Conflicts of Interest: My Journey Through India’s Green Movement

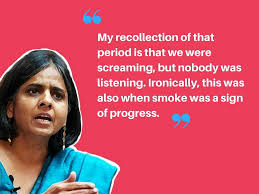

By Sunita Narain

About The Author:

Sunita Narain is an environmentalist and political activist who uses knowledge to push for changes in policy and practice. She has been with the Centre for Science and Environment since 1982 and is currently it’s Director General. She is also the editor of the fortnightly magazine Down To Earth. For her tireless struggle for a cleaner environment in a fast-growing economy, Narain was included in Time magazine‘s list of 100 most influential people, in April 2016, where her profile was written by Amitav Ghosh.

Hers was a compelling voice in Before the Flood, a feature-length documentary produced and presently by Leonardo DiCaprio and released in October 2016.

Contents:

Introduction: Contested Realities

1. Air Pollution: Breathless

2. Endosulfan’s Curse

3. Cola Wars

4. Climate’s Change

5. Tigers and/or People

6. Water and Waste Wars

7. A Blueprint for the Future

Introduction: Contested Realities

This book is a journey, one I would never have undertaken. Never, Because in our work, looking back is a privilege. Every day there is a new challenge that forces us to learn more and to push forward more. In fact, in the kind of work we do, which is mostly frustrating and often deeply disturbing, the only way to stay ahead is to keep a tunnel view – focus on where we need to go – with a single-minded obsession. Or desperation. That is what keeps my adrenaline going. And frankly it’s the only way not to let the sense of hopelessness – given the immensity and often the sheer futility of the task – make you go under.

This book is a journey, one I would never have undertaken. Never, Because in our work, looking back is a privilege. Every day there is a new challenge that forces us to learn more and to push forward more. In fact, in the kind of work we do, which is mostly frustrating and often deeply disturbing, the only way to stay ahead is to keep a tunnel view – focus on where we need to go – with a single-minded obsession. Or desperation. That is what keeps my adrenaline going. And frankly it’s the only way not to let the sense of hopelessness – given the immensity and often the sheer futility of the task – make you go under.

But I also have to confess that writing Conflicts of Interest has been gratifying and fulfilling. It allowed me to put our work of many years in perspective; it allowed me the chance to see the whole picture. Not the grisly snapshots of the current battle, but what worked and what did not.

There are many lessons – or let me say interconnected strands – in our tale I find.

First, there is the issue of the issue itself. Often, we are so lost in the problem that we lose our ability to propose what should be done. This push for answers is what I believe has been our most important contribution. But it is even more difficult to stay the course to push for implementation. There are a billion-plus Indians; we are born with ideas and, of course, we are well-oiled critics. So, what is really difficult is not to fight that contested reality, but in the fight one should not lose focus.

Then there is the problem of the problem itself. In India, there are so many things that need to be done and all are needed to be done yesterday. How do you prioritize? How do you choose not to respond to a call of distress? How do you decide that you will not work to get justice for a group of people who are. say, being devastated by a polluting factory or a mine or deforestation? How do you not get involved?

This, when you know that each problem is a world in itself. Our work of over thirty years shows that each issue is contested, and it takes time to get results. Take air pollution. We started work in the mid-1990’s, got some victories by early 2000, but are now back in the fray. The cycle requires you to persist and persist.

This, when you know that each problem is a world in itself. Our work of over thirty years shows that each issue is contested, and it takes time to get results. Take air pollution. We started work in the mid-1990’s, got some victories by early 2000, but are now back in the fray. The cycle requires you to persist and persist.

And all this is when we have an institution, the Centre for Science and Environment (CSE) to back us. The fact that, in 1980, Anil Agarwal returned from his job at the International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED) in London to set up the CSE is our most important asset. Anil dreamt of making a huge difference in the way we managed our environment. He brought the perspectives about how people – often poor and often women – were at the centre of the change that needed to be made. He forced us to think differently. But most importantly, he started the CSE. After him, our challenge – my colleagues’ and mine – has been to ensure that the institution continues to be driven by passion and not by the tasks that need to be done. The purpose is important as much as the skill to ensure that it is done with forensic rigour and insight.

This is then the third thread. The fact is that every issue is contested because of conflicts of interest. It is contested because it is the contest of ideas and the contest of realities. To engage in this contest requires research and an ability to stand against the stated truth – or what I have called the established fact. This is where we have faced our biggest enemies. Not because of the conflicts of interest but because of the conflicts of ideas, which is driven by interests.

Read any chapter and you will see what I am talking about. We had to fight the ‘established’ science of diesel in our fight for clean air; the ‘established’ science of pesticides in our work on toxins and food safety; the ‘established’ science of conservation in our effort to bring a new way to manage wildlife so that people also benefit. The list is long. But the war is about the mind.

And as I write this, I am conscious that this war for a space of the mind is only going to become more difficult in the years to come. As I write in “A Blueprint for the Future’, we may believe that the world has become smaller, and we have become more connected, and media has become ‘social’ – but this is far from the truth. In reality, we are living in our individual bubbles, reading who we ‘like’ and un-following those whose views we don’t. Our news of the world has also shrunk, not expanded, and our tolerance for different world views, perspectives or just reality too is shrinking. It should worry us that there is so much that is outside our world and our view now. So many people and so many matters that are earth-shattering, so much grief and so much that needs to be fixed.

