Yasmeen Lari: Architecture for the Future

RIBA Gold Medal Winner 2023

One of the world’s highest accolades for architecture, the Royal Gold Medal is personally approved by the monarch and awarded to a person or group of people who have had a significant influence on the advancement of architecture. Presented since 1848, past Royal Gold Medallists include Balkrishna Doshi (2022), Sir David Adjaye OBE (2021), Dame Zaha Hadid (2016), Frank Gehry (2000), Lord Norman Foster (1983), Frank Lloyd Wright (1941) and Sir George Gilbert Scott (1859).

The Royal Gold Medal will be officially presented to Yasmeen Lari in June 2023.

With a long and illustrious career, Lari has been a revolutionary force in Pakistan. She has had immeasurable influence of the trajectory of the architecture and humanitarian work in the country. Since officially retiring in 2000, she transferred her attention to creating accessible, environmentally friendly construction techniques to help people below the poverty line and communities displaced by natural disasters and the impact of climate change. In 1980 she co-founded the Heritage Foundation of Pakistan with her husband, Suhail Zaheer Lari, pioneering the design of self-build sustainable shelters and housing, creating 50,000 dwellings. Lari is also known for the design of the Chulah Cookstove, of which there are now over 80,000. An eco-alternative to a traditional stove, it significantly reduces emissions, tackling unfavourable environmental and health issues associated with cooking on an open fire.

Born in 1941 in Pakistan, Lari moved to London with her family aged 15. After finishing school, she studied art for two years before being accepted into the School of Architecture, Oxford Brookes University, then Oxford Polytechnic. After graduating in 1964, Lari returned to Pakistan at age 23 with her husband, Suhail Zaheer Lari, to establish her own architecture firm Lari Associates, going on to work for major government, business, and financial institutions. Since her ‘retirement’ in 2000, Lari has focussed solely on her humanitarian work, which has levered international recognition.

On hearing the news, Professor Yasmeen Lari said:

“I was so surprised to hear this news and of course totally delighted! I never imagined that as I focus on my country’s most marginalised people — venturing down uncharted vagabond pathways – I could still be considered for the highest of honours in the architectural profession.

RIBA has heralded a new direction for the profession, encouraging all architects to focus not only on the privileged but also humanity at large that suffers from disparities, conflicts and climate change. There are innumerable opportunities to implement principles of circular economy, de-growth, transition design, eco-urbanism, and what we call Barefoot Social Architecture (BASA) to achieve climate resilience, sustainability and eco justice in the world.”

RIBA President, Simon Allford said:

“It was an honour to chair the committee that selected Yasmeen Lari. An inspirational figure, she moved from a large practice centred on the needs of international clients to focussing solely on humanitarian causes. Lari’s mission during her ‘second’ career has empowered the people of Pakistan through architecture, engaging users in design and production. She has shown us how architecture changes lives for the better.

Lari’s work in championing zero carbon and zero waste construction is exemplary. She has reacted imaginatively and creatively making affordable projects that address the real and often urgent need for accommodation, and basic services, but with generosity and an eye for the potential of everyday materials and crafts to make architecture at all scales. Her way of working also sets out to address the physical and psychological damage caused by major natural disasters – disaster that sadly inevitably will be ever more prevalent in our densely populated and climate challenged planet.”

The 2023 Royal Gold Medal selection committee was chaired

by architect and RIBA President Simon Allford, and comprised: Ivan Harbour, architect and senior partner at RSHP; Cornelia Parker CBE RA; Neal Shasore, Chief Executive and Head of School at the London School of Architecture, and Cindy Walters, architect and partner at Walters & Cohen.

Official citation on Yasmeen Lari by the 2023 RIBA Honours Committee:

Having studied in the UK at Oxford Polytechnic (now Oxford Brookes), Yasmeen Lari took the decision to return to Pakistan where she became the country’s first female architect. She then overcame considerable challenges to establish her own commercially successful practice working for major government, business, and financial institutions.

Whilst recognising the importance of her role in practice, as a symbol of change in Pakistan, it is the work she has undertaken since her retirement in 2000 that the Royal Gold Medal celebrates.

In the last twenty-three years Lari and The Heritage Foundation of Pakistan, which she founded with her husband, has reacted imaginatively and creatively to the physical and psychological damage that a number of major natural disasters; earthquakes, floods and conflicts have inflicted on the people of Pakistan. Her work is distinguished by the fact that it has focused on developing robust, intelligent yet simple, architectural designs that allow those who are in distress to build for their own needs using the available debris of disaster. This is a very different, but also very relevant, model of re-use and reinvention that engages and empowers.

Continuing to test the potential of this architectural activity further, Lari has developed and shared a design and construct self-build model for shelters, using readily available bamboo to create economical and beautiful braced frames for inhabitation. This is a model of structure and enclosure that fulfils the need for long life, loose fit, and in her case, zero carbon architecture. There is an inherent generosity in Lari’s architectural activity that responds to need, helps communities develop artisanal skills and always utilises available resource. Lari’s design for 60,000 Chulah Cookstoves structures are a self-build version of the traditional Pakistani stove that enhances food preparation, hygiene and quality while creating a place for community. Always working to empower the most challenged communities at the most difficult times, Lari has most recently developed designs for a system that allows the construction of 100 emergency shelters in four days.

Now working on the repair and regeneration of a key district of historic Lahore, Lari’s work builds on her commitment to recycling materials and buildings. This suggests another model of conservation and builds on the promise of her important early work in Lahore: the Anguri Bag housing scheme.

Lari’s vital contribution identifies different ways of working which suggest how the international architecture profession can play an ever more useful role in helping communities to help themselves, while also responding to climate change.

It is Lari’s focus on architecture as a complete and vital social, cultural, economic and aesthetic model, as well as her mantra of ‘low cost, zero carbon, zero waste’ that makes her hugely relevant to all who practice today.

Essentials for Life

Angelika Fitz

Millions of people live without a safe roof over their heads, without access to clean water, or without sanitary infrastructure. Deprived of basic human rights, they are particularly vulnerable in the event of a disaster. Yasmeen Lari sees the discipline of architecture as the duty to develop viable and sustainable solutions for essential infrastructure. Not just a small minority but the majority of the world’s population should benefit from architecture in the future. As always, her architectural thinking and actions go beyond the individual building. She designs and tests asystemic approach that aims to tread lightly on the planet.

It is about finding out which method is the most cost-effective, safest, and most economical, and then implementing it en masse, says Lari. In her integrative approach, this applies not only to accommodation, but also to the supply of clean water, safe toilets, healthy cooking facilities, and community spaces. For these basis needs, she develops zero-carbon infrastructures that take care of the planet as well as work toward the survival of people, and especially towards improving the lives of women, who are responsible for many life-sustaining activities. A Pakistan Chulah (smokeless stove) uses half the fuel, can be built by families themselves, and provides a pleasant place to work and gather, which remains functional during floods, as do the water pumps raised on platforms. The safe toilets spare the women the dangerous nocturnal walk in the fields.

There are almost no building costs, since local materials such as mud, lime, and bamboo are used for construction. People can do it themselves, guided by those members of the community who have received training from the Heritage Foundation and who, by passing on this knowledge, generate an income that contributes to their livelihoods. A handmade seriality ensures efficiency and clearly regulated reporting systems for security. The poorest meet the needs of the poorest, that is how Lari describes this economy and adds that not only essential infrastructure is build, but also a life in dignity.

Safe houses and sanitary infrastructure are a human right and particularly important for women.

Shelter

According to Yasmeen Lari, the immense need for affordable and safe accommodation in countries like Pakistan cannot be met with conventional social housing programs. Concrete and cement homes are too expensive for millions of people, and they harm the environment in a region particularly hard hit by the catastrophic effects of climate change. Moreover, they are often not safe due to poor material quality and construction.

Working in earthquake and flood areas, Lari has continuously developed self-construction methods for extremely inexpensive zero-carbon houses. Tens of thousands of such structures were built in a few years. The house forms are derived from vernacular traditions in different regions of Pakistan, the materials also avry regionally from stone to mud and straw. Transverse bracing made of bamboo and lime mortar guarantee stability that withstands even strong earthquakes. The possibility of prefabrication takes the time factor into account. With the Lari OctaGreen (LOG), accommodations can be erected in a very short time with serially prefabricated bamboo modules.

The overhanging roof construction made of bamboo can be designed as a flat roof that can be walked on and greened with plants or as a pent or gable roof.

The areas surrounding major rivers such as the Indus, which crosses Pakistan from north to south, are scenes of catastrophic flooding, but also a resource for clay processing. Unfired clay can be used in Lari’s zero-carbon architecture in the form of sun-dried bricks and adobe construction. Lime mortar and bamboo provide stability. Where trees are scarce, the fast growing bamboo is more environmentally friendly than wood. Fossil fuel is only needed for the preparation of lime, but the environmental balance is significantly better than with cement as Lari explains. All materials are available locally, mostly free of charge, and can be processed by the residents according to Lari’s detailed instructions.

So, the most affordable, the most inexpensive, the safest thing that you can do, you need to do for everybody. – Yasmeen Lari, 2022

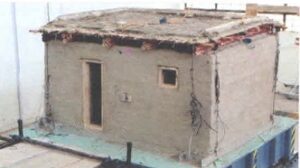

Shaking Table

At the NED University of Engineering & Technology in Karachi, under the supervision of Vice Rector Sarosh Hashmat Lodi, the earthquake resistance of the house construction made of mud, lime and bamboo was tried and tested on the “shaking table” – simulating tremors many times greater than the 1995 earthquake in Kobe, Japan, where a magnitude greater than 7 was first measured on the JMA Seismic Intensity Scale.

When you work for the poor, you are trying to save their lives, but you are also trying to save the planet. – Yasmeen Lari, 2019

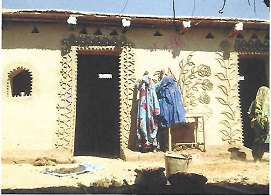

With Lari’s zero-carbon techniques, existing buildings in the village setting can also be replaced, repaired, and made disaster-resilient. Elevated platforms create safe communal spaces, like here in Sindh Province.

In contrast to concrete, mud is a material that women without an income of their own can produce and process. Mud is also used by them to decorate their houses, as part of a personal appropriation. In the picture is the house of Rani and Dharmi Bibi.

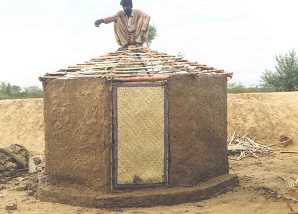

Lari OctaGreen (LOG)

The octagon-shaped LOG buildings can be erected in a few hours form prefabricated bamboo modules and offer immediate protection from rain, wind, and snow. By filling the bamboo panels with clay, the ‘first-aid’ shelters become permanent houses that can be connected to form larger structure. They are plastered with a mixture of mud and lime. Derived from traditional forms in Sindh Province, the cone-shaped roof becomes disaster-resistant with structural improvements. The roof construction is sealed with mats of straw, mud-lime plaster, and then with a pozzolana-like mixture of lime and brick dust.

In the Heritage Foundation training program, craftsmen and unskilled workers learn how to manufacture modules for the Lari OctaGreens (LOG). They are prefabricated jointly at central locations in the villages, so the quality and safety of the construction are constantly checked before they are erected by the villagers. The cross braces are derived from traditional dhijjis in the northern provinces of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Kashmir – this construction method proved to be the most stable during the 2005 earthquake. The panels are covered with mats woven from palm straw.

During the devastating floods of summer 2022, bamboo modules for Lari OctaGreens (LOG) were being prefabricated at the Zero Carbon Cultural Centre in Makli to provide emergency relief to homeless villagers.

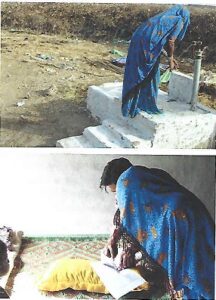

Drinking Water

Access to clean water is another basis of life. Groundwater is mostly available in Pakistan, says Yasmeen Lari, but rarely to villagers in close proximity. In the Heritage Foundation program, five families each share the cost of a well. To ensure that they remain functional during the increasingly fierce monsoon rains, the wells are built as elevated platforms. Again, the load is especially taken off women, who are responsible for the care of people and animals and often have to transport the water over long distances.

A well is used jointly by several families. The elevated platform protects against contamination, especially during floods.

The essential infrastructures built locally under the guidance of the Heritage Foundation are part of a predefined reporting system. The quality control lies in the hand of the individual households, who receive a checklist.

Cooking

There is no life without food. A good infrastructure for the daily preparation of meals is essential. Poorer families in Pakistan – and in many other countries – rely on open fires for cooking. This repeatedly leads to burns, especially suffered by children, and sometimes to threatening fires. The heavy smoke that develops when cooking damages the respiratory organs and the eyes, which restricts the living situation of the women affected. Last but not least, the high consumption of fosil fuels is bad for the environment.

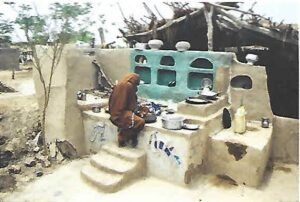

Yasmeen Lari developed the smokeless Pakistan Chulah (Pakistani stove), which consumes only half the fuel. In contrast to international aid programs, no industrially manufactured metal stoves are used. The Pakistan Chulahs can be built by the families themselves from the local materials of mud and lime under the guidance of the “Chulah Adhis” (Stove Sisters), who received training from the Heritage Foundation.

In 2011, Lari started the first experiments in Moak Sharif. Systematic training was carried out in 2014 with the support of the ILO (International Labor Organization) and in 2015 by the IOM (International Organization for Migration). The process is now self-sustaining: the Chulah Adhis and their husbands show the families how they can build the innovative stoves themselves and get apid two hundred Pakistani rupees (approximately 2 US dollars) for doing so. Seventy thousand Pakistan Chulahs have been erected in this way so far. In 2018, the Pakistan Chulah received the UN Habitat Award.

For the Pakistan Chulah, a platform is made of sun-dried mudbricks, plastered with a mud-lime mixture is erected. Far more hygienic than cooking on the ground, the elevated platform is also protected from flooding. The position of the women responsible for cooking rises symbolically, too. Additional structures for storing cooking utensils are individually designed by the women.

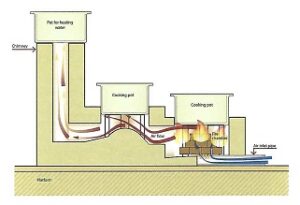

The Pakistan Chulah enables two cooking zones to be operated with one fire chamber. Waste materials such as cow manure or sawdust and only a little wood are used for firing. The chimney reduces any direct exposure to pollution and can be used as an additional heating plate.

The platforms of the Pakistan Chulahs are not only secure working spaces, but also pleasant and communicative places for women and children.

The Story of a Chulah Adhi (Stove Sister)

Together with her husband Kanji, Champa has guided the self construction of thousands of Pakistan Chulahs and thereby improved the living conditions of the families. They live in Mirpur Khas in Sindh Province and, as members of a local minority, were able to overcome their own precarious situation with the income they generated. In the meantime, they have also trained other teams.

Safe Toilets

Visibly moved, Yasmeen Lari describes why toilets are one of the most important infrastructures for a life in dignity, especially for women: “When I asked women, ‘What do you do for toilets?’ they said: Well, in the morning, before early morning prayer, the Fajr prayer, and after Maghrib, which is the sunset prayer, we go behind the bushes, that is where the toilet is.”

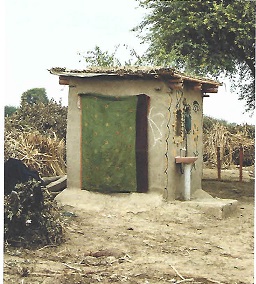

The toilets developed by Yasmeen Lari once again follow the principles of utilizing extremely low-cost, local, and mostly zero-carbon materials and self-construction so that everyone has access to sanitary facilities. As with Lari’s zero-carbon houses, the walls are built from sun-dried mudbricks or from prefabricated bamboo panels plastered with mud and lime. The floor is preferably hygienically sealed with a pozzolana made of lime and brick dust. A closable pit contains the bucket for the excrement used to make fertilizer. Next to it is space for a shower.

Hygienic sanitary rooms that ensure privacy enable women in particular to live in dignity and security.

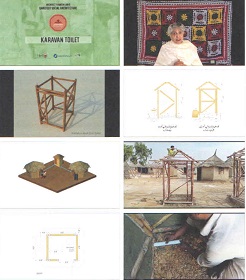

Karavan Toilet

On her digital Zero Carbon Channel Yasmeen Lari shares instructions for building toilets. “Karavan Toilet” is the name she gives to the prefabricated bamboo version.

Video stills: Yasmeen Lari’s Zero Carbon Channel on YouTube, 2021

There is not a single woman I have spoken with who is not willing to do anything to improve her life. – Yasmeen Lari. 2022

Community

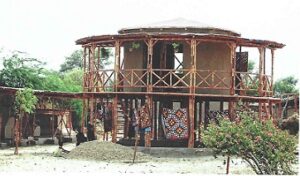

Yasmeen Lari’s work is exemplary of how architecture can create vital infrastructure for millions of people without exploiting the planet and polluting it with emissions. Life and survival not only include physical integrity but also the basic human need for social exchange and cooperation. In addition to schools, Lari sees a great need for community spaces for women who are ties to a small area by htier domestic work and only have access to social gatherings on rare occasions, such as weddings or

funerals. Lari’s Green Women’s Centres provide shelter and opportunities for collective action. Lari says she has not met a single woman who was not willing to do whatever it takes to improve her life.

The Green Women’s Centre in Darya Khan Sheikh, Sindh Province, is a meeting place and shared learning space for women. In the event of flooding, household goods and small animals can be brought to safety on the upper floor.

The construction site of the Green Women’s Centre in Darya Khan Sheikh made of bamboo.

Women gather at the Green women’s Centre in Darya Khan Sheikh in 2011 for a meeting with Yasmeen Lari. For Lari, women are important partners on the way to a zero-carbon future.

0 thoughts on “Yasmeen Lari: Architecture for the Future”