunities, but they don’t know what’s going on.”

Or, most tragically of all, perhaps strategy – the setting of priorities for the company’s long-term development – was considered the province of specialists: senior managers and selected staff people who rarely communicate the strategic concerns and questions to people throughout the organization. Therefore, at various levels, different people understood different aspects of the company’s environment, but never had a chance to talk about them, and thus to put the pieces of the puzzle together. Because the story was never fully formed, it never percolated to the specialists and decision-makers who were responsible for the “strategy.” Is it any wonder that the resuting strategy was narrow, and shockingly uninformed?

Examples of organizations that have missed opportunities in this manner are legion. IBM’s failure to anticipate and move with the potential of distributed computer processing (brought about by the personal computer) is a classic case of this. (It was particularly poignant because IBM did such a good job of anticipating and riding the first personal computer wave.) Another example is Apple Computer’s refusal to license its operating system to other manufacturers – while VHS and Betamax videotape formats were staring at them in the face. (VHS, as a widely licensed standard, trounced Sony’s Betamax format.) The global auto industry regularly endures episodes in which group-think leads to a dramatic shift among winners and losers. Recently, for example, while nearly evry auto manufacturer was focusing on providing high-mileage, low-emission vehicles, the customer base began abruptly buying sports utility vehicles and light trucks. Honda, which had done remarkably well in an earlier era, was suddenly caught off guard with no suitable vehicles for that market.

There are also, however, a legion of companies that have thrived on change. Motorola, Hewlett-Packard, and Rubbermaid, for example, are known for their resilience in change after change, as one business environment follows another. Yet the cultures of such companies are strangely calm. Managers there are continually involved in a collective inquiry into the deep structure of their business and how it is changing. They are hunting for new information, and they continually bring questions of possibility – “What if an opportunity emerged?” “What if an unexpected crisis took place?” – before the attention of people throughout the company.

There are also, however, a legion of companies that have thrived on change. Motorola, Hewlett-Packard, and Rubbermaid, for example, are known for their resilience in change after change, as one business environment follows another. Yet the cultures of such companies are strangely calm. Managers there are continually involved in a collective inquiry into the deep structure of their business and how it is changing. They are hunting for new information, and they continually bring questions of possibility – “What if an opportunity emerged?” “What if an unexpected crisis took place?” – before the attention of people throughout the company.

In short, people at resilient companies continually hold strategic conversations about the future.

Informal, Explicit, Relevant…and Fun

A strategic conversation is a carefully thought-out but loosely facilitated series of in-depth conversations for the key decision-makers throughout an organization. Strategic conversations don’t exist in addition to existing planning efforts; they are effective ways of framing the planning efforts that already take place, to further illuminate the decisions that are already being made.

A strategic conversation is a carefully thought-out but loosely facilitated series of in-depth conversations for the key decision-makers throughout an organization. Strategic conversations don’t exist in addition to existing planning efforts; they are effective ways of framing the planning efforts that already take place, to further illuminate the decisions that are already being made.

Perhaps most significant of all, a strategic conversation is informal – or, more precisely, it combines formal and informal elements. To understand the importance of this point, consider the formal business planning process that most people think of when they hear about an organization’s “strategy.” This process often involves carefully scripted presentations, scheduled according to a structured cycle, in which senior managers pronounce judgements on strategic plans. But by the time proposals get to the final stage of presentation, they have almost always gone through an elaborate, but unacknowledged, informal process of development and testing to assure that they will pass this hurdle. Once proposals reach that stage, there’s no opportunity for engagement.

Meanwhile, informal conversations take place everywhere – in the “invisible” strategy sessions of the elevator ride, the lunch room, or the car pool. In these “non-threatening” locales, ideas are developed and tested and these ideas ultimately become part of the formal proposals or strategic plan.

Unfortunately, since these informal conversations are almost entirely organized on a as hoc basis, they tend to provide ad hoc answers that reinforce the conventional wisdom. People make no concerted effort to bring themselves in contact, regularly and informally, with others who look at things differently, or who can offer a perspective and knowledge that they lack.

However, when an informal set of conversations is established in conjunction with a formal planning process, learning is encouraged. People know they are free to raise and debate questions without being held to account for the positions they take. Particularly when scenarios are part of the conversation, they can “try on” different futures and attitudes to see how they feel about them. Executives begin to look at their own companies, see the fundamental conditions of their success, and ask, “What if these were to change?” How will they be stressed to evolve next, they wonder, and could they anticipate that evolution before they feel the stress? The process of considering scenarios together allows these corporate leaders to question – and change – their mental models. As a result, the decision-makers have more confidence. They can move ahead, knowing that they have already been forced to talk at length, and muse together, about both the upside and the downside of their strategy. They are much less likely to get trapped by unexpected events.

This broadening is important because change in organizations is inevitably the prerogative of groups, and not individuals. Much writing about business creates the CEO as a “general,” who commands his (or, in all-too-rare cases, her) loyal troops. Those troops, in turn, are supposed to transform themselves in whatever direction the CEO points. In real life, CEOs of large organizations are well aware that groups of people don’t work that way. Getting a group to develop the capacity to change requires a high degree of shared worldview, and a mutual commitment to change. The magnitude of the commitment is critical; without it, no one can hope to divert, or even the momentum of, a large, complex system like a big company.

Moreover, the process is a great deal more fun for all involved than the standard business planning process. I mean this in the best sense of the word “fun” – the conversations are highly enjoyable experiences that engage the creativity of everyone in the room. As former Shell planning coordinator (and learning theorist) Arie de Geus has pointed out, fun – particularly in an organizational context – is a necessary prerequisite for learning, particularly for the type of strategic learning that is the source of an organization’s competitive advantage.

Moreover, the process is a great deal more fun for all involved than the standard business planning process. I mean this in the best sense of the word “fun” – the conversations are highly enjoyable experiences that engage the creativity of everyone in the room. As former Shell planning coordinator (and learning theorist) Arie de Geus has pointed out, fun – particularly in an organizational context – is a necessary prerequisite for learning, particularly for the type of strategic learning that is the source of an organization’s competitive advantage.

The Global Strategic Environment

Why, then, don’t most organizations get involved in strategic conversations? There are two reasons. First, they’re unfamiliar. Managers are not accustomed to holding informal conversations that explicitly feed into formal processes, even if conversations are taking place all the time.

Why, then, don’t most organizations get involved in strategic conversations? There are two reasons. First, they’re unfamiliar. Managers are not accustomed to holding informal conversations that explicitly feed into formal processes, even if conversations are taking place all the time.

Second, managers don’t think change is needed. Even in the 1990s, managers tend to consider only a narrow range of strategic options and ramifications. “Here are the costs of the new capitalproject,” someone might say, “and the return on investment” – and based on those two statements, the decision will be made to proceed with or abandon the project. There is little consideration given to how successful the project might be in a wide range of changing circumstances.

Perhaps that approach worked well when decisions were relatively small or events were relatively predictable. But in the foreseeable future, corporate managers will be confronted by situations that require large, difficult decisions. Once upon a time, a Pacific Gas & Electric manager might have to decide: “Should the next power plant be based on oil or gas production?” Today, the PG&E manager would be part of a team deciding: “Are we going to get out of the electric-generating business entirely and just become distributors of power? Should we sell all our existing plants in America? Should we build plants in Indonesia instead?

The ordinary planning process does not prepare people well for decisions like these. And such decisions are replicated in industry after industry. Book publishers must now consider whether they should remake their production processes, and how they should cope with the increasing (but unpredictable) evolution of the online environment. Chemical and mining companies must decide if their futures exist as commodity producers, as specialty chemical and drug producers, or as both, and they must seek the opportunities that come from the dematerialization (the increasing efficiency with shrinking material) of the industrial world.

Or consider the women’s clothing industry. This is a particularly good example because it’s managers are acclimated to change – or think they are. They know how to respond to abrupt demand for new colours or shifting hemlines. But now, in their business, the nature of change is changing. New methods of manufacturing make it possible to manufacture clothing almost anywhere, o a small scale with very high quality. New shopping malls have provided an oversupply of lookalike stores. And women, whose leisure time has decreased sharply in recent decades, spend less time (and money) shopping for new clothes. (For the last several years, women’s apparel sales have fallen about 3 percent per year.) Certainly, some observers and fashion writers pointed out these possible changes as early as 1987, while they were still nascent, but the industry largely failed to prepare, in part because industry leaders assumed that the “new simplicity” in women’s clothing was just another fad that would last a few seasons and fade.

But it didn’t fade. For it, and the other fashion industry crises, are the kind of discontinuities that require strategic thinking and conversation. They are not like hemline and colour shifts. They cannot be dealt with in the traditional business-as-usual way.

But it didn’t fade. For it, and the other fashion industry crises, are the kind of discontinuities that require strategic thinking and conversation. They are not like hemline and colour shifts. They cannot be dealt with in the traditional business-as-usual way.

Instability is the inevitable reality for every business in the near future. It is being driven in part by increasing knowledge, in the form of science and technology; by the ability to change more and more of the human condition by design; and by increasing use of global scale media (such as Cable News Network) by people around the world. CEOs and senior executives must ask themselves: do the large scale changes that we see (in our organizations and outside them) represent a one-time set of phenomena? Will the turbulent rapids of change clear out into a smooth, rapidly flowing stream of progressive stability, as the futurist Herman Kahn suggested? Or, as management writer Peter Vaill remarks, are we heading into an environment of “permanent white water?” And if so, can we build organizational forms that help us navigate through continual change?

0 thoughts on “The Art Of The Long View: Planning For The Future In An Uncertain World”