And as I write this, I am conscious that this war for a space of the mind is only going to become more difficult in the years to come. As I write in “A Blueprint for the Future’, we may believe that the world has become smaller, and we have become more connected, and media has become ‘social’ – but this is far from the truth. In reality, we are living in our individual bubbles, reading who we ‘like’ and un-following those whose views we don’t. Our news of the world has also shrunk, not expanded, and our tolerance for different world views, perspectives or just reality too is shrinking. It should worry us that there is so much that is outside our world and our view now. So many people and so many matters that are earth-shattering, so much grief and so much that needs to be fixed.

For people like us, who have to push the envelope of the status quo, the going will be tough. But this is where the next challenge will be. We cannot give up; we cannot say let the interests prevail. The conflict is real and it must be contested.

This is the real nub. The fact is that there are two distinct versions of environmentalism – of the rich and of the poor. There is a technical view of the future where machines and automation will smoothen our blips. Then there is the view that unless we develop ways that are more humane and more inclusive we will not be able to build better futures. This is the politics of environment. It cannot be neutered.

Please do read Conflicts of Interest because you must – not only to agree, not only to dissent. But because it tells stories of our present, and points to the common future we must make.

India’s Blueprint

In India, on the one hand there is a greater acceptance of our concerns, but there is also growing resistance against required action and, more importantly, every indicator shows that things on the ground are getting worse. Our rivers are more polluted; there is much more garbage piling up in our cities; the air is getting increasingly toxic; hazardous waste is being dumped and not managed. Worse, people who should have been at the front line of protection are turning against the environment. They see it as a constraint to their local development and ven as they may protest against the pollution of neighbourhood mines, or factories, they have no reason to believe that their livelihood from natural resources is secured. They are caught between the miners and the foresters. In both cases, they lose.

In India, on the one hand there is a greater acceptance of our concerns, but there is also growing resistance against required action and, more importantly, every indicator shows that things on the ground are getting worse. Our rivers are more polluted; there is much more garbage piling up in our cities; the air is getting increasingly toxic; hazardous waste is being dumped and not managed. Worse, people who should have been at the front line of protection are turning against the environment. They see it as a constraint to their local development and ven as they may protest against the pollution of neighbourhood mines, or factories, they have no reason to believe that their livelihood from natural resources is secured. They are caught between the miners and the foresters. In both cases, they lose.

So, I believe, it is time we took stock of developments and future directions.

In the past four decades – the beginnings of India’s environmental movement can be traced to the early 1970’s, when the country saw its first environmental campaign, the Chipko movement, the launch of Project Tiger and enactment of the water pollution law – much has changed. And not yet changed.

The worst indictment is that over 700 million people in India still use dirty, polluting biomass for cooking food and that and equal number defecate in the open. They do not have access to clean water, hygienic toilets that do not end up polluting rivers and groundwater and energy for either lighting or cooking. Clearly, somewhere we are going wrong. Very wrong.

We must also realize that even as the issues have grown, the institutions for the oversight and management of these issues have shrunk. Many actions have been taken but many more actions have come to naught. But most importantly, while the environment constituency has grown – many more people are interested in environmental issues – its core beliefs have gotten lost. In this way, the underlying politics have been neutered.

It is important we point to the fundamental weaknesses and contradictions. It is only then we can deliberate on the directions for the growth of the environmental movement. In my view there are distinct trends that need elaboration:

-

1. We have lost the developmental agenda in environmental management. Instead of working to regenerate natural capital for inclusive growth, we have increasingly framed action as developmental versus environment.

2. As a result, even though the environmental imperative is now better understood, the constituency asking for protection has changed or will change. The management of natural resources – swinging between extraction and conservation – is leaving in its wake millions who live on the resources. Neither the degradation of the resource nor pure conservation helps these people. They need to utilize the natural resource for their livelihood and and economic growth. In this way, the environmental movement is in danger of making enemies of the very people it is trying to protect.

3. The debate on environmental issues is getting increasingly polarized and is seen as an obstructionist one. In this way, the positive agenda gets negated and lost.

4. Environmental struggles are increasingly about not-in-my-backyard. This is understandable as people are the best protectors of the environment and they are saying pollution must not happen in our backyard. But the problem in a highly iniquitous country is that this can simply mean that if we do not want something in our backyard, it moves to someone less powerless.

5. But we must realize that even as middle-class environmentalism will grow, which is important, it will not be enough to bring improvement or change. The reason is that solutions for environmental management require inclusive growth. Otherwise, at best, we will have more ‘gated’ and ‘green’ homes and colonies, but not green neighbourhoods, rivers, cities or country.

6. It is important also then to look for solutions, not just pose problems that do not go away. But this search for technologies and approaches to environmental management will have to recognize the need to do things differently, so that sustainable growth is affordable for all. It also recognizes that new age institutional strengthening is vital – we cannot improve performance without investing in boots on the ground.

7. This demands a new type of environmentalism – one that can move beyond the problems of today and yesterday to embrace ideas without dogma and dogmatism. But for this to happen, it is time we imbibed politics that will make this environmentalism happen.

Before the Flood Full Movie National Geographic

Inclusive growth and sustainable development in climate change era by Sunita Narain

0 thoughts on “Conflicts Of Interest”