Alternative Building Forms & Massing: Pro’s & Con’s – Horizontal or Vertical

In the First World countries of the West, the trend in the recent past has been to steadily move away from hospitals organized primarily around vertical circulation systems. This trend has been most marked in the UK, where the Nightingale-inspired horizontal pavilion hospital never died out, as it did in many other countries.

Wexham Park Hospital at Slough, designed by Powell and Moya (with John Weeks) in the late 1950’s, was a seminal building. It’s village form led in one direction to Week’s Northwick Park Hospital (already discussed in a previous design tip), and, in the other, by the development of it’s wide span structural design, to the Greenwich Hospital (also discussed previously).

This eventually led to the development of the Nucleus hospitals by the NHS in the UK, which are mainly of two or three-storey construction, comprising standard departments on either side of a hospital street, a zone combining main circulation and services distribution.

Developments in some other countries have been influenced by British ideas – for example, that of Greenwich on the USA Veterans Administration system, and particularly its prototypical hospital at Loma Linda in California. The same logic that drove the British sequence of developments has been evident in other countries.

The inherent problems of vertical organization, and particularly of a tower block of wards, is that of a limited envelope with no means of lateral expansion. The considerable portion of each floor taken up by lifts, stairs and service shafts, is not only inherently wasteful and expensive, it also makes the plan form more rigid, and inhibits subsequent alteration. Growth of a vertically organized hospital tends to take the form of clusters of smaller blocks at its base, with increasingly difficult service and circulation routes.

Tall buildings are more likely to need expensive climate control, to consume more energy, and have greater problems of evacuation in cases of fire than have lower ones, in which horizontal evacuation is through successive protected zones further away from the source of the fire.

The advantage frequently claimed for tall hospitals is that they occupy less land. This is only valid for inner urban hospitals, such as the (moderately) tall Chelsea and Westminster Hospital, London, where the floor area is similar at all levels. The commonest type of tall hospital, especially in the USA, is the “tower on podium” form, popularized by Gordon Friesen with his mineworkers hospitals, and based on a production engineering principle of supplies fed the wards from a basement service center. The podium of these hospitals usually spreads to occupy a site similar to those of compact low-rise hospitals. The flexibility limitations of such hospitals become more evident as the proportion of the total built volume comprising wards is tending to diminish.

The tower and podium form is common in other building types, notably – and for similar reasons – hotels. Lever House in New York had a great influence, and not only on other office buildings. Although the earliest Friesen hospitals pre-date Lever House, the prevalence of hospitals of this form in the USA from the 1950’s onwards may be partly attributable to a much admired “classic” of modern architecture.

It is arguable, however, that hospitals, with their functional complexity and unknown ultimate form, are more suitable for the alternate organic stream of modern architecture, typified by Wright, Aalto and Scharoun, than for the purist geometry typical of Mies and his followers. It may be significant that Aalto’s Paimio sanatorium is the only hospital among the undisputed masterpieces of modern architecture.

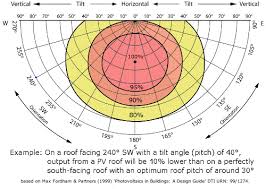

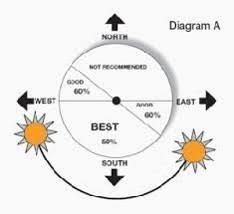

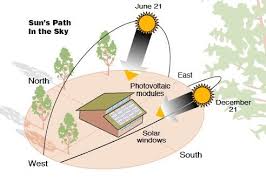

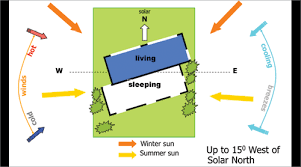

Many times, the building form and massing could largely be determined by the climate of the location of the proposed hospital, that is, the designer’s response to these characteristics of the site. The amount of care taken in placing and orienting a building on the site with respect to open spaces and the sun is perhaps the single most important decision you will make regarding the building with respect to its response to the climate.

With an idea for the location of the building on the site, it is necessary to determine the rough shape of the building before laying out interior spaces. Buildings shaped without regard for the sun’s impact require large amounts of energy to heat and cool. Large amounts of energy are used to heat and cool buildings all over the world. In spite of worldwide dwindling energy resources, many buildings today are still shaped without regard for the sun’s impact on, and potential contribution to, space heating and cooling.

This is an approach to architecture made necessary and timely in an era of rapacious energy consumption. We need more than ever before to follow a way of building that is strongly related to site, climate, local building materials and the sun. It implies a special relationship to natural processes that offers the potential for an inexhaustible supply of vital energy. Much vernacular architecture has always reflected a strong relationship to daily and seasonal climatic and solar variations.

Nowadays the architect’s approach to problem solving has been characterized by an emphasis on technology to the exclusion of other values. In the built environment this concern manifests itself in the materials we build with, such as plastics and synthetics. Especially in healthcare facility design, there is great dependence on the mechanical control of the indoor environment rather than the exploitation of climatic and other natural processes to satisfy our comfort requirements. In a sense, we have become prisoners of complicated mechanical systems, since windows must be inoperable and sealed in order for these systems to work. A minor power or equipment failure can make these buildings uninhabitable. Little attention is paid to the unique character and variation of local climate and building materials. One can now see essentially the same type of building coast to coast.

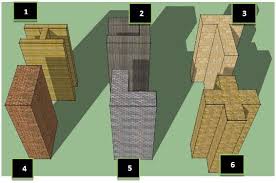

Shown below are various configurations of hospital built form:

Orientation of the building with respect to the movement of the sun

Architectural Design Process | Form, Orientation and Sunlight

Developing the Architectural Concept – Architecture Short Course (Part 2)

0 thoughts on “Alternative Building Forms